Remember that one time you went on vacation with your family to Tombstone, Arizona, or Dodge City, Kansas, and just after finishing your "Buffalo Bill Burger Blast" you went outside and caught the noontime showdown in the street between those two guys in the really bad beards shooting each other with blank pistols whose gunfire seemed to be coming out of the crackling speakers behind you instead of the deadly instruments grasped in their hands?

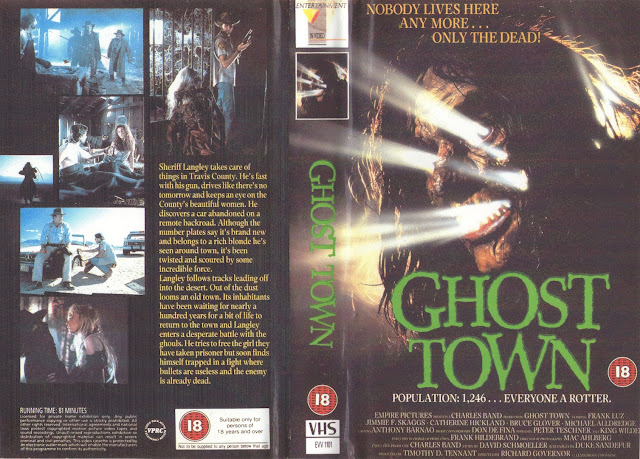

That's Ghost Town, in a nutshell, with costume store make-up. It is glorified dinner theater with a horror bent and a budget slightly higher than the one possessed by those people who put a little too much effort into their front lawn Halloween displays. And of course, there's obviously nothing wrong with this, because Ghost Town, despite its obviously low budget, its lack of anyone with name recognition (beyond Bruce Glover), and its somewhat restrained use of visual effects (how many times "ghosts" disappear/reappear on screen after a while becomes hilarious), remains an infinitely watchable film, perfect for those late nights when you don't want to surrender to sleep just yet, but you don't want to watch anything heavy. It's Ghost Town, all the way.

What's refreshing about Ghost Town (and unlike many other Charles Band productions) is that everyone on screen knows they're making something silly, yet everyone is sincerely giving it their all. Not every performance is Day-Lewis caliber, but obviously that doesn't matter, because even though the film revolves around a hapless deputy wandering into a ghost town in the middle of the desert and stumbling upon a collection of ghosts, skeletons, and people trapped in time, every member of the cast does admirable work, including the Michael Bay lookalike lead character of Langley, played by Franc Luz.

With a typically quirky story by, at one time, go-to Full Moon Pictures auteur David Schmoeller (interviews with him here and here), Ghost Town is charmingly innocent and not the least bit pretentious. Band became a producer infamous for not only low budget horror, but low budget trash horror, which has only gotten worse over the years, so to see his name affiliated with a project built on good intentions of just trying to tell an old fashioned story is not only surprising but welcoming. Except for the icky ghost make-up exhibited by some of the on-screen ghouls, and a few moments of bullet carnage, Ghost Town isn't terribly violent, either. (It also exhibits the most restrained and tasteful allusion to ghost rape probably ever.) Its tone goes for serious but light at the same time, and except for a moment of side-boob, Ghost Town feels like something to put on for the kids on Halloween night.

Ghost Town's "rules" get a little fuzzy as the film progresses: sometimes the characters Langley encounters are ghosts, sometimes living skeletons, and sometimes living folks (?) "trapped in time," and after a while it's hard to figure out what exactly is going on, and who is in danger of what (apparently those trapped in time can still die - again, or for the first time), but Ghost Town's intentions are pure enough that after a while none of this really matters. There's no denying that the film is patently stupid, but that's okay, because the amount of love that went into this production evens out its inherent stupidity, resulting in a good time.

Ghost Town is deliciously, lovingly, charmingly, and acceptably stupid. It's the perfect example of a title that would have fallen into obscurity in the years following its release just because of how odd, quirky, and somewhat kid-like it is...and let's not forget those visual tricks on the same level of a ghostly Unsolved Mysteries episode.