Part One of Franchise Regeneration explored the entire history of the

Universal Soldier franchise, breaking down its wacky, wacky path, but it mostly examined the two newest entries,

Regeneration and

Day of Reckoning, directed by filmmaker John Hyams. Taking a series of increasingly silly films that had gone way off the rails, Hyams reinvented the characters and concepts established in Roland Emmerich’s 1992 original film, starring Jean-Claude Van Damme and Dolph Lundgren, and implanted them in a post-

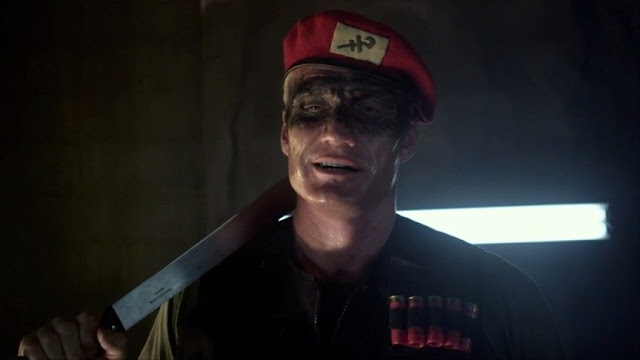

Batman Begins world where action films dropped the humor and puns and embraced the darkness. No longer does Lundgren’s Andrew Scott wear a necklace of ears and demand to know if you can “hear” what he is saying. In this new world of

Universal Soldier 2.0, he instead looks haunted and sad – in the midst of an existential crisis. He no longer wants to crack jokes as he cracks necks; instead, he wants to know how often you “contemplate the complexities of life.” And Van Damme’s Luc Deveraux isn’t the man of hope that the 1992 original film wanted to suggest at its conclusion. Instead he lives a ruined life; on the fringe of humanity, lost within himself. What the new millennium

Universal Soldier has come to mean is in stark contrast with what it once did back in the early ’90s.

In the below less-of-an-interview-and-more-of-a-conversation, Mr. Hyams talks about his start in documentary film, how he landed the gig of directing Universal Soldier: Regeneration, his love for John Carpenter, his optimism over Neill Blomkamp’s Alien 5, the importance of exploring new ideas, and what the future holds for the Universal Soldier franchise.

Q: Having worked in documentaries, feature films, and television, what is your first love as a director?

Hyams: My first love as a director is feature films, without question. I love the process of feature filmmaking because you can focus on one idea and prep that one idea and shoot that one idea and then spend a good long time in post-production on that one idea. I feel like, on the making end of it, there’s nothing more satisfying than being able to immerse yourself in and focus on one particular thing. I feel like that’s what I’m best at.

But I’m definitely taking a greater interest in television, because I’m seeing that the kind of stories I’m interested in telling are being told much more in television than they are in feature films. That’s why I specifically wanted to get involved with television: so I could start trying to explore my own ideas. Having said that, television is like sprinting a marathon. It’s a harried experience. I’m a producer, director, and writer on the show I’m working on now [

Z Nation]. I’m not the show-runner, but I would love the experience of being a show-runner. What I’m learning, and what I learned about in my past experience in TV, is being a show-runner is really the art of delegation. It’s the art of directing and writing through other people. It’s an amazing art form in and of itself, but when you’re a feature film director, you’re sort of encouraged to micromanage. It’s part of what you do because you need to be on top of all the details. That is something where, when it comes to TV. Look at Vince Gilligan [creator of

Breaking Bad]. He is probably still a micro-manager, but he knows when to step in. You don’t step in too early in the process. These are all things I’m learning about.

Hyams: As for documentaries, there was something incredibly satisfying about the idea of stripping down the mechanism of it all. It doesn’t require a crew, or so much negotiation. That being said, when you’re making a documentary, the process of editing is the process of writing as well, not to mention the process of shot collection and performance. You’re really searching for the narrative. A documentary is kind of a long game where you’re shooting stuff, cutting stuff, showing it to people and getting more ideas – shooting and cutting, shooting and cutting. That was an enjoyable process when I was doing it because I was in sync with the people I was doing it with. It was just a few of us. It was kind of like being in a band, if you know what I’m saying. It was four guys on the road, in hotel rooms, and a few people in the editing room. And like bands, it’s ripe for personality conflict. So at a certain point, there’s only so long where you can keep the band together. I certainly have an interest in doing documentaries going forward, but this time doing them in a very different way, again, where I would be much more of a delegator and someone who is kind of helping shape the thing, but through other editors. I learned how to edit from editing documentaries, but I don’t have an interest in spending 18 months in a room by myself going through six hundred hours of footage. There are other things I want to do creatively and I don’t love that enough to devote myself fully to that.

I love the pace and life of a feature film. I come from the arts – I was a painter and sculptor, so that’s really what I studied and what I did professionally before I did this, so that’s how my creative process worked. While I was a painter, I got involved in film because I craved collaboration and I wanted to work with other people and create something that took a lot of people to erect, like a piece of architecture, which is what a movie is. But, again, when I get through the shooting process, there’s nothing I love more than to be totally alone with it in the editing room. And I think that’s why I edit my own things: it brings me back to being alone in a painting studio and working through my ideas by myself because that solitary experience is where my best ideas come from. I love the collaboration, but I like to bring it back to that solitary experience. In TV, there’s very little of that solitary experience. Maybe I will get to a point where there will be more of it when I’m more in charge, but right now it’s much more about managing personalities and being able to work with people. It’s kind of interesting: on one hand I love the collaboration where you’re able to pull upon the talents of so many people – whatever your idea, it’s constantly improved by the people you’re working with – but I also love the part where I can disappear into a room by myself for twelve weeks and work my way through something.

That’s kind of a long-winded answer, but they all have things about them that I love.

Q: A good documentary filmmaker has the ability to explore very disparate topics. The two documentaries that I wanted to talk to you about were The Smashing Machine, which is about mixed martial arts, and Rank, which is about bull riding. Except for the fact that they both fall under the umbrella of sporting events, they’re incredibly different subjects. How did you get involved with both of them? Were they ideas you wanted to explore, or were the ideas brought to you?

Hyams: In neither case did I generate the kernel of the idea.

The Smashing Machine was something that was brought to me by the producer of the documentary [Jon Greenhalgh], whom I had known. He was friends with Mark Kerr, the [documentary’s] subject – they had been wrestling teammates in college. I had been aware of Mark through following a little bit of his UFC career via John. UFC was in its infancy at the time, but it was something that was interesting to me. At the time I had no interest in documentaries, but when he came to me and said, “I know this guy, Mark Kerr. He’s a very honest guy and he’s at the top of this sport,” which was not that big in the United States but very big overseas. I thought of this as an opportunity to bring a narrative feature film structure to a documentary. I thought of

Pumping Iron, where you had a story that was moving through time rather than being retrospective, and I loved the idea that you could use this competition as a narrative framework that would basically be a way to enter into a subculture and learn about these “characters.” So my thought was, if you learn about the characters, you’d begin to care about the characters, whomever they are. So, if you cared about them, and when you put them into a competition – a violent competition – you’re going to have built-in suspense and tension. That right there, as an idea, sounded interesting to me. It felt like an opportunity to tell a story that would be suspenseful and draw in the audience.

Hyams:

Rank was created after doing

The Smashing Machine. IFC approached us about doing a documentary with them. At the time we actually had an idea that would be a competition-based documentary series. Each episode would be about a different venture and subculture, and bull riding was the first idea we came up with.

Q: The theme of competition is an excellent idea to have for a factual-based show, in that it delves into different things with each episode. So I take it that led to Rank, but ultimately Rank became its own thing?

Hyam: That’s right. I always thought it was a great idea. We pitched it to ESPN right around the time they began doing 30 for 30. We actually pitched that idea to every network and no one bought into it, and I think that’s because everyone at that time was stuck in the model of needing to have…they think in terms of reality TV, so you need to have “characters” that carry over from one episode to the next. Everyone’s more interested in doing, you know, whatever – Orange County Choppers – than a series that has a different set of characters each week. I thought it was a great idea: the common thread was competition, and the common thread is you follow a different set of characters through competition, which gives you the narrative framework in each episode. And through that you learn about the characters. But, nobody bit.

Q: It seems like by the time Rank was released, so many of these networks – like Discovery and the History Channel – had sort of sold their souls to the reality television movement, and even though they tried to lend some of their shows some kind of educational aspect, they just got to be really void of the kind of programming for which they used to be known.

Hyams: It’s because “reality TV” is just another word for “producer-driven documentary.” What that means is when you make a documentary, you cannot force the action, and reality TV is predicated on forcing and manipulating the action, because it’s cheaper and you can do it quickly. Producers fell in love with the idea of creating a narrative and conflict but calling it non-fiction, even though it’s fictional. All reality TV is fictional. I have friends who work on shows – I won’t name the shows – but you wouldn’t believe it. It’s not that some of the facts are fudged, it’s that every single thing you’re seeing isn’t true. Any side character is a hired actor. The producers decided, “Hey, it’s basically fiction with non-union actors and no writers. And it’s cheap.” So that’s how it went. What we were proposing was a documentary series. Again, the reason why our idea worked, it would’ve been…

Rank was about a contained time period. It was taking a two-week event as a window into a subculture. In the case of

Rank, it was the subculture of cowboys. It would’ve been a very contained shooting schedule. You don’t get the degree of intimacy that you did in

The Smashing Machine by spending a year with someone, but you do get a nice glimpse into these characters, and the competition itself is what pulls you through the narrative.

Q: Switching gears to your feature films, I want to talk about your first Universal Soldier movie. Once the studio showed interest in making another entry in the series that was fated to go direct-to-video, how did the opportunity cross your path? Did you lobby for it, or did someone offer it to you?

Hyams: It kind of fell in my lap. I had been doing some work for the producer, Moshe Diamant – some storyboard work – and he was familiar with my documentary work. I’d done episodic TV during that time; I’d worked on the show NYPD Blue for a while as a director and producer, and I really wanted to get into features. [Moshe] at one point sent me the script, which was quite different from the finished product, but it had the same general premise: about a kidnapping in Chernobyl. The long and short of it was: if they could get the two stars – that would be Jean-Claude Van Damme and Dolph Lundgren – to agree to appear in the movie, then the movie could get made. The problem was both Van Damme and Lundgren had rejected the script and had said no to whatever past directors had been put before them. I think the producer’s thinking, which was correct, was that I had a leg-up because my dad [filmmaker Peter Hyams] had worked with Van Damme on really his most successful ventures [Timecop and Sudden Death], artistically. I think the belief was that would help my standing in his eyes, which I’m sure it did. Then it was basically my job to take that script and change it in order to not only make a movie that I felt would be something to help my career and not hurt it, but also that would get those two guys to agree to be in it.

It was really a crash course in how movies get made: you have to appeal to the stars who have the clout to get it made, you have to do script changes that are going to change the direction of the story that they want it to go in, you have to make sure that that’s a direction you, yourself, are comfortable with and something you feel you can execute well, and you also have to please the producers and the studio and everyone else in that process. That one movie kind of taught me the process of trying to make a film. Even though it happened very quickly, it taught me almost everything I needed to know moving forward from that point on as to what it takes to get a movie made. There are movies I have spent years trying to get made, but on that one, the script was sent to me in September of 2008, I was in Bulgaria by November, and we were shooting by January. So, some things that do manage to get made come together very quickly.

Q: Obviously your father had worked with Van Damme twice before up to that point, and he served as Director of Photography on Regeneration. How instrumental was he in bringing you all together? (I rewrote this question something like thirty times to avoid making it sound like I was implying you got the gig because you were the boss’ son.)

Hyams: But that’s true, actually. That’s exactly why. He was very instrumental and I wouldn’t have gotten the job if it weren’t for him, because those guys wouldn’t have had the confidence in me. He was the reason, though it was less my father being the catalyst for it and more the producer, Moshe Diamant, who knew that was the way he could get it done. I think the way it actually went down was that Moshe offered it to my dad. Moshe needed this movie to get made, for whatever reason. It was a film that was very close to getting greenlit. I think he went and offered it to my dad and my dad had no interest in doing Part 3 of Universal Soldier. But my dad offered to serve as the DP if it would help get the movie made. So they had another director in mind at the time, and my dad was going to DP the movie as a favor to Moshe, and when it didn’t work out with that particular director, then my name came up – whether my dad suggested it, or Moshe suggested it, I’m not sure. But I’m sure my dad was all for trying to get me the opportunity, and once that came up I used that to the fullest.

I certainly had been out there plugging away in this business doing the documentary work and indie film work, making shorts, doing network television work, and once you spend some time trying to work in this business, you remove your ego from the situation. If an actor decides to work with me because I’m Peter Hyams’ son, that’s fantastic, I’ll take it. In the end, it’s me who has to sit there and make the movie, and edit the movie, and score the movie. It still all fell on me. It’s kind of like…if a beautiful girl wants to date you, you don’t ask her why.

Q: [laughs] Right.

Hyams: Look, it’s really hard to get a movie made. The bottom line is: actors need to trust the director. Whatever it is that helps them trust you, especially if they don’t know you at all, you need that. Sometimes it’s a producer who’s involved and whom the actors trust, and so they trust you by association. In this case it was the DP, and I took it.

Q: You mentioned that Van Damme and Lundgren had both rejected the first draft of the script, and some time after that, you went and met with them and described your approach to the characters. Even though you didn’t get any screenplay credit, did you perform any drastic rewrites?

Hyams: I did. I did quite a bit of rewriting on that. I wasn’t interested in credit. I should say that some of those rewrites were actually done with another writer named Gene Quintano (Sudden Death), so I oversaw those rewrites with him and those were the main rewrites. And then I did a final director’s polish. I had never even met the original writer [Victor Ostrovsky] because he was just long gone from the situation by then. I don’t know how long the script had been out banging around. But that stuff needed to get done and we were on a very tight schedule. I met with Jean-Claude – I flew out to Brussels and met with him – and then I met with Dolph. Both he and Van Damme were not only not interested in the script, but I think they were very reluctant to enter into what they thought would be a bad movie. They thought it was under-budgeted – they had experience working on things like that, which didn’t go well for them – so they had a lot of hesitation, and I think it was probably well-founded hesitation.

I remember having a meeting with Dolph at Millennium Films, because he had a relationship with those guys. They were producing a movie at the time that Dolph was directing – I think it was Command Performance. So, by meeting him there, it gave the feeling that Millennium was on our side. I pitched to Dolph what my ideas were for his character, and mind you, I had only just recently read the script before all this, so for a lot of it I was flying by the seat of my pants. It was kind of, in general, what my ideas were for his character, which was completely different from what was in that script. I had come up with a completely different idea for his character that I hadn’t fully worked out in my mind. I hadn’t done a rewrite yet. I remember him sitting in the meeting and saying, “I like what you’re talking about, but I would have to see the pages.” And I said, “Okay, I could have a rewrite done in the next three to four weeks.” And he said, “Well, I’m only in town for another three days,” or something like that. And I said, “Well, okay, I can email it to you.” And I remember during the meeting [laughs], some of the producers said, “Well, why don’t you write his scenes first?” And I said, “Well, I’m not exactly sure where they happen in the story,” and Dolph said, “Yeah, that would be good if you wrote those first.” So I went and wrote his scenes, which are the exact scenes as they happen in the movie. I wrote those before I even knew where they happened in the story.

Q: [laughs] Oh man…

Hyams: Yeah! So I just sat down, wrote those scenes and sent them to him, and he agreed. So, that kind of shows you how that went down.

Q: Not to blow smoke up your ass, but after hearing about all these behind-the-scenes complications and the condition of the original script when you first signed on, Regeneration is a fantastic film. I think you did a great job, especially for it being your first feature.

Hyams: Well, thank you. I appreciate that.

Q: The action is incredible and so different, and I absolutely love this new approach to these old characters, who had been lovingly established in that early part of the 1990s where the action was still over the top, but the characters were so silly, and everything was about puns and trying to end every scene with a laugh, and Van Damme is walking around outside with no clothes on. And then you take that concept and you implant it into this new environment where everything is cold and unforgiving and brutally serious – it was a wonderful, really risky decision that totally paid off.

Hyams: I really appreciate that. That was basically the pitch, what you’re saying: I was going to take it completely serious. You know, how do we use that essence of the

Universal Soldier concept? I had to discover for myself what it was about that concept that I liked, because I wasn’t necessarily a fan even of the original. So I said, “What’s my ‘in’ to this?” And I chose the kind of sci-fi/horror aspect, the “Frankenstein” aspect. By focusing on that, that’s what interested me: “what if we treat it like sci-fi action/horror? And what if we try to take the existing basic mythology, but then write the mythology where it serves this idea that we are actually trying to take this seriously and make a good thriller and not rely on the gags?” Because, quite frankly, that wasn’t my interest or aesthetic. So for better or worse, that was kind of the way I pitched it and that was, I guess, enough of what those guys were interested in. If nothing else, I could use, in the language of my pitch, “Well, I come from documentaries, so I want to bring” – even though it’s not shot like a documentary at all – “that kind of presentation,” which Jean-Claude really responded to. I wanted to bring that type of honesty and realism to the characters. I don’t think it’s a realistic movie, but we tried to take the mythology as seriously as we could, even though the mythology was created in the beginning for comedic purposes; that was a challenge, but it was a fun challenge. There are things that are funny and silly about that, but you could also say the same thing about

Alien, right?

Alien, at its heart, is a Roger Corman B-movie that Ridley Scott took incredibly serious. And

Alien’s one of my favorite movies – of all time. Or a better example is probably

The Terminator, which is probably a closer relative.

The Terminator always had that kind of Arnold humor, but it was a dark, R-rated, good-ol’, violent, bad-ass, serious movie and it took itself just seriously enough that it felt like the stakes were real.

Q: And that makes total sense. The Terminator is basically John Carpenter’s Halloween with time travel. Mechanically it’s the same exact story, but approached in two very different ways – one as brutal, future-punk, sci-fi action, and the other just funhouse scares.

Hyams: And there you go. I come at all this, ever since I was a kid, as the biggest Carpenter fan. I love Carpenter. My brother and I, outside of being influenced by our dad’s films, and films by Scorsese, Coppola, Kubrick, were huge Carpenter fans. He had the ability – especially with Escape from New York and The Thing, which are my favorite movies of his, but even going back to Assault on Precinct 13 – to tell these kinds of edgy stories that had one foot in the grindhouse world, but which weren’t campy. He took it all seriously and had established a tone that was sort of anti-establishment that I really responded to as a kid. Making Regeneration, I thought about him a lot – certainly when it came time to scoring the movie; we were thinking about two things: Tangerine Dream and Carpenter.

Q: And you definitely hear that in the score, too, and that’s something else I was going to ask you, but we’ll get to that once we start talking about post-production. But that Carpenter aesthetic comes across. He’s my favorite filmmaker – living or dead – and I celebrate every one of his films, even the ones that most people would consider to be the duds. My favorite is probably The Fog.

Hyams: The Fog is fantastic.

Q: I recognize that The Fog isn’t his best film or his most polished film, but there’s something about the atmosphere he creates in that, and the music, it really establishes an effective tone. I can watch The Fog over and over, and let’s face it: I do. Every April 21st, I pop that sucker on, like a big dork.

Hyams: [laughs] Nice. I love it and I’m with you. He’s one of my biggest heroes in the world next to my dad.

Q: You’ve worked with Van Damme three times so far as a director (including Dragon Eyes), and you’ve also worked with him indirectly on your father’s film, Enemies Closer, where you served as editor. And over the years, because of your father’s relationship with him, I’m sure you met with him informally. By now, how would you describe your working relationship with him? He seems to really trust your creativity and he seems willing to go with you on your more riskier directions.

Hyams: Well, you know, to your first point, I had never actually met him prior to doing Regeneration.

Q: That’s pretty surprising.

Hyams: Yeah, because when my dad was doing

Timecop, I was away at school. Same for

Sudden Death – I was not around for those shoots.

Q: Did it kill you to be stuck away at school while your father was making action movies with Van Damme? Because that would’ve killed me.

Hyams: [laughs] Well, you know, I grew up hanging out on his film sets, and, to be honest, I was much more interested in what my dad was doing rather than Van Damme or any other performer. I wasn’t even necessarily such a Van Damme fan because I was less interested in martial arts and more interested in things like, you know, Carpenter movies, or sci-fi movies – just any movie, really. I love all movies; I love Woody Allen movies – he’s one of my top-five favorite directors. I’ve always been interested in filmmakers. Those are the people I follow. I go see a movie not because of the performers who are in it, but because of the director who made it. That’s 100% my criteria for any movie.

Q: That’s how you know you’re a film geek: when you choose to see a film because of the filmmaker, not because of who’s in it.

Hyams: Exactly. And there are actors that I love, but it’s all about the director. Those are the stars to me. To your second point, I developed my working relationship with Jean-Claude on Regeneration, and as it turned out, he became a part of my other movies that I was making, and he had to okay me as director for those movies, or else I wouldn’t have gotten the jobs. He obviously had enough trust and was happy with whatever we did. After Regeneration, I spoke to him and he was happy with it. But the reality of it is my only interaction with him has been on movie sets or on location. I’ve never seen him outside of that and never socialized with him or even been in any kind of contact with him beyond the movies. And that probably goes for most of the actors I’ve worked with in movies. I have a lot of friends who are actors and some have played parts in my movies, but with Jean-Claude, his decisions to be in those movies were all happening from afar. He’s either in Hong Kong or Belgium or wherever he’s been. Regeneration was the longest shoot I’ve had with him; on Dragon Eyes I think I shot with him for two days, and on Day of Reckoning he shot for five days.

So, yeah, I think we have a good working relationship. I know how he likes to work, and it took working with him to understand that, so by the time I got to Day of Reckoning, I really tried to tailor-fit the character to him – to ensure that it would be different from what we had done together, and [to heighten] what I think is interesting about him.

Jean-Claude had his day as an action star, but what I see him doing now, really successfully – recently even – is that he’s a really interesting character actor now. Now that he’s older, he brings a different energy and a different persona. He’s not the young guy doing the splits anymore – Volvo commercial aside, and that was hilarious. Just like the movie he was in, JCVD, and even what my dad did with him on Enemies Closer, are other kinds of examples of different, interesting performances that he can bring. He has this really different kind of extreme energy, and he doesn’t always have to play the hero. Sometimes he’s more interested in playing the antagonist, and he’s even showing he can do comedy now – like that film Welcome to the Jungle. So I think that’s what I was looking for from him, and it was less about what we wanted to do with him and more about not wanting to make the same movie again. I was really trying to think, “What’s a completely different approach we can take to this material?” We had made Regeneration, and I think we made that as well as we could have given the context, and there was no reason to repeat it. So that’s what Day of Reckoning was born out of.

Q: Getting back to what you said earlier: in my kind of ridiculous dissertation that I wrote on the Universal Soldier series, especially your two entries, I praised Van Damme for this kind of career 2.0 that he’s established during his later years. A lot of these guys, like Dolph and Seagal and these other guys who were in the action spotlight in the late ‘80s/early ‘90s – whose schtick it was decided wasn’t needed anymore – have all ended up direct-to-video in these less than stellar movies. But Van Damme has consistently made the most interesting choices and has really taken into consideration his projects before he signs on. If you can get over the stigma that these things go right to video, or they open in maybe 100 theaters across the world, his newer films, like your two Universal Soldier entries, Assassination Games, Wake of Death, are actually better by and large than some of the stuff he did in the late ‘90s that ended up in theaters.

Hyams: That’s a good point, and you’re right. After getting to know him, I’ve learned that he’s not afraid to take risks. He’s actually interested in exploring darker characters and he has done that in some of those other movies I’ve seen of his. He’s not just trying to be the same boring heroic character. I think that’s great; it’s his willingness and interest to go to those places that gave me the indication he would be down with doing something like Day of Reckoning, where we took the character in seemingly a completely different direction. But you’re right: he’s courageous that way. And he’s a really interesting person. You know, I really like Jean-Claude a lot. He’s got a lot of heart; he really wears his emotions on his sleeve. And he’s very good to the people he works with – he’s a kind person and well mannered. And he doesn’t have to be. People who are in his position don’t necessarily have to be. But Jean-Claude was always very good to the people who were working on his films, and who were around him. I always responded to that kind of sensitive side of him and his personality. That’s what’s interesting about him.

In

Regeneration, I think the thing that he responded to was the idea of the reluctant gunslinger. We talked about

Unforgiven, you know? Here was a guy who was reluctant to go back and fight, and I think he liked that. And playing to his age rather than deny his age.

Q: It’s funny that you would bring this up because this was literally the next thing in my notes I wanted to talk about: one of the best aspects of Regeneration is that this new iteration of Luc Deveraux isn’t the generic idea of the retired hero an after-the-fact sequel would include. It’s not like he was sitting at home and the U.S. government called and said “We need you Luc!” and he said, “I’ll do it because America!” This guy was asleep in his house with Animal Planet playing on his television when a SWAT team smashed through his windows and all but kidnapped him. Though he makes the choice to shed his humanity and embrace this old version of himself, really, he had no choice at all, and that’s a really interesting concept for an action hero. He’s not doing it for any other reason other than his mind has been completely scrambled over the years and he doesn’t know how to make decisions for himself anymore.

Hyams: Right, and I think that, again, was the fun thing to explore in the story, which was something new that was not in the original script. Even though the original Universal Soldier kind of touched upon that idea, because the original, in its own funny, campy kind of way, was still about post-traumatic stress disorder. So we decided to run with this concept: what if you created a being or monster purely for the purposes of fighting and killing? Logically speaking, that being would basically be depressive in any other state and that the accumulation of violence that this being had been through would be akin to putting a dog into a fight ring. I think some of the original ideas were more along the lines of a jingoist “America, fuck yeah!” concept. When I read the first draft of the script, it was originally that these terrorist separatists kidnapped the prime minister’s children, so they had to thaw out these universal soldiers to save the day, but I couldn’t get past the fact that the crimes of this separatist group were completely dwarfed by these crimes against humanity that the government had perpetrated by creating a slave race of human killers. I decided that the whole kidnapping thing should be a MacGuffin, and that it’s really about the slave race of killers – that at a certain point, and at the end of act two, the crisis will be solved, and yet the inmates will be running the asylum. They’ll have taken care of that external problem, but the real problem is they created warring monsters, and those warring monsters, if they don’t have a war to fight, they’re going to start a war.

Q: And that creates one of those timeless concepts that a lot of films like to posit: who is the real bad guy? That goes all the way back to 1968 with Romero and Night of the Living Dead.

Hyams: Sure,

Night of the Living Dead is a perfect example. And that collage at the end of

Night of the Living Dead is pretty chilling.

Q: I have to ask you: while you were shooting Regeneration with Van Damme, did you ever have any conversations with him about the previous Universal Soldier film he had done, The Return, and what he thought about the final product?

Hyams: I can’t remember if I ever had a conversation with him about it. When the producers hired me, I had never seen The Return or the original Universal Soldier.

In the original script for Regeneration, there were scenes from the first Universal Soldier that they wanted to intercut, so the first thing I said to them was, “Look, that movie came out a long time ago. I, personally, have never seen it. I think it’s important we make a movie that can stand alone. It can harken back to the mythology of the original, but it needs to totally exist on its own two feet.” And they agreed. But I said, “Mythologically speaking, in which of these movies do you feel there is important information?” And they said to just base it off the original, and not [to mine from] The Return. I think they felt that they didn’t quite get it right with The Return. And I said, “Okay, fine.” So I didn’t even watch The Return. I watched the first Universal Soldier, and I got a basic idea of what information was important. And I totally ignored The Return. It wasn’t until I started writing that I went back and started looking at it and realized Luc Deveraux becomes totally human, and I think he has a kid or something. And I thought, well, that’s moved so far away from the initial concept that it’s not worth exploring. It’s one thing if this were The Dark Knight franchise and every movie came out a couple years after the next, but this wasn’t a series that audiences were following, so we needed to reintroduce the idea of Universal Soldier and whatever that means, and whatever that did mean was not a guy who had become completely human.

I don’t know what Jean-Claude even thought of that movie. It was enough for the producers to tell me not to go down that road and I didn’t ask them a second time. I proceeded and ignored it.

Q: I take it you have not seen The Return in its entirety in the years following your having made Regeneration?

Hyams: I kinda have. No disrespect to the makers of the film – it’s not up to me to do that – but I’ve seen enough of it and read enough about it that I got the jist of it and realized it was not a road I wanted to go down.

Q: Well, I have no ties to those filmmakers, so I’ll just tell you: it was awful.

Hyams: [laughs] That seems to be the consensus.

Q: I’m a Van Damme completist and I have to see everything, regardless of its reputation. I had heard it wasn’t great, but I was trying to rationalize, “Well, Van Damme is in it, and Michael Jai White is in it, who is a bad ass—”

Hyams: Yeah, Michael Jai White is great. I have a lot of respect for Michael Jai White.

Q: The first Universal Soldier…it’s silly and there’s a lot of kitsch to it, but they take enough of it seriously so that it’s not a full-blown cartoon. But then, in The Return, you see Deveraux walking around grinning ear-to-ear, and people are making jokes like, “When are you gonna get back in the field, Luc?” and he responds, “Been there, done that!” and it’s—

Hyams: [laughs]

Q: I mean…does no one remember that he died? That he is a dead man? And robot parts are still in his brain?

Hyams: [laughs] That’s the thing: I needed to constantly remind…You can’t get too far away from the fact that this guy is a zombie, so let’s not forget that. And if a movie tries to forget that, it’s kind of getting away from its central idea.

The original

Universal Soldier, like you say, does have a lot of kitsch and it is really funny – the whole popcorn-eating scene – but they make up for it with the intense brutality, and I appreciated that. They still had a lot of crazy violence and Dolph’s character was really dark and so it was good B-movie fun. They ran with their concept. And it was a large-scale movie: they’re at the Hoover Dam and they’re blowing stuff up. It had that scale that Roland Emmerich would become famous for eventually.

Q: The sequence in Regeneration where Deveraux storms the Chernobyl office complex lasts for about 60 seconds, unbroken, which is a pretty great filming achievement, especially considering this was a low budget production dealing with two dozen stunt guys and three times as many squibs and pistons shooting prop paper and debris across the room packed into a really tight shooting space. How much preparation went into shooting this scene?

Hyams: It’s funny: that was originally not supposed to be a “one-er.” When we were prepping for the movie, that was originally going to be covered, and it wasn’t until the day before we shot it…We were shooting all that week, all of the sections of Deveraux storming the complex. There’s a few different stages to it: the first is when he runs through the town square and explosions are going off and he’s shooting everyone and they come after him, and that’s all one stage. And then the second stage is him going through that building. And the third stage is him with the knife.

For the first stage, we had a pretty good idea of how we wanted to shoot it: we were in this big, wide open space, and that was going to be comprised of these wide shots following him in. The third stage was going to be all close-quarters, following him with the knife and stabbing guys. When it came time to shoot the second stage, we were all trying to figure out how we could set that part off and make it different from the other two. And I may have suggested we do it with a lead-in and a following shot, and I think it was my dad who suggested we do it in one shot. And I thought, “Yeah, that’s a great idea.” So once he said that – I’m pretty sure he was the one who suggested it – we then went about rehearsing what the move would be. It kind of changed how the action would play. We thought that would make it interesting – to have a “one-er” sandwiched in between these two stages, and to have one where there were actual, practical effects going off, with the squibs and everything.

We essentially had one day to shoot it, and because of all the set-up, we only had two chances to get it right. For the amount of pre-rigging needed – all the squibs and all that stuff, and if we made it all the way down the hallway, or even halfway down– it was going to take two or three hours to prep it. We did it once, before lunch, and didn’t pull it off. The camera got nudged near the end. And we realized that we had painted ourselves into a corner, so if we couldn’t pull it off with the second take, that sequence just wouldn’t be in the movie. We would’ve just had to skip straight to the third section.

That’s why it becomes kind of a calculated risk when you do those “one-ers,” but fortunately we pulled it off the second time. And it was great. Anytime you do that, you never regret it. You always regret it when you don’t try those things, but whenever you attempt these extended takes, or something that requires choreography, everyone involved in that shot gets so caught up in the moment, and there’s pressure on everyone. People perform well with pressure. It’s interesting: when you look at a movie like Birdman, I think, “Boy, every day on that set must have been so charged in the way that one day for us was charged,” and you realize how it brings out so much greatness in all the performers, whether it’s the focus puller or the effects guy or a particular stunt guy or the [camera] operator. All these people have to be really on their game in those moments. On top of all that, the director has to be on his or her game as well, because you have to make sure that the pacing and the performance of everyone involved is such that this is actually gonna work. But after doing that, it actually got me excited to do more of that, and that’s why in Day of Reckoning we designed more sequences to work that way.

That’s that kind of “video game aesthetic” that I like. People talk about the video game aesthetic, and to me, what really defines the video game aesthetic is there are no cuts. It’s usually like a third-person shooter game. It has that [feeling of] moving through a space, like

Grand Theft Auto or

Call of Duty, in real time. What you’re doing is you’re giving the viewer a subjective perspective on the action, which to me is always more interesting than a God’s eye view. It’s often more interesting not to see what’s around the corner – to come upon that corner with a character and

then see what’s around the corner. There are plenty of different approaches that work, but when I’m approaching an action sequence, or even a movie in general, or when I’m writing, I’m thinking, “What is the point of view right now? And what points of view aren’t necessary? What points of view are getting in the way of creating tension?” For example:

Saving Private Ryan – the Normandy Beach sequence – except for one shot that I remember of the Germans’ gun turret, that whole thing is basically spent with the soldiers as they exit the boats, go through the water, hide, and work their way up through the hill. The perspective is with them and you’re not seeing the other side, and that’s what it makes it so visceral. Whether you’re doing a “one-er,” or you’re cutting to camera, what I like most about it is the subjectivity.

Q: You touched on this briefly before, but tell me how you hooked up with the film’s composer, Michael Krassner, and did you know from the start that you wanted to pursue this kind of John Carpenter synthesizer style?

Hyams: One of my favorite collaborations on my films as well as my documentaries has been working with Michael Krassner. What I love about him is he’s not a traditional film composer. He doesn’t come at it with a film composer’s perspective. He’s a musician; he writes and performs songs. If you ever hear him play out, he’s actually a Bob Dylan-style finger-guitar player. But really he’s an experimental musician. He’s very, very educated about all kinds of experimental music. The movie scores that I like the best and respond to the most are not traditional scores. You know, I love guys like Cliff Martinez, whose scores are not necessarily directly to picture – they’re more about setting a vibe and a mood and a feeling, and creating things like Kubrick’s scores in

The Shining and

A Clockwork Orange. Those are things that I really respond to. And so does Michael. So the way we go about creating these soundtracks is very different than traditionally editing a movie, handing it over to the composer, he writes music, and there you go. On anything I’ve ever done with Mike, the first thing he likes to do is assemble the musicians, and it’s always a different group of musicians. It’s people who are good at different things, and every movie has call for something different. In the case of this, I probably threw out Carpenter and Tangerine Dream to him, because my knowledge is a little more film and soundtrack-based, where he is much more aware of general musicians and people I had not been aware of that he’s turned me onto. I think I came to him with those ideas and the idea of a synth-based score, along the lines of Carpenter/

Sorcerer-era Tangerine Dream. I think the main piece of music that I played for him was

“Betrayal” from Sorcerer, which has always been one of my favorite pieces of music. From that, Mike went and put together an eclectic and interesting team of musicians and began recording music – not to picture, just recording music – and then sent me pieces. I would start editing and work with his music and start putting that music to picture, and I would send him scenes and he’d do some more recording sessions. Generally, the recording sessions are not to picture at all – they are big improvisations. That’s how we did the documentaries. There would be these improvisations that I would go and find parts of, and we would do overdubs of that. For

Regeneration, we kind of changed that method.

At a certain point, once we collected enough pieces and put them together, then we started doing some straight-up scoring to the picture, which was really fun, and again, we did it in a very non-traditional way. It wasn’t at a proper recording studio where you have the picture up on a big screen. We were kind of doing it beat by beat to keep it as loose as we could, and then we would do overdubs and overdubs, so it became a very organic process, as it always is with him. My attitude was to come up with a very general thing with him to see what he came up with, because it’s always ten times more interesting than anything you or any composer would come up with, because he’s never coming at it from the obvious perspective. We usually take all of the music he creates and then find a way to make it work in the sense of hitting certain movie beats and thriller beats. I don’t like to put the shackles on him. I want him to experiment when creating it. For something like Day of Reckoning, which was still Mike Krassner but with some different people, those were almost all improvisations. Everything in that movie is born out of long improvisations.

Q: I know we’re going on many years since Regeneration was released, but no official soundtrack was ever made available. Has Michael given any thought about doing a self-release of his Regeneration score through Bandcamp or iTunes? Or does Sony own all the rights to the music? This kind of Carpenter-like music is making a huge comeback in genre films.

Hyams: There are some cases where music we did create has been released in different forms, and made it onto different compilations, but never as a straight-up album. It’s a good question, it would be great. I wish that we could release it as a soundtrack. I don’t know, I’d have to ask him. I know there’s always been thought about whether or not Sony would let us do that. I guess that would be a question for them when the time comes. But I think that would be great. The stuff he’s done for all the movies I’ve done is so cinematic, it would be a great tool for filmmakers to listen to, or just enjoy – not even as a tool, but something to listen to and get inspirations from.

Q: I don’t know if you’ve gotten the chance to pick up a copy for yourself, but Carpenter released “Lost Themes” not too long ago and it’s excellent.

Hyams: Oh, you mean that collection he just put out?

Q: Yeah.

Hyams: I did, it’s fantastic. He did it with his son, right?

Q: Yeah, he did it with his son, Cody. It’s interesting to listen to, because even though it was produced within the last few years, you can almost picture the era of his career when certain tracks could have been made. Some tracks sound like Prince of Darkness and others like something circa Halloween 3.

Hyams: Totally, you’re right.

Q: That kind of sound, like I said, is coming back, bigger and bigger. Now, especially for these low budget productions, in keeping with the spirit in which they were originally made, it’s become having a synthesizer and one guy who gets it, instead of the strings and the horns and the whole orchestra.

Hyams: Yeah, and again, guys like Cliff Martinez, and the scores he did for Nicolas Winding Refn and Soderbergh are my favorite scores ever.

Q: The very ending of Regeneration suggests that we could be seeing the Captain Burke character, played by [UFC fighter] Mike Pyle, return as a universal soldier. Was that meant to be a potential plot point for a future installment, or was that more of an indication of how detached the US government was in taking these soldiers who gave their lives for their country and then just replicating them like they were nothing more than engines on an assembly line?

Hyams: That ending was actually in the original script and it was one thing I really loved. I’m sure the initial idea of it was something that could have either been something literal that could have been carried on in the next one, but in the way I ended up deciding to go with

Day of Reckoning, it was less about picking up immediately where we left off and more imagining something…it was almost like my concept of

Day of Reckoning suggested there was another movie that we skipped in between and that we’re imagining everything has advanced. Truth be told, the first script I wrote for

Day of Reckoning was actually set in the future. It was supposed to take place decades later, and that script was actually rejected, so I had to write a new one. But the concept was…I love the idea that the Universal Soldier program was going to move from this kind of zombie/frozen/regenerated dead soldiers into genetic engineering. It would basically be growing these guys from scratch and cloning them. And I loved taking it in that direction, and by doing so, that’s why I think

Day of Reckoning suggested that there is no more mythology of the unfrozen dead soldiers. That’s sort of over. It’s almost like the Luc Deveraux character is the only holdout from those original guys and that everything else was about creating them from scratch, kind of creating monsters that are literally born into what they’d become. They have no past. The original

Universal Soldier was about taking people who had pasts and turning them into these zombie drones, but their past and their memories start kind of creeping in and affecting them. The point of

Day of Reckoning is that if you create monsters who are potentially full-grown killing machines, that seems very convenient, but the fatal flaw is that they have no memories, and we played that out – that existential crisis with Dolph’s character in

Regeneration, right? What happens when you have no memories? And you’re in a perpetual state of déjà vu? So that was when we decided to then take it into the realm of creating memories in order to motivate these individuals. You know, I just loved that whole Philip K. Dick thing. That was what got me. That was the idea that got me interested in making

Day of Reckoning and creating a story where you have characters that are not even aware they’re being directed by an outside force. Questioning the free will of the individual seemed like a really fun concept to explore.

Q: How soon did work get going on Day of Reckoning following the release of Regeneration on video? Was the studio immediately into the idea, or did it take time for the reaction of Regeneration to materialize?

Hyams: It took a little time. Regeneration came out in 2009 and I was not approached to come up with a concept for another one until mid-to-late 2010. And like I said, in 2010, I was asked to submit a concept, so I wrote up a treatment, which was approved by everybody involved. I then wrote the script, and that script ended up getting…they ended up balking at the idea. Not everyone was on board, and they felt like I had just taken it too far away from the original story. I think people were afraid that it just bore no resemblance to Universal Soldier, so I went back to the drawing board and there were lots of discussions and negotiations of ideas. Eventually sitting down with the producer [Moshe Diamant], we came up with the storyline that exists now. And we sort of came up with that idea in some ways together as far as the kernel of the idea – that the movie would begin with an event that never actually happened.

Day of Reckoning’s production company was set up down in Baton Rouge, so to be able to write this new script and be down there with them and be on the payroll, that’s why I directed Dragon Eyes. That was basically…by directing Dragon Eyes, I could stay down there in Baton Rouge and work on this script and get it approved by everyone down there. That’s kind of how that all came about.

Q: Your father was the director of photography on Regeneration but not Day of Reckoning, so I have to ask you: what was it like to fire your father in between films?

Hyams: [laughs] Yeah, it wasn’t exactly firing. That’s pretty funny. I think it was pretty well understood that, like I said, in order for Regeneration to get made, his involvement was necessary, and then at a certain point, I think it was clear that, from my own career standpoint – as much as I would love to keep doing movies with him – it wasn’t a good look for me to have. I kind of needed to prove that I didn’t need him. From a personal PR standpoint, it was nothing beyond that. As far as our working relationship, it was a normal director/DP relationship. But at a certain point, it was important for me to prove to whomever needs to be proven to that I can do it myself. That was completely understood. Especially because Day of Reckoning – this is a completely separate issue, and my dad could have definitely handled it – was shot in 3D. That was not something I wanted; it was something I was adamantly against, because I knew it was not going to make our lives any easier.

Q: Well, to me it didn’t really lend itself. I mean, on paper, you’re making Universal Soldier 3 or 6, or whatever it technically was, so you can easily attach that to the title and think, “Oh, well it’s the new Van Damme movie – let’s put it in 3D,” but when you see the finished product, it kind of cheapens it in a way because this film is so much more than just some action movie you could apply 3D to.

Hyams: True, and that is how they sold it. It had nothing to do with the concept. It was just…Van Damme/Universal Soldier and there you go. In a strange way, even though the 3D was totally irrelevant to me, it did inform the way we shot it a little bit, because we didn’t use long lenses; we didn’t use a lens any longer than a 40mm; it was a little more longer takes and wider shots – stuff that I like – but if you do long lens and lots of quick cutting, that doesn’t really lend itself to 3D. So, in a weird way, because we were forced to do 3D, we said, “All right, look – we need this to work primarily as a 2D movie, but it should be cool in 3D, too, if anyone ever sees it in 3D.” We had to be very efficient in our number of set-ups and all of those things. In a strange way, the movie was completely reverse-engineered, because once I knew it had to be done in 3D and I knew what our schedule was, and our budget and how tough that was going to be to pull off, then it was very clear to me that we needed performers who could do their own stunts and be able to do that. We needed a protagonist who could do his own stunts and do a lot of choreography in unbroken takes, and that’s what led me to Scott Adkins and creating a character like that. To me, it wasn’t a case of we would have the time, or aesthetically have the desire to be doubling people, and so we had to concede to it in a certain way. I wanted someone like Scott who could really do that kind of stuff. Not to say that Van Damme can’t – in the opening of JCVD he does a long, unbroken take and he did one for us, too – but I knew what his time commitment was going to be down there shooting for only a handful of days and how much prep he was going to have, and I knew that I wanted to create a character who didn’t necessarily, for the audience, know what that character was capable of until midway through the movie. That was going to be the fun of that. That kind of self-discovery for the protagonist. He doesn’t really get busy until halfway through.

Q: He has that awesome sporting good store scene when he catches the bat one-handed, and he looks at it, and he kinda realizes there’s this thing inside him that he doesn’t quite understand, but he’s just turned it on.

Hyams: Yeah, it’s kind of like the Neo/“I know kung fu” moment. To me, the whole movie was designed to build to that point, and I think for Larnell Stovall, the fight choreographer, who is the best in the world at that, it was a great challenge for him to create action leading up to the action where we could never really see what this guy was capable of. We had to have him be victimized early on and then create a fight that has a certain moment where he figures it out. That was one of the great collaborations was working with Larnell and what he brought to the table and how he used his action choreography to help propel the narrative. That was really one of the most exciting collaborations of that movie for me. It was certainly a guy I’d love to work with again.

Q: The fight choreography in that scene is incredible. And that scene – I picked-up the Blu-ray version that was released in Canada, because after doing some research, I’d discovered that for whatever reason, Canada got the unrated version to release, whereas it was the R-rated cut in the States. And for that finishing move with the baseball bat scene, I had to have it uncut.

Q: I didn’t realize at first, because the first time I saw it, it was the rated version, and it was already so violent I didn’t think anything of it. So when I started doing the research and I found out there was an unrated version in Canada, I thought, “Wait, there’s another cut that’s even more violent?” So I went right to Amazon.ca and ordered it.

Hyams: I really appreciate that. That was my greatest frustration with that movie. Not that we had to make an R-rating, but I was always kind of promised all along that we were going to be able to release the unrated version – that was supposed to be the main DVD release – but for some reason that’s not how it went down and that was really disappointing to me. I guess most people who saw the version as it was didn’t seem to notice so much the editing that had been done, and to me I could take or leave. You know, out of the violent things I had to cut, that was the one that bummed me out. That was the moment that I wanted to have, which is funny now; to be doing a TV show for Sy-Fy where there’s absolutely nothing in that movie that you couldn’t do on Z-Nation. If that’s for better or worse, I don’t know, but it was amazing having to deal with the ratings board. It’s not like if you are Quentin Tarantino and dealing with the ratings board where you kind of get to submit a cut and then you go back and submit another cut and keep doing that. I had ONE shot. I submitted it, they gave me an NC-17, and they said, “You have one more shot and that’s that. If you don’t get an R-rating, you don’t get a theatrical release from Magnolia. They won’t pick it up.” So that was a pretty tough situation, unfortunately. In some ways I feel I had to go overboard in some stuff rather than refine it.

Q: You hear about filmmakers who purposely overshoot – horror directors especially, because they know they’re going to get savaged by the ratings board – so they think, “Let’s just shoot a bunch of easy-target excess crap and we can cut it out to appease them,” but sometimes that content actually slips through and the ratings board pass it as-is.

Hyams: Yeah, I did that. I tried to. I even put some extra sexual content in the brothel sequence that I wrote off as being the thing that I would have to cut out, so I threw some things in there, but, you know, it’s so subjective – ratings. It’s fine. I could probably find things in all kinds of movies that have passed that are way more extreme, but what I came to realize, which is sort of the the incredible irony of it all, is that if you portray violence as being dark and bad and consequential, they’ll flag you for it, but if I show you the same violent thing and had fun music behind it, they’ll pass it. Which is like kind of the opposite message: shouldn’t violence be bad? Shouldn’t we cringe at violence? But not according to the ratings board.

Q: The ratings board is an outdated institution. They’re the equivalent of the person who swabs rubbing alcohol on the arm of the prisoner who’s about to get lethal injection.

Hyams: [laughs]

Q: They’re irrelevant; I’m not even sure they serve a purpose anymore.

Hyams: I’m not too sure of it, either. But it is kind of funny, because I’ve always tried to make violence look dark, you know? I try not to celebrate it. It doesn’t mean I don’t…I love violent movies, I have no problem with them. I love Tarantino movies. And I don’t think people have to apologize for any of it, but for me personally, I always like the violence to have consequences on the characters, on the perpetrators, on the victims. Because that’s the way I look at it. So when I’m on a big fight scene, it’s always a challenge dealing with producers or execs or whoever it is because…when you play a fight and just hear the sounds and don’t hear the music – don’t hear fun, high-tempoed music – people sometimes think it’s too raw and it’s a little too violent that way. To me, I like that. In

Day of Reckoning, the idea was action as horror. That was kind of our concept. And it’s because we couldn’t afford spectacle. We couldn’t afford to do

Fast and Furious – you know, cars flying through the air. We had no effects budget. So the only thing we could do to create tension was to make you scared of a punch and scared of a hit with a baseball bat and frightened when a gun goes off. That was just how we approached it in the name of entertainment. It’s interesting how people can still be averse; they’ll look at that and read that as more violent, but when in fact it only sounds more violent than it is. It isn’t necessarily more violent than it is.

Q: Regeneration made it a point to drop most of the cheeky humor of the original film, but alternately, Day of Reckoning sort of re-embraces the humor again, only it’s of a much more dark, gallows-humor variety. I’ll point out the brothel shooting sequence where the old madam gets shot in the head and she’s got that look of bewilderment, and she remains still for a bit before her head sort of splats down onto the counter.

Hyams: [laughs] That was our Coen brothers moment.

Q: What was it about this particular iteration that you felt humor would be more appropriate?

Hyams: I think I was looking at it because the humor was coming from a place of…when I was making that movie, I was thinking a lot about David Lynch, really. David Lynch’s movies – the ones that I love – have this amazing ability to kind of create this foreboding sense of dread, and you don’t exactly know why you’re feeling it from a plot perspective, but you’re feeling it because of the sound design and the juxtaposition of a particular sound with a particular image that in one way could be mundane, but in another way somehow has dark connotations. And in a movie where you’re supposed to be questioning reality because you’re seeing it from the perspective from this character, I thought it could allow for that. Part of the movie is this fun-house mirror version of reality, so there is a place for moments of humor. Even Regeneration has its moments. I think the Andrew Scott shaggy dog story and his final line – to me that’s pretty funny. His death and all that.

Q: I absolutely love that look on Dolph’s face in Regeneration where he’s almost about to have an emotional epiphany, like a revelation, and then this utter shocking moment – it’s one of the best villain dispatches I’ve seen, ever. The first time I watched that scene, I flew back and said, “Oh shit! That was awesome!”

Hyams: Good! Yeah, that was always the intent. In the end, again, that’s a very Carpenter kind of thing to balance. In Carpenter, the humor is never that far away.

The Thing is as dark and serious as you get, but there was always room for humor relief. So I think in

Day of Reckoning, that sporting good store, that last moment…the only real reaction to that is to laugh. That would certainly be

my reaction. And the madam at the brothel, and there’s even that moment in the scene where Scott fights Dolph and he sticks the knife in Dolph’s hand and Dolph just starts laughing. That was really funny to me. We came up with that one on the day. But again, people bring humor to the situation and I think that’s great. These movies want that, but to me the way to achieve that is to counteract it with some of the most serious shit you’ve seen in your life and follow it with something funny. It doesn’t get any more serious than that opening scene, but there was a concept behind that – there was the idea that we were trying to, in many ways, play off of revenge movies. You know, revenge movies always start with a crime against the protagonist, usually their families. Make it

Death Wish, whatever you want. But it’s basically a crime that is telling the viewer: “Now this guy has to rip everyone a new one throughout the rest of this movie”

[laughs], so its like, “How far are you going to go at the beginning?” And that becomes, “If you’re going to implant memories in a guy to make him a homicidal maniac, what would he do?” So that’s what we did. And not that that’s humorous, but there is some kind of gallows humor associated with all of it. Horror and comedy are close cousins.

Regeneration played it a little more serious, but it also had a lot more general exposition. There were a lot of scientists and doctors and commanders spouting off exposition.

Day of Reckoning was much more of moving through an amnesia victim who is our kind of Phillip Marlowe taking us through this story. He was our Jeff Lebowski, if you will. He’s going to take us through this story, come upon a bunch of different characters, and in the process, he’s going to discover who he is. When he finds out who he is, that’s how he can absolve, because

he is the monster.

Q: There’s a really great moment in Day of Reckoning in the final act when John is in the process of having his memories removed via surgical drill by the Dr. Su character (David Jensen). The film presents this doctor character as this sort of rogue doctor who is working to free all of these soldiers from their own artificial minds. But you choose to shoot, from John’s point of view, this upside-down shot of the doctor as he’s drilling, and his grimace now suddenly looks like a maniacal smile. I’ve always wondered about this scene – if there was an intention behind manipulating the audience’s view of this doctor, who had appeared sympathetic and “good,” but who now, from John’s point of view, looks devious, as if to suggest the only thing John can now trust is his own fabricated sense of self that’s come to define him. I would love to hear you talk about that decision to shoot that the way you did.

Hyams: The point of the story is ultimately what “truth” is, in many ways. John is going in search of truth, but what he comes to find is he chooses his delusions over the truth. Because his fabricated self, his fabricated wife, his fabricated child – those were real, because those were the only things that connected him to being human. He experienced love. The idea is that this scene begins with this seemingly benevolent doctor who’s going to help John, and once it gets going, as the scene progresses, from John’s perspective, this guy goes from being someone who is trying to help him to someone who is trying to take his humanity away, because he’s taking memories away. When we look at him now, from that perspective of the guy who is going to erase the memory of his wife and child, he somehow becomes an antagonist in the middle of the scene. We always wanted to shoot everything in the movie from John’s perspective, [including] that shift that happens in the middle of the scene. In this movie, people may seem like an antagonist – Deveraux, for example, you believe is the antagonist from minute one, but it turns out he’s not the antagonist. The antagonist is really embodied by the character of Agent Gorman [Rus Blackwell]. That’s John’s true antagonist – someone who comes to him as a friend early on. That was the most fun part of the movie to me: playing with those narrative ideas – that when you tell a story subjectively, your ideas of who is a protagonist, who is an antagonist, can become flipped.

One of the things I wanted to explore in our film is: we are nothing more than our memories, and our reality is far less important than clinging to those things that make us human, especially for these beings who have incomplete lives and incomplete histories – that we are pretty much the product of our past. So what would happen if you created a person that didn’t have a past? And what would happen if you tried to create that past? And going a step further, the idea was taking the revenge story idea to its most ludicrous. To take a step back and say we were going to try and play a trick on the audience to make you think Deveraux is the antagonist, but really he’s the protagonist. This is how I came upon that; this is how that idea was born: Luc Deveraux is at war with the government for creating him, right? He’s at war with his creators. In doing so, he’s creating his own army and eventually breeding his own army of super-soldiers like him and they will essentially stop at nothing until they have destroyed the government, and in essence taken over its humanity. So the government tries to create a super-soldier who’s motivated by revenge, and the revenge is for the killing of his wife and daughter. When Deveraux and John are having that fight at the end, what Deveraux realizes is that this is a guy who is just as, if not more, powerful than him, and he can either kill this guy, or unleash this guy on his creators. What Deveraux figures out is that by sacrificing himself, it will put John on a continued quest for the culprits. When the movie ends, what John realizes is that yes, Deveraux killed his family, but he tells Agent Gorman, “You put him up to it.” What you should extrapolate from that is that Agent Gorman is just a middle-manager, so who put him up to it? That’s the next guy on the list. And then who put him up to it? So basically, this guy is not going to stop until he wipes out humanity. It’s our Dr. Strangelove ending, really. The government created its own doomsday device.

Q: I love that the movie ends with a close-up of the bracelet on John’s wrist. In his mind, his very real daughter had given that to him on his birthday. And even though she never existed, he’s going to keep that. That’s going to be his. It’s one of those sad, tragic endings that you can’t help but love – along the lines of Memento – in that this guy is going to completely embrace an artificial past because it’s comforting to him to believe that it was real.

Hyams: And in doing so, he’s going to kill EVERYBODY.

Q: [laughs] Which is awesome, by the way.

Hyams: It’s a warning to science: be careful what you create.

Q: What were the reactions of Van Damme and Lundgren to their roles being reduced to supporting characters in Reckoning?

Hyams: They were ultimately okay with it because let’s face it: a lot of it starts with money and time negotiation. In the end, they were making good money for a very short shooting schedule. They were still very important to the movie. They were not side characters, they were pivotal – guys who were centers of the story and the plot – and it just made sense to me that, if the end of

Regeneration was Luc Deveraux running off into the distance, then the next movie should be about finding Luc Deveraux. You could’ve had a movie in between where you’re with him on the lam, but to me it’s more interesting to see what he’s become – to look at it several years down the line. They liked the movie – I know Dolph liked the movie, and I think Jean-Claude did as well. Again, once they approved the idea and where we were going and felt good about the script, then I felt that my goal was not to embarrass them, and promised them I wouldn’t. That’s all actors really want to know for sure: that you’re not going to make them look foolish, because they’re at your mercy once you go and put the movie together. You’re the director and they have to trust you. So they were taking a big swing with it, and it took some people involved with the movie some getting used to. There were certainly some executives who didn’t know what to make of it at first. It wasn’t until we were getting some critical praise that they were comfortable with it. I think some people were looking at me, like, “You had an easy let-up, and you turned it into a 360.” I took something that had a low degree of difficulty – hand in

Universal Soldier 4 – and turned it into something complicated

[laughs], but to me, why

not do that?

Q: Do you think it’s possible, if you were in the position to make another Universal Soldier sequel that followed in the footsteps of your entries, that Van Damme and Lundgren might not appear at all? Or do you feel that they should always be involved, even if it’s in a minor capacity?

Hyams: That’s a really good question, and I’ve certainly thought about it. I’ve considered the idea and thought about concepts. Maybe at some point the story moves on and what more can you do with those characters? And then another side of me thinks that it would be important to the audience to have those characters represented. I can’t say I know the answer to that, but I know I’ve certainly considered it. Because you start to run out of what you can say. Like Day of Reckoning, I had to think really hard about what to say with those characters. Maybe the answer is: those characters have to exist almost in a different capacity.

Q: From an audience point of view and probably from an executive’s point of view, the presence of Van Damme and Lundgren would be pretty important. I know from my personal point of view – and this will sound funny, but from a romantic point of view – even if it would make more sense not to include their characters somewhere down the line, a part of me is going to want them involved because they are so involved in the mythos. In the same way that all this news is circulating about Neill Blomkamp possibly doing Alien 5, with Sigourney Weaver coming back and Michael Biehn possibly coming back. The initial part of you – the geeky part of you – says, “Yes, I want this!” But then the rational part of you kicks in and you think, “How can you ever pull this off?” If he’s going to respect the mythos established by Alien: Resurrection, is Ripley’s character going to be the weird clone version? I’m not really interested in that. And how are you going to bring back her back, and Michael Biehn, and account for their ages? There are all these questions that would be easier to avoid. But then that other part of you starts yelling louder and just wants to geek out at the idea of Ripley and Hicks coming back. So it’s a really tough balancing act.

Hyams: I think you’re right about that. In the end, you probably need them in some way. As far as Alien 5 goes, I do think you need Ripley. It’s not Alien without Ripley. And I do think Hicks would be cool. From my understanding, they’re kind of picking this up from Aliens. I don’t know how they’re going to account for the age, if they are going to account for the age. Maybe this will somehow be an alternate conclusion episode of the franchise, pre-clone Ripley.

Again, my interest in that is because Neill Blomkamp is doing it. I’m interested in his Alien. If someone else were doing it? I don’t know that I’m interested. But if he’s doing it – whatever the hell he does with it – I’m interested. Otherwise, I don’t think the world really needs another Alien film.

Q: Well, that’s the thing about sequels. You won’t know if you needed one until it’s already arrived. I mean, did the world need James Cameron to come in and do Aliens? Not really, because the first film is classic, has a finite ending, and it stands on its own. But Aliens is awesome, so it’s earned the right not only to exist, but to be as celebrated as it is.

Hyams: Well, in a way, the world did need another one, because Cameron turned it into an action movie. Instead of one alien, it was a bunch, so to me there was a purpose for that. As far as sequels go, if you’re saying something new with it, then there’s a reason for another chapter to exist.

You know, movies are becoming TV now. We want characters we can follow into multiple episodes and multiple chapters, and if that’s what the public wants, then that’s what we’ll see.

There was a time when “sequel” meant it was going to be terrible, and now that doesn’t mean that anymore. Post-Nolan’s The Dark Knight trilogy, sequels get a bigger budget and sometimes make a better movie. We could certainly use more original ideas and less superhero movies, but if this is the arena where our great directors are going to be working, then let’s see what the great ones do. I’m excited for Blomkamp’s Alien, but I hope he keeps making original films, too.

Q: Have you ever had contact with Roland Emmerich and Dean Devlin (who directed and wrote, respectively, the original Universal Soldier) regarding your entries in the series?

Hyams: No. I never did. I’ve never met them. I would love to meet them, but no. I don’t even know if they’re aware that those movies exist. I’ve never spoken to them.

Q: I would love to be a fly on the wall of Roland Emmerich’s living room the first time he watches Day of Reckoning. Because I—

Hyams: [laughs] He’d be saying, “What the fuck is this?”