Every once in a while, a genuinely great horror movie—one that would rightfully be considered a classic, had it gotten more exposure and love at the box office—makes an appearance. It comes, no one notices, and it goes. But movies like this are important. They need to be treasured and remembered. If intelligent, original horror is supported, then that's what we'll begin to receive, in droves. We need to make these movies a part of the legendary genre we hold so dear. Because these are the unsung horrors. These are the movies that should have been successful, but were instead ignored. They should be rightfully praised for the freshness and intelligence and craft that they have contributed to our genre.

So, better late than never, we’re going to celebrate them now… one at a time.

Dir. Mark Pavia

Dir. Mark Pavia

1997

New Line Cinema

United States

Stephen King is perhaps the most prolific author who has ever lived. Interesting that his home base is the horror genre—something often derided for its offensive, controversial, or corny subject matter. There’s no arguing the man has given one generation after another unending nightmares about clowns hiding in sewers, corpses in hotel room bathtubs, and recently resurrected childhood pets. He’s written tales of utter fear married with genuine quality, and he, like many of his colleagues, hands his work to filmmakers on a silver platter, hoping they will achieve a same result. Unfortunately, that is hardly the case. In general, nine times out of ten the book will always be better than the movie it inspired, but with King, it sometimes seems as if there is some cosmic force out there willing to do anything to prove it, for the chances of a successful King novel to screen transition is generally 50/50. Famous filmmakers with various levels of prestige have tackled King over the years: Stanley Kubrick, John Carpenter, Rob Reiner…the list is truly endless—yet despite the director’s pedigree, it didn’t always work out. Lawrence Kasdan, for instance – the man who brought you The Big Chill and Wyatt Earp – couldn’t quite turn Dreamcatcher into anything more but a bloated Hollywood A-list joke (although the source material did not reflect the best of King’s work). Tom Holland, who had previously contributed the horror classics Child’s Play and Fright Night (as well as the script for the quite-good Psycho 2), couldn’t pull off Thinner. Even George Romero, who hit one homerun with Creepshow, couldn’t quite make The Dark Half work. Lastly, let’s not forget poor Mick Garris, who just keeps trying.

And that’s just when it comes to novels.

When it comes to King’s short stories and novellas…oh boy. For every decent story-to-film transition (1408, Apt Pupil), there are dozens of inexorably poor attempts (Lawnmower Man, The Mangler, eight – count ‘em – eight Children of the Corn movies) whose odor of excrement still waft across the land. Many filmmakers have tried; most have failed. It would seem that only Frank Darabont possesses that rare ability to repeatedly turn King’s shorter works into amazing films. Most folks point to The Shawshank Redemption as that shining example, but The Mist is an underrated and nasty little tale of monster mayhem and the ugliness of humanity (even if the ending is a bit too mean-spirited for my taste).

With that said, when I tell you that a filmmaker with very little previous credits to his name adapted one particular King tale about a vampire pilot, and it stars the angry guy from Project: ALF, I’d expect you to be suspicious, if not downright cynical.

How horribly wrong you would be. In fact, next to Shawshank and Stand By Me, The Night Flier is perhaps one of the best adaptations of a King short to date.

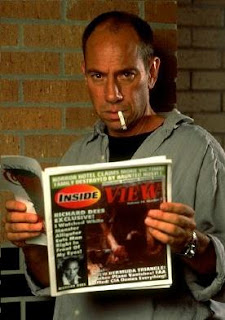

Miguel Ferrer is Richard Dees, an unscrupulous reporter for a tabloid called Inside View. He has no qualms with hiding in morgues all night, or doing…certain things…with morgue attendants to ensure he obtains the perfect photographs to accompany his stories. And he isn't on-screen for more than ten seconds before he snatches a galley proof out of someone's hand and demands to know where his "god damned dead baby" picture is. It's quite an introduction to a character, and right away lets you know just what kind of "protagonist" with whom you'll be spending your time.

Dees has made a decent living writing slime (which includes loving homage to other King works, such as Thinner and Needful Things), so it’s much to his chagrin that his equally slimy editor, Merton Morrison (Dan Monahan of the Porky’s films), forces upon him a newbie reporter named Katherine (Julie Entwisle) to be his partner. Dees is not terribly excited at this prospect and does nothing to camouflage his disdain for her.

In a smoky bar one evening, Dees tells Katherine how the job and the sick things she’ll eventually see will crawl inside her like a cancer and fester until she either kills herself or goes mad—citing his former co-worker named Dottie (whom Katherine is replacing) as the example. Dees lives by the coda “Never believe what you publish, and never publish what you believe.” He also lives an isolated life – one primarily spent on the open road – and he genuinely seems to prefer it that way. There’s not a single scene that takes place in Dee’s home—bars, yes; the office, yes; dingy motel rooms, the open road, his own private airplane; all yes. But the man, sadly, has no real home of his own, and that speaks volumes about the kind of person he is. Though he preaches never to believe what he publishes, the job clearly encompasses his whole life. He’s not the most balanced person you’ll meet, and his temper flares with little prodding.

At the editor’s insistence, Dees begins following the trail of Dwight Renfield, a so-called vampire pilot who lands his black Cessna airplane in isolated airstrips and helps himself to the hapless victims unfortunate enough to dwell close by. Before feasting, however, Renfield bestows upon them some kind of trancelike state, leaving his victims lucid and almost high. The victims tend to be elderly (meaning, unable to put up any kind of fight), but those friends and witnesses claim that in the days leading to their death, they never looked better—bright skin and eyes brimming with life; an interesting effect of being preyed upon by a vampiric creature.

There are some creepy and ghastly sights along the way: Someone’s head ripped off their neck and staring, upside down, with their dead eyes; a woman, whose blood was cleanly drained from her body, lying peacefully on her bed; even an utterly demonic looking dog that leaps from the top of a trailer and chases Dees to his car…but then suddenly reappears on top of the trailer again, sitting calmly and stoically, before vanishing altogether. (Scenes like this make me wish the currently out-of-print DVD contained a director’s commentary, because I’d love to know how they made the dog that insane looking.)

During the investigation, Dees cock-teases Morrison by telling him he’s covered excellent ground, but refuses to spill because he can feel the story is about to get bigger and weirder. Morrison, refusing to wait for Dees’ version of the story, instead sics newbie Katherine on the trail, as well—not just in an effort to get the story on the shelves as soon as possible, but also because he gets his rocks off on playing his seasoned reporter and his brand new hire against each other. (In fact, his last scene in the film ends with him maniacally laughing in the dark solitude of his office, knowing the two at-odds reporters are both heading toward an inevitable and ugly confrontation.)

As Dees falls deeper down Renfield’s rabbit hole, he clings desperately to his credo of publishing and believing he has so often followed. Things become increasingly real for Dees, however, until he can no longer help but become entangled in the morbid investigation. The idea of regaining his top dog position at Inside View (which pathetically, at the end of the day, is really not an enviable position at all) becomes too enticing for Dees to pass up. That’s a decision he will ultimately come to regret.

Begin Spoilers.

On the surface, The Night Flier is just your fun and bloody vampire tale, but underneath, there's quite a bit thematically going on. Great pains (though subtle) are made to show that Dees and Renfield are kindred spirits. The first and most obvious would be the fact that they both own planes…a similarity purposely made obvious to lead you to see the less obvious similarities on your own. To start, they both live an isolated life, existing not in a home, but in the skies above. Perhaps most ironically, they are both bloodsuckers, preying on their unsuspecting victims in different ways. Dees has spent his entire life chasing death, while Renfield has spent most of his afterlife spreading it; the actions of both have brought nothing but pain and misery to all of their victims.

The Night Flier is about transition. When Dees speaks of his former co-worker, Dottie, in the beginning of the film, there's a brief flashback of him standing at her bathroom doorway, staring at her lifeless body in the tub. Before you can even begin to wonder why he is there, he raises his camera and takes a picture. At that point, she becomes to him nothing more than headline fodder. At the film's end, Katherine, too, assumes the "role" of Dees and publishes a story outing him as "The Night Flier," also effectively killing the trail of the true killer. There's a strange kind of hope for her character—the film ends with a close-up of her face, hardened by all that she has experienced, but she truly has learned from Dees his one commandment: Never believe what you publish, and never publish what you believe. Having seen Renfield take off into the stormy night, she decides then and there not to pursue. She has seen what chasing the truth has done to a person, and so she shifts the blame to Dees...who all along was just another side of Renfield, anyway. While the true Night Flier is not the one whose face becomes splashed on the front page of Inside View, Dees deserves to be just as vilified.

Speaking of transition, how much credence should I lend to the fact that the film's finale takes place in a car rental agency called Triangle Budget Rental? After all, Katherine becomes Dees; Dees becomes "The Night Flier;" and "The Night Flier" becomes a story that will never be published because Katherine sees the truth of it, and hence believes...which is the only ideal Dees ever really lived by.

End Spoilers.

Dees is truly despicable in almost every sense – he has not one positive trait – yet he becomes a character you root for, even sympathize with, as the story progresses towards its shocking conclusion. It’s the strength of Miguel Ferrer’s performance that enables this conflicted support, as he brings a lot of weight to his role. Ferrer has spent the majority of the last decade working in television, his last meaty film role being in Jonathan Demme’s 2004 remake of The Manchurian Candidate. He is one of those many character actors that do not receive nearly as much attention as they deserve.

Really, for a low budget affair, the entire supporting cast does a great job. Monahan as Morrison oozes with that special kind of slime you can't help but secretly adore, and Phoebe Cates-lookalike Entwisle as Katherine contributes a believable performance in her first (and only?) film role. Special mention must be made of John Bennes as airplane maintenance man Ezra Hannon. His very brief moment of screen time comes across as probably the most genuine performance in the film. With his engine grease-covered hands and face, and his filthy jumpsuit, he looks every bit the part. Before checking out his career on the ol’ IMDB, I was convinced he was a real New England native who managed to find his way into the movie. It’s little things like this that give The Night Flier its power. Actual effort went into the movie, and it shows. Low budgets can be a hindrance, but talent and passion can and will always make up for it—so long as you’ve got the right people in front of and behind the camera.

The red stuff flies fast and furiously—the legendary KNB FX boys do not hold back. And the last ten minutes contains some of the scariest, most fucked up (without going overboard), and expert execution I’ve ever seen in the horror genre. I love watching this film with people who have never seen it, because this ending sequence always leaves them shifting uncomfortably on the couch.

Composer Brian Keane turns in a nice little score, filling it with sad melancholy and subtle horror. He has spent the majority of his career scoring documentaries for television, and his style of small, under-the-surface music serves the film quite well.

As an aside, The Night Flier is a movie that plays quite beautifully in black and white. The natural noir aspects of the film play well against the stripping of color, and it makes you look at the film in a new way. I definitely recommend turning off the color the next time you watch.

Writer/director Mark Pavia enhanced the original story quite a bit to turn it into a feature length script. The character of Katherine Blair was entirely created, but her inclusion in the story is so appropriate and perfect to the events unfolding, as well as her serving as a perfect foil to Dees, that it never feels forced or long-winded. The ending sequence I spoke of earlier, too, is a creation on Pavia's part. Much of the dialogue remains the same, however, as well as the tense relationships—although it would seem Pavia's Dees comes across as a bit more sympathetic than King's.

Word on the street is Pavia has a new King project in the works…something about an anthology. After the last five years of tepid, King-inspired films, this is something to be truly excited about.