“There’s evil on this island. An evil that won’t let us get away. An evil that sends out an inhuman, diabolic power. I sense its vibrations now. The vibrations are an intense horror. It will destroy us! The very same way it did all the others!”

“SHUT UP, CAROL."

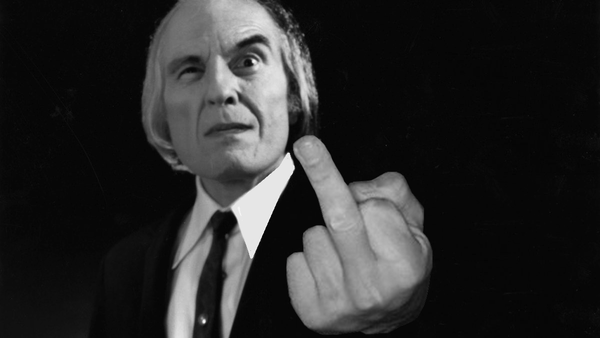

Italian filmmaker Aristide Massaccesi is more commonly known as Joe D’Amato, the most prominent of his many pseudonyms. Like his colleagues Dario Argento, Lucio Fulci, Michele Soavi, Bruno Mattei, Ruggero Deodato, Umberto Lenzi, and the Bavas — Mario and Lamberto — D’Amato was a director and producer primarily known for gross-out, gory horror that featured the kind of gags you’d never seen during the same era of American filmmaking. I guess it’s because Italians are inherently fucked up (I’m allowed to say that), but even during the video nasty era of Britain, or when Reagan et al. were cracking down on R-rated movies and profane lyrics in music, Italian filmmakers were also pushing back on violence and gore — but in the opposite direction. They pushed violence and gore to the breaking point — beyond “this is fun!” to “I’d like to vomit!” D’Amato was the hardest working one among his colleagues, averaging FIVE feature films a year; he directed EIGHT in 1981 alone. (To put things in perspective, similarly “boundary-pushing” horror director Eli Roth has been making features for 16 years and he currently has only seven features to his name, which is a mercy.) By the time of his death at 62 years old, D’Amato had 197 directorial credits. Granted, a lot of this was porn, but hey, a movie’s a movie. (Top title goes to Robin Hood: Thief of Wives.)

1980’s Anthropophagous (aka The Grim Reaper) is one of D’Amato’s most famous efforts, which would be one of several collaborations with actor/screenwriter Luigi Montefiori (pseudonym George Eastman), who wrote Anthropophagous and its sequel, Absurd, while also playing the maniacal cannibal/killer in each. Anthropophagous was one of many titles infamously included on Britain’s official Video Nasty list, which declared this and films of its ilk illegal and was pulled from video store shelves. I won’t go as far as calling it “tame by today’s standards,” which is a go-to line for retrospectives on once-infamous films, but it’s not a constant collection of gross-out gore, either. For much of its running time, it unfolds as your fairly typical slasher flick: a group of attractive youngins go where they ought not to have gone and run afoul of a cannibalistic madman who begins to kill and semi-eat them one by one.

At film’s end, the villainous Man Eater suffers a fatal blow to his stomach, out of which flow his intestines, which he promptly sticks in his mouth and begins to eat as he stares into the eyes of the man who wounded him, which is the greatest spite-suicide I’ve ever seen.

Sure, Anthropophagous is definitely gross, and its infamous fetus-eating scene is one of the grossest things from this genre, but it’s also more well made than you might expect based on its reputation. For much of the first half, in spite of the intermittent murder scenes, D’Amato is much more interested in creating tension and setting a mysterious and creepy mood. A night-brought storm rages, dumping buckets of rain on the crumbling structure where the friends are hunkering down and filling its darkened rooms with blazes of lightning flashes. He also sticks Eastman’s killer, Man Eater, in dark corners and other faraway places nearly offscreen, revealing him in small bursts like a bearded Michael Myers. Reputation aside, D’Amato was a competent director, and it’s to his credit that he was able to work in every genre beyond horror, and especially beyond gross-out horror, even if the horror genre would come to define his legacy. (Eastman, who never minced words regarding his work or the work of others, called Anthropophagous, a film he wrote and starred in, “shit.”)

A soft sequel to Anthropophagous, called Absurd, followed just one year and ten more D’Amato-directed films later, and traveled much of the same path, although this time, Eastman’s script borrowed heavily from the first two Halloween films: Eastman, this time given the name Mikos Stenopolis, is your de facto Michael Myers; Edward Purdom (from the legendary slasher flick Pieces), though his trench coat may be black, is the regretful Sam Loomis; and young bedridden Katia is doomed to act as the film’s beleaguered Laurie Strode. There’s even a subplot of a babysitter watching two kids while the parents fuck off to a party, both of whom having to contend with a killer in their house. (The babysitter, however, isn’t so lucky this time.)

The reason I call Absurd a soft sequel to Anthropophagous is because it doesn’t feature any returning cast members beyond Eastman, and even then he’s playing a brand new character that's also basically the same as his previous Man Eater. The film also finds a way during its opening scene to replicate the fatal wound that Eastman’s Man Eater is dealt in the final moments of Anthropophagous in an additional effort to tie the films together. However, Absurd isn’t nearly as successful as its predecessor, surrendering to a more common and less interesting setting and falling back on a less assured pace. In Anthropophagous, tension built from having our characters wander a desolate location where we know the killer to be and slowly put together the events of the dastardly deeds that have gone down there. In Absurd, we spend way too much time watching a bunch of middle-aged party-goers standing around watching American football on TV and eating spaghetti. That sounds like I’m making a joke, but I’m not — that’s really what happens. (Spaghet!) Obsession with American football must’ve been at an all-time high in ‘81 because every character beyond Eastman (who never speaks) mentions football at least once. Like Antropophagus, the murder sequences in Absurd are top notch, but they all occur so far from each other that we’re forced to spend most of our time with the police investigation side of things, led by Sgt. Ben Engleman (Charles Borromel, who looks freakily like Robin Williams).

Interestingly, though Absurd seems to borrow heavily from the plot of Halloween, both Absurd and Halloween 2 were released in October of 1981, and both feature a finale in which the maniacal killer is blinded and the final girl begins throwing off the path of the coming killer by creating false signs of her presence around the room using anything that makes noise, allowing for someone else to come in and dispatch the killer. The very ending even predicts that of Halloween 4, which wouldn’t be released for seven more years, so apparently Eastman piped into some kind of wormhole that allowed him a glimpse of the next decade of official Halloween canon.

Fans of Italian horror should see each title at least once. I wouldn’t go as far to call them cult classics, but they do feel like necessary viewing for those who have a predisposition toward “extreme” Italian horror cinema.

|