It's 1864, and a young boy named Will (Ashton Sanders) works with his uncle, Marcus (Keston John), on behalf of a group of bounty hunters, in locating runaway slaves and reporting their whereabouts so that they may be returned to their slaveholders. Will and Marcus, in order to do this, earn the trust of their targets and divert them to an agreed-upon place so the slaves may be taken captive and returned. What makes Will and Marcus so easy to trust is that they themselves are former slaves, operating under the guise of also being on the run. By the time their targets realize they have been had, they are already back in chains. On one particular assignment, the pair are tasked with locating a freed slave named Nate (Tishuan Scott) in order to return him, but after locating him, Will soon finds himself gravitating toward this perfect stranger, coming to first confide in and then depend on him in a way that the fatherless boy had never experienced. During their perilous time in the wilderness, Nate saves the boy's life, and then later, Will saves his, elevating their bond to staggering new heights. Soon Will's task comes into conflict with how he feels toward Nate and he finds that he must face a very difficult choice.

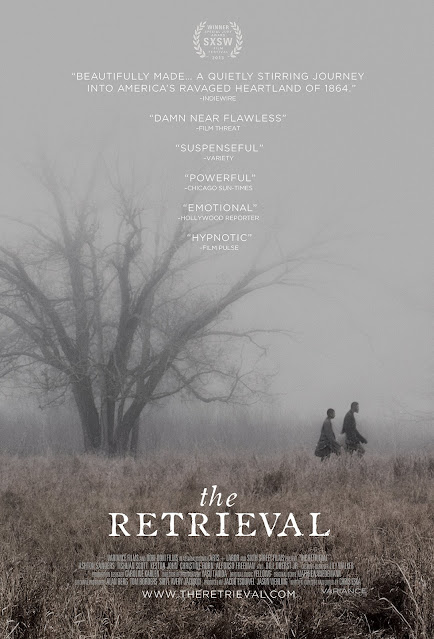

In an interview with journalist Matt Fagerholm for RogerEbert.com, actor Tishuan Scott (who plays Nate) expressed a "dislike of history" in his youth, citing that African-American culture had been too easily summarized merely by the efforts of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Rosa Parks. In his eyes, exactly one hundred years between 1863's Emancipation Proclamation and 1963's civil rights movements was missing from the history books relating to the African-American experience. It has only become recent that tales of the African-American struggle, from the brutally honest with Steve McQueen's 12 Years a Slave to the satiric and exploitative with Quentin Tarantino's Django Unchained to HBO's recent Lovecraftian/Jim Crow mash-up Lovecraft Country, are finally being told. Released within the shadow of 12 Years a Slave lies the little seen film The Retrieval, a story told not just from the African-American experience, but one that sidesteps more obvious approaches in favor of offering an extremely unique and uplifting story. It's also highly superior to those two prominent titles.

Though The Retrieval is not based on any specific event, the film is still firmly entrenched in a very real history. The characters of Will and Nate may have never met, bonded, and parted under extremely emotional circumstances, but the idea of former slaves being forced to root out their fellow man (and being paid to do so) sadly sounds like the kind of additionally awful thing that would be occurring within an already awful and very turbulent period in history. Nearly unfolding in real time, The Retrieval offers up suspense from the very first minute that Will and Marcus cross paths with Nate. Those bounty hunters for hire know exactly what they have been tasked to do, as does the audience, who also knows that this is something they have already done, and are willing to do again. As Will and Nate begin to grow closer, the former yearning for a father he never knew and the latter mourning for his deceased child, the bond that forms between them is as equally heartfelt and satisfying as it is heartbreaking, because the audience knows there new friendship can only end in one of two ways: either Will and Marcus risk their lives in letting Nate remain free, or Nate will end up back in shackles following their many shared campfires in which their greatest fears and regrets were shared and a mutual understanding and respect was forged.

An intimate story propelled by only a handful of performances, it's easy to see why Scott's performance as Nate has been as celebrated and awarded as it was. Same goes for Sanders as the young Will; at no point do either of their performances come off as disingenuous or self-aware. Noted horror/cult actor Bill Oberst Jr., who plays a minor role as Burrell, one of the bounty hunters, also offers strong work. The easy way out would have been to present Burrell as obviously vicious - the archetypal evil white man - but instead Burrell comes across as sympathetic, and even caring where Will is concerned, but this calm demeanor is not to be trusted. He is on assignment just as Will and Marcus are on assignment, and his ideology isn't the thing that's driving him. Ultimately what he has been tasked to do, and what he has tasked Will and Marcus to do, is evil, but to him there's no evil in it. In his mind, he believes what he's doing is just, and the money he is being paid serves as affirmation.

The Retrieval is an uplifting story set during an ugly time, and to echo Scott's thoughts, the world, and this country especially, needs to immerse itself in the history that it has gotten too used to denying, because however ugly and humiliating that history may be, it also contains a plethora of untold stories that need to be told - not just to confront this history, but to gleam from it any saving graces in which the human spirit was not just preserved, but flourished, even in the most dire of circumstances.

Considering this is filmmaker Chris Eska's second film, and shot solely in exteriors using available light, the film is consistently confidently captured – one that deviates between night and day, lit only by campfires, torches, and the southern sun. Whether by design or by happy accident, background shots looked to have their colors muted, so much that at times the sky looks like a faded photograph. Same goes for fields of wheat and dead grass, which alternate from amber brown to stark white. All of the film takes place in the great outdoors, and in the midst of war, so rippling rivers, pelting rain, blowing wind, and the distant cannon fire trickle out through. The pretty musical score by composer Matthew Wiedemann and Yellow 6 alternates between commanding the screen's use of natural landscapes and lying under the surface to complement the more emotional actions and exchanges.

Critics and audiences spent most of 2014 being enamored by 12 Years a Slave - and rightfully so - but one wonders if that were maybe at the expense of The Retrieval, a film that was sadly little seen outside of film festivals. Though both films are set in the same places and during the same times, their stories are told in vastly different ways. 12 Years a Slave is an extremely powerful piece of filmmaking, but it doesn't share the uniqueness of the story to which The Retrieval can lay claim. Far less brutal and far more hopeful, The Retrieval is a celebration of the human spirit and one's own belief in the bigger picture. Flesh expires; hope does not.