Ravenous is an interesting first choice for what I hope to be a reoccurring column, because its score flies in the face of perhaps the oldest and still ongoing of debates: Does a musical score exist only to serve the images flashing on the screen, or should this same musical score also serve its own function and be just as effective, entertaining, and well-constructed, while playing independently of that image? Meaning, the scores for films like There Will Be Blood and Sinister are incredible in the way that they make the on-screen images ten times more effective…but can you listen to them independent of their respective films and still find them to be just as effective? And should it even matter if they simply don’t work on their own, given they were never supposed to be anything other than a companion to their film?

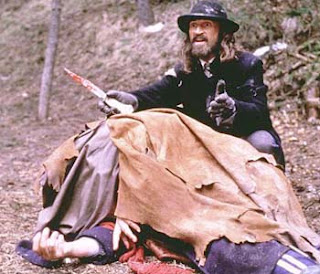

Ravenous seems to be gunning for the latter – that this film score exists only to serve this story of soldiers falling victim to a maniacal cannibal in the dead of winter during the mid-1800s. The Mexican-American War is in full swing, and soldiers are stationed at Fort Spencer to be on hand should their services be required. They spend their days getting high, writing music, or screaming in rivers, and seem to be risking death via total boredom until a stranger named Colqhoun arrives near dead from exposure. Once cared for, warmed, and given proper nourishment (heh), he rattles off his terrifying tale of being trapped in the woods and being forced to rely on cannibalism to survive. Everyone hearing the tale seems to instantly believe the stranger except Boyd (Guy Pearce), who finds the stranger to be more than a little suspicious.

Then a bunch of dudes get eaten!

(For a more in-depth breakdown/examination of Ravenous, read its Unsung Horrors entry. Sadly, its director, Antonia Bird, left us this year.)

The score by composer Michael Nyman and singer/songwriter/record producer Damon Albarn is wonderfully eclectic and quirky, as well as traditional and fucking eerie. Nyman has been composing for over forty years, though his name might not sound familiar outside of cult-like film-score devotees. He rarely scores anything outright “Hollywood” and opts to work in more classical environments. So it’s only natural he would bring with him less traditional ideas – and it’s those unusual ideas that begin the official soundtrack release.

(Note that I’ll only be highlighting the tracks I consider to stand out from the rest.)

“Hail Columbia,” the first track, is based on a pre-existing arrangement, but one that Nyman re-orchestrated specifically for Foster's Social Orchestra. This is important to mention because this orchestra is comprised of non-musicians, meaning the music as played sounds mostly sure-footed, but shaky and awkward. It certainly doesn’t sound polished. This odd approach was also used for “Welcome to Fort Spencer,” probably the least confident and most shakily recorded track in the batch. It literally sounds as if a group of musicians two weeks into their instruments are assembling and playing in a group for the first time. You might wonder why one would bother with such an approach – why purposely include awkward or even terrible sounding music? Because there’s no better way than painting the military as clumsy and primitive; and the inhabitants of Fort Spencer fare even worse. This track, filled with horn squeaks and screechy strings, make these men seem like miscreants, degenerates, and completely unrefined. Rather than having the men themselves do and act in a manner that screams “idiot,” instead let the music do that for them. “Noises Off” is the final track to take this approach – all the usual out-of-tune notes are in attendance, but also seems to have been recorded at far slower than was intended, making it seem even less confident.

If “Hail Columbia” was the first of a three-part series featuring unsure players, “Stranger in the Window” would be the first of several tracks to drop the altogether dopy and amusing sound and instead go for one ominous and foreboding. The music up to this point has been either goofy or non-threatening. “Stranger in the Window” plays as Colqhoun makes his first appearance – right off you should know there’s something not right about him.

“Boyd’s Journey” and “Colqhoun’s Story” have been credited to Albarn without question. Here, and in some of his other contributions, the musician incorporates found audio, recordings from scratched vinyl records, and vintage field recordings into his original compositions. The latter track repeats one measure of what seems to be an old jaunty tune that likely sounded much more jolly in its original incarnation. Here, though, it provides the syncopation on which Albarn builds his ideas – none of them jolly. I love music that starts small with a simple pattern and builds, and continues to build, adding more instrumentation and ideas until it seems unrecognizable from when it first begin. “Colqhoun’s Story” delivers this in spades.

“Wendigo Myth” is one lone voice performing a Native American vocalization. I personally know nothing about this track or its lineage, but I’d love to know how it was captured. Was a vocalist brought in to record in a studio? Was it recorded in the field? The sound quality isn’t quite 100%, as it’s slightly echoey and tinny. I prefer to think this was recorded in the wild, but maybe because that’s the more interesting and romantic option. [Update: IMDB confirms: Milton 'Quiltman' Sahme's chant was recorded by Damon Albarn in Quiltman's living room on the reservation. Albarn was referred to Quiltman by Joseph Runningfox.]

Following “Trek to the Cave,” “He was Licking Me” will easily get under your skin. A more straightforward composition (by which composer I’m not sure), it’s likely the most brooding track. It’s something Wojciech Kilar would have composed for his take on Bram Stoker’s Dracula. “The Cave” seems to be full on Albarn, utilizing repeating musical stings, unsure drum beats, a Glockenspiel (of all things), and something very non-instrumental also sounding off in the background. Soon these sounds fade into an elongated string punctuated every so often by a single piano key. It transforms very quickly from something unusual (while the soldiers are still outside the cave) to something incredibly suspenseful (after they enter), and into a full-on sprint (once Colqhoun enacts his savage plan). Running over seven minutes, “The Cave” transforms and mutates more than any other track, especially at 4:15 when those drums mercilessly kick in. It then becomes a whole other beast entirely. “The Cave,” to me, sums up Ravenous’ entire soundtrack: It’s a bevy of different ideas that one would think could never work, but somehow all comes together and provides something special and unforgettable.

“Run” is the only track which can boast that it sees to fruition the film’s sudden tonal shift from utter terror to (temporary) hillbilly humor. It’s at this moment when Colqhoun flicks his fingers at one of the surviving soldiers (not many are alive at this point) and tells him, simply, to run. Had this scene been scored by something terrifying filled with screeching strings, Colqhoun’s cat-and-mouse games would have seemed disturbing and psychotic. But instead, mixed with hillbilly hooting and fiddle, it actually becomes a little hilarious, and we realize that, for Colqhoun, this is nothing but a good time.

I love a good track that gets the adrenaline pumping, and “Let’s Go Kill That Bastard” kills it. The pounding drums and fiddle remain consistent, but the other instruments come and go, so the song is constantly changing its sound. If there were any track I would listen to on repeat, it’s this one (and I have).

“The Pit” at times seems like it should belong in a Disney film, not in an extremely bloody gore-fest black comedy about cannibals. Harps, swelling strings, and female ululations will make you wonder if Boyd, following his crushing plummet from the cliff, is actually dreaming. He’s not, though. Instead, he’s eating Neil McDonough.

If Ravenous were to have a “theme,” I suppose it would be “Manifest Destiny.” This track manages to encapsulate all the music we’ve heard – and well as the different interpretive approaches – while creating a new musical composition. Like in the earlier track I praised, the track starts off simply and then builds and builds.

“Saveoursoulissa” is the longest track – as well as the eeriest –in this whole thing: repeating discordant notes on a scratchy record, pounding drums, warbling electronic noises, moaning vocalizations. And that’s just the first two minutes. This track goes on for a staggering 8:43, and never sounds like anything other than a nightmare. If you’re a horror writer, play this track in the background during your next writing session. Your imagination will end up places you never thought you’d go.

“End Titles” is a reprise rendition of “Boyd’s Journey,” which is fitting, being that since Boyd is currently pinned to Colqhoun in a bear trap and is slowly bleeding to death, he’s about to begin a new journey: either to death, or to his rebirth, as he ponders Colqhoun’s final words: “If you die first, I’m definitely going to eat you. But the question is…if I die first, are you going to eat me?”

So…having said all of that, what’s the verdict for Ravenous? Is it something only to be appreciated alongside the film, or can it be enjoyed solo? The answer is: both. At least it is for me. Maybe it’s because I’ve seen Ravenous countless times and count it among one of my favorites, so some images that certain portions of score are married to are fresh in my head. Yeah, I might skip the Foster's Social Orchestra tracks, but the rest of this stuff is bloody good.