Every once in a while, a genuinely great horror movie—one that would rightfully be considered a classic, had it gotten more exposure and love at the box office—makes an appearance. It comes, no one notices, and it goes. But movies like this are important. They need to be treasured and remembered. If intelligent, original horror is supported, then that's what we'll begin to receive, in droves. We need to make these movies a part of the legendary genre we hold so dear. Because these are the unsung horrors. These are the movies that should have been successful, but were instead ignored. They should be rightfully praised for the freshness and intelligence and craft that they have contributed to our genre.

So, better late than never, we’re going to celebrate them now… one at a time.

Dir. Jon Amiel

1995

Warner Bros.

United States

United States

Copycat had the extreme misfortune of being released in theaters the same weekend as the-perhaps-you’ve-heard-of-it David Fincher-directed powerhouse Se7en. The two films are quite thematically similar, each featuring a serial killer with a gimmick: the former is repeating famous serial killings from years past, while the latter is using the seven deadly sins as his guide when taking lives. While Sigourney Weaver will always be a cinematic legend, she was sadly no match for Morgan Freeman and the up-and-coming Brad Pitt that weekend at the box office. Because the cast and crew of Se7en now currently enjoy a higher level of fame than those affiliated with Copycat (Fincher would go on to direct Fight Club and The Social Network; screenwriter Andrew Kevin Walker would write Sleepy Hollow and The Wolfman), it’s easy to assume that one film is superior to the other – and you would be right…just in the wrong order. Copycat exceeds Se7en in every way possible—from the first frame to the last.

While Se7en begins with a gritty, artsy pastiche of trembling letters and icky gooey things, screaming to the audience, “Our movie is so fucked up, OMG, get ready,” Copycat, likewise, merely just begins…with a panning shot of college students lazing about on a beautiful sunny day. Layered over their laughter is the speech being given nearby in the school’s amphitheater by Weaver’s Helen Hudson—one detailing the 25 serial killers cruising for victims at that very moment. It’s a scary notion, and not much else comes from her speech to allay any fears.

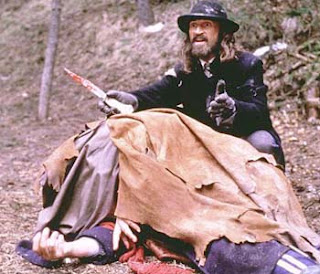

Helen Hudson is a serial killer specialist and she knows her shit, having written books on the subject, and even having testified in a trial against serial killer Daryll Lee Cullum (Harry Connick Jr., in a surprisingly effective performance rivaling Kevin Spacey’s own as John Doe.) Cullum isn’t all that happy about Helen’s testimony, and he lets her know that; after having escaped from prison, he stalks her to the college where she is giving her speech and attacks her with a metal zip line noose and scalpel. Helen survives the attack – the same can’t be said for an unfortunate cop – and months later, she is an agoraphobic, unable to set foot even three feet out her front door without suffering a panic attack. Having become a total recluse, she has sworn off the entire outside world, and the world of serial killers with it…until the headlines in the newspaper begin—headlines warning of a possible serial killer haunting the San Francisco area (a fitting place, being that San Fran was previous stalking ground for the Zodiac, a serial killer never caught).

Inspectors Monahan (Holly Hunter) and Goetz (Dermot Mulroney) are soon introduced as partners (and lovers?) in the homicide department of the San Francisco Police. The two achieve an instant level of believability thanks to their onscreen chemistry, and both give career-best performances. They soon become entangled with the psychologically damaged Helen Hudson, who after seeing the headlines in the papers, can’t help but call the homicide department with frustrated tips of the trade. While the two inspectors are stuck following up on Helen Hudson, their colleagues show their distaste for the woman in different ways: fellow officers make jokes at her expense, referring to her “lunar cycle” theory as the “moon bike,” while their superior, Lieutenant Quinn, refers to her as “the shrink who got the cop killed.” Clearly Helen Hudson’s relationship with San Francisco PD is not a stellar one.

Inspectors Monahan (Holly Hunter) and Goetz (Dermot Mulroney) are soon introduced as partners (and lovers?) in the homicide department of the San Francisco Police. The two achieve an instant level of believability thanks to their onscreen chemistry, and both give career-best performances. They soon become entangled with the psychologically damaged Helen Hudson, who after seeing the headlines in the papers, can’t help but call the homicide department with frustrated tips of the trade. While the two inspectors are stuck following up on Helen Hudson, their colleagues show their distaste for the woman in different ways: fellow officers make jokes at her expense, referring to her “lunar cycle” theory as the “moon bike,” while their superior, Lieutenant Quinn, refers to her as “the shrink who got the cop killed.” Clearly Helen Hudson’s relationship with San Francisco PD is not a stellar one.

Lastly, we have the titular serial killer Peter Foley (William McNamara), plumbing the depths of history for the perfect murders to recreate. McNamara has the hardest job in the film—to play not a “scary” serial killer, but a real one. And what do people always say about serial killers? “He seemed so nice and quiet; always kept to himself.” McNamara is a handsome, but plain looking fellow, and he works very hard to have a commanding presence onscreen. It comes dangerously close to not working at times, but he manages to pull it off. And going further with this idea of the guy next door being a serial killer, the movie cleverly shows you Peter several times during the movie—though never introduces him as a named character for that “Oh man, HE’S the killer!” shock ending. His unnoticed presence drives the point home: he’s been around since the first minute of the film and he was never noticed. He stood in the police station and watched as crackpots confessed to the murder HE committed, even smiling to himself…even saying hello to one of the detectives working the case. This is the point of the movie: Violence exists in our society and we like to think it wears a noticeable face and a sign on its back—that we know where it originates, what the causes are, and how to stop it. But the truth is, we don’t. The violence we live with every day doesn’t exist on the news or in the papers—it lives next door. It wears glasses and tends to a needy girlfriend and says hello when you pass by.

Helen Hudson is Weaver’s absolute best performance to date—she is a character truly damaged by her encounter with the very thing by which she was fascinated. And she did not bounce back like most horror/thriller movie heroines tend to do; instead she has been changed for the worst. While she, Monahan, and Goetz hunt for the serial killer plaguing the San Francisco streets, Helen Hudson is also hunting for the strength within herself to defeat the demons keeping her captive in her own home—she just doesn’t know it at the time.

Interestingly enough, the movie is also viewed as a pro-feministic one, being that the intelligence and the cunning come not from a generic male lead who lets his gun do the talking, but rather two women who have their own drama bubbling just under their surfaces. I say “interestingly” because earlier drafts of the script had Holly Hunter’s role written for a man, who was then supposed to go on to have a quasi-romance with Weaver’s character. The change was for the better, as it helped bring a fresh perspective to an overdone dynamic.

Copycat was written by Ann Biderman, who would go on to write the immensely twisted Primal Fear, as well as find great success in creating the cult hit police drama "Southland." Director Jon Amiel would later direct the crowd pleasers – if not box office/critical sensations – Entrapment and The Core. Composer Christopher Young turns in one of his best scores to date—an amalgamation of hushed chorus, dreamy, almost shallow pond water-like melodies, mixed with the harsh strings we’ve all come to expect from the horror/thriller genre.

Copycat is a masterful thriller, and though it’s not a bloody show like some of its genre colleagues, not everyone makes it out of the film alive—especially those whose deaths you won’t see coming. It doesn’t need a head in a box to be memorable, and it doesn’t need horrific set pieces filled with mutilated people. It only needs to be, because as it stands right now, it’s perfect.

Copycat is a masterful thriller, and though it’s not a bloody show like some of its genre colleagues, not everyone makes it out of the film alive—especially those whose deaths you won’t see coming. It doesn’t need a head in a box to be memorable, and it doesn’t need horrific set pieces filled with mutilated people. It only needs to be, because as it stands right now, it’s perfect.