Jan 24, 2020

Jan 23, 2020

DEMON WIND (1989)

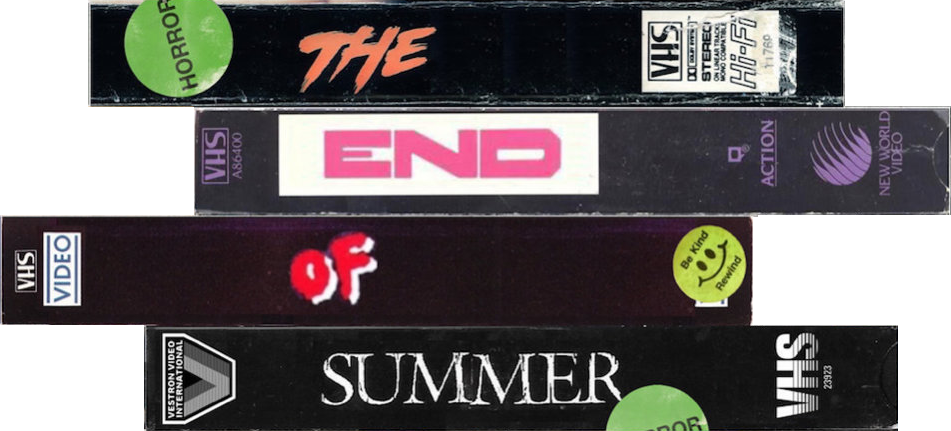

I have to wonder why films like Night of the Demons and House are so celebrated, but meanwhile, Demon Wind has remained so obscure. Every bit as silly, gory, teen-douched, and well-intended as those other titles, it should have been destined for the same kind of infamy and video store-stoked adoration. It scratched that VHS-era itch with all the usual stalwarts one would come to expect from the genre: ghastly effects, over-the-top gore, hapless teens in peril, a dash of nudity, and skeletons.

For fans with a love for Night of the Demons or Demons/Demons 2, Demon Wind could be the newest love of your life, thanks to its practical effects, rubber and foam monsters, and lots and lots of blood and goo.

Demon Wind is made with the same kind of authenticity as the original Evil Dead while also borrowing a little of its aesthetic. (And plot.) (And tone.) (And look.) To call it a bold-faced ripoff might be taking things a bit far, but I’d feel pretty confident in saying that Demon Wind probably wouldn’t exist without The Evil Dead. It balances the horror and the drama in the same way, striving to concoct legitimately eerie imagery without the foresight to know that while the filmmakers were hoping to create things from your deepest, darkest nightmares, they were instead creating something that’s going to look just a touch silly.

You pretty much know the caliber of acting you’re going to get with a production of this size (read: not big) and the sub-genre in which Demon Wind exists (read: rubber monsters), but again, this only adds to the flavor of the film’s overall experience. Your lead hero, Cory (Eric Larson), looks uncannily like Emilio Estevez and coincidentally brings about the same kind of sincerity, even doing better here than Bruce Campbell did during his own maiden descent into demonic territory. Everyone after that exists on a sliding scale, with some performances ranking very below average.

Amusingly, Demon Wind just keeps introducing teen characters to the conflict, and after having digested enough of these kinds of films from this era, you can’t help but smile because you know every single one of these kids are going to die gloriously. Even as Demon Wind begins to run out of demon fodder halfway through, it introduces two more characters who were “late” following Cory’s initial invitation and who don’t last for too long once they get out of the car. (Also look for an early-career appearance from Lou Diamond Phillips as one of the many demons.)

Amusingly, Demon Wind just keeps introducing teen characters to the conflict, and after having digested enough of these kinds of films from this era, you can’t help but smile because you know every single one of these kids are going to die gloriously. Even as Demon Wind begins to run out of demon fodder halfway through, it introduces two more characters who were “late” following Cory’s initial invitation and who don’t last for too long once they get out of the car. (Also look for an early-career appearance from Lou Diamond Phillips as one of the many demons.)

If you’re the kind of person who used to wander up and down the horror aisle of the video store during the golden VHS era but Demon Wind has somehow evaded you all these years (as it did me), rectify that. It’s the kind of silly but imaginative (and gory) horror flick you would have stayed up late to watch with friends once your parents had gone to bed. One could never reasonably call Demon Wind good but it is fun, and when you’re dealing with a horde of zombies and animated cow skulls and succubi that leave nothing to the imagination, that’s all you could ever ask for.

Jan 22, 2020

Jan 21, 2020

SHOCKER (1989)

It's been just under five years since Wes Craven's death and it still feels very surreal and wrong that he's gone. On that sad evening in August, the news of his death began circulating throughout the web, especially on social media, and people were sharing their surprise and dismay that the man who had created so many nightmares (literally and figuratively) for legions of moviegoers was gone. Memorials and tributes began cropping up all over the place to examine the man's legacy, his fingerprints on the horror genre, and the films he left behind.

It's a strange, strange feeling to have experienced such a loss for someone many mourners never knew personally, but yet at the same time felt like family. How is that even possible? How can a perfect stranger, who did nothing more than create a handful of boogeyman and rob us from a few nights of sleep, leave a friend- or family-sized hole behind in the wake of his death? Because, for the horror genre, he's been an ever-constant presence in our homes. It was through his sensibilities as captured on film with A Nightmare on Elm Street or The Hills Have Eyes, or any number of documentary-driven examinations on horror in which he eagerly took part, that he became so well known to us all. There was no mistaking that soft-spoken voice, that kind and somewhat shy smile, and his incredibly nuanced and levelheaded approach to the genre, and why it was important.

In the fantastic horror documentary The American Nightmare, Craven had said:

“[Horror films are] boot camps for the psyche. It’s strengthening [kids’] egos and strengthening their fortitude… That’s something the parents never seem to think about… Even if [the films] are giving them nightmares, there’s something there that’s needed.”In a really strange way, Craven became a father to us all - concocting on paper and then on film an array of boogeymen to scare us to our wit's end, not just so we could leave the theater laughing at the rush only a horror film can bring, but to prepare us for the real world...where things are much scarier, and much more dangerous.

In the days following his death, there was an appropriate amount of people who openly mourned, but there were also a faction of those who stated, unromantically, "Wes Craven actually made a lot of bad movies." And maybe that's true. Maybe many, or most, of Craven's films never managed to reach the scare-tinged heights of A Nightmare on Elm Street, the clever ingenuity of Scream, or the naked and honest brutality of The Last House on the Left, but no director on earth - living nor dead - is free of their own collection of mediocrity. One of the most celebrated genre directors ever to have lived, a man named Hitchcock, was not even free of such infallibility, and when he died, no Internet armchair critic was opining about all the bad films he made.

Which leads us, perhaps unceremoniously, to Shocker.

To call Horace Pinker a cheap Freddy Krueger re-appropriation wouldn't be a slight against the departed Craven, who has freely admitted over the years that his signing away of all rights to A Nightmare on Elm Street (which, in case you didn't know, generated enough money, along with its subsequent sequels, to establish the studio that would then go on to produce the Lord of the Rings trilogy) directly led to Shocker, in hopes that Craven could shape a new movie maniac with enough familiarity that it would create its own franchise which he could then control (and profit from).

That did not happen.

Man who comes out of your TV was no match for man who comes out of your nightmares.

Taken on its own merit, Shocker is very okay, if at times a little too silly, with an electric! (ugh) performance from Mitch Pileggi. Craven has always tried to mix humor into his horror films, and while this has often worked (Scream), other times the two very conflicting tones just don't work well together (Last House). For something like Shocker, in which a discorporated serial killer can travel through electrical circuits and end up on television shows, yeah, humor was to be expected. A silly movie would look even sillier if there wasn't a sly sense of humor throughout the whole thing.

Though you may not be able to tell by the finished product, Shocker was based on several distinct inspirations, from other films to Craven's own personal life. The construct of the film was inspired by a combination of 1951's The Thing From Another World and 1987's The Hidden, directed by Jack Sholder...who, quite ironically, had directed 1985's Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy's Revenge. Personally, Craven has previously noted the tense relationship he had with his father, whom he described as "angry," and how the making of Shocker was an exorcism of sorts for his feelings toward him. Of the scene where Michael Murphy's recently possessed character tries to convince his son (Peter Berg) that he's fine, and that he's taken control, only to reveal that it was Pinker all along, Craven chuckled and observed, "I dunno, I guess I have trust issues."

The most striking thing about Shocker is how very similar it all plays out to A Nightmare on Elm Street - so much that Craven, while viewing the film for the first time since its post-production, admitted to being taken aback by all the similarities.

Shocker isn't a "great" addition to Craven's filmography, but in an odd way, it is essential viewing, if only to see a filmmaker retreading familiar ground in a different environment simply because that's where his sensibilities led him. However you may feel about Shocker, it's a pure, unfiltered Wes Craven film. And it's worth seeing for that alone.

Celebrate the catalogs of those filmmakers you revere. Lesser entries still have a lot of merit, and much to offer to completist viewers. Though it will never be spoken about with as much reverence as A Nightmare on Elm Street, Shocker very much contains Craven's aesthetic and sensibilities in every frame - not just in the usage of the dream relationships and walking premonitions, but in the power of the youth who are unable to depend on the nearest adult and have no choice but to take care of it themselves.

Father to us all, indeed.

Rest easy, Professor Craven. You are still very missed.

Jan 20, 2020

Jan 19, 2020

LEATHERFACE: THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE III (1990)

Like a few other horror franchises, the Texas Chainsaw Massacre series keeps on truckin’; a new entry is released every few years, with the most recent being 2018's Leatherface (confused yet?). Following the wonderful and visceral original, subsequent entries were all over the place in terms of quality. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (1982) and Return of the Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1994) were completely insane. 2003's The Texas Chainsaw Massacre remake returned things to respectability, insofar as a Chainsaw movie could be, but the entries that followed, again, got worse and worse.

And meanwhile, sitting quietly in the corner, is 1990’s Leatherface: Texas Chainsaw Massacre III, the most middle-of-the-road film in the series, and the first to be released by a major studio...so you know what that means: studio interference and MPAA ball-breaking. Video editions of the sequel sport the “unrated” cut, restoring some of the grue and gore that was originally shot by director Jeff Burr that was then removed following a battle with the MPAA, although awkward edits that cut away from the violence suggest an even more violent version that has yet to the light of day. Famously, Leatherface: Texas Chainsaw Massacre III features Viggo Mortensen in one of his earliest roles, and he's spoken candidly in the past about his work on the movie as well as its final iteration seen by audiences:

“[Shooting that movie] was fun. I don’t know how many times they sent that to the censors … They kept getting X’s and so they cut so much out that I think the movie is only like 70 minutes long. Unfortunately most of the really funny jokes were associated with gruesome bloodletting of some kind or another.” (Source: Carpe Noctem Magazine). “The movie company got cold feet and cut away the most terrifying and gruesome scenes, and it ended up being a rather incoherent movie.” (Source: M/S Magazine).

Despite Mortensen’s misgivings, Leatherface: Texas Chainsaw Massacre III, in its "unrated" form, is a perfectly acceptable entry in the chainsaw-wielding series, though except for adding a pint-sized kid to the Sawyer clan and a survivalist into the mix, it doesn’t try anything new. Burr, however, definitely gets points for casting horror-friendly actors, including William Butler and Jennifer Banko from Friday the 13th: Part VII — The New Blood, Ken Foree from Dawn of the Dead, and Mortensen, who at that point had done Renny Harlin’s Prison and the thriller Tripwire. Adding to that, Burr’s level of mayhem and bloody violence is admirable and appreciated, as is the blackest of black humor lifted from the original (and skipped by its sequel in favor of broader stupidity). Where Leatherface: Texas Chainsaw Massacre III lacks is through its somewhat meandering pace (a LOT of time is spent with our characters wandering around the Texas woods) as well as its closeness to the original’s plot, which prevents it from establishing more of an identity.

Burr follows the “if it ain’t broke” mentality, but by doing so, he’s only further welcoming comparison to Hooper’s seminal original, at which point Leatherface: Texas Chainsaw Massacre III doesn’t stand a chance. This isn’t necessarily his fault, as original distributor New Line Cinema had acquired the Chainsaw rights from Cannon Films in hopes of softly rebooting the series and creating a new direction where Leatherface would be its prominent boogeyman, similar to their very successful Nightmare on Elm Street series (hence the titular madman being called out in the title). That at least explains why Leatherface: Texas Chainsaw Massacre III feels like a loose remake, although the dismal box office return put New Line’s plans on the back burner for several years. It’s also a little odd that New Line’s desired to make Leatherface more prominent a la Freddy Krueger, being that he has no more or less screen time here than he did in the original film. By comparison, Mortensen’s “Tex” gets way more to do. (I’m also trying to figure out where all these additional family members keep coming from. Are they actually related to Leatherface, or just a bunch of random Texan psychopaths who somehow found each other in the age before Craigslist? If they’re actual relations, where the hell were they during Dennis Hopper’s duel-chainsaw smackdown at the end of the previous sequel? Were they on vacation, or at mass? How do they multiply? Are they the products of inbreeding? What the hell goes on in the backwoods of Texas, anyway?) (I have to sit down.)

Leatherface: Texas Chainsaw Massacre III, despite the obviously tacked on ending, and that its “unrated” form still seems toothless at times, is a decent sequel and worthy of appreciation...only when looking at the other sequels. After seeing how off the rails the series eventually goes, Leatherface: Texas Chainsaw Massacre III might even now be considered a high point — depending on who’s looking.

Jan 18, 2020

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)