Scarecrows have become infamous iconography of Halloween, though as far as I know, there are no myths about scarecrows that concern our favorite day of the year, and their history don’t lend themselves to such a connection. Perhaps we can thank Nathaniel Hawthorne’s 1852 short story “Feathertop,” about a scarecrow brought to life by a witch in Salem, Massachusetts. Their connection to farmland and harvest (and hence, autumn) could argue for their association as well. But regardless the link remains and I’m cool with it, because they make a fine addition to a fine holiday. Go to any Halloween party store and you’re likely to find a scarecrow mask or costume, or even a decapitated and blood-dripping scarecrow head. (Don’t think about that one too long, or you’ll ruin the fun.)

Sadly, scarecrows are slowly being phased out of regular usage, as farmers are opting to instead use wooden silhouettes of large predatory creatures or even beach-ball-shaped contraptions that do god knows what, but do apparently scare away birds. More effective they might be, they are certainly less interesting.

The scarecrow has been used only moderately throughout horror cinema, which is a shame, because their visage is effortlessly creepy and could make for a good on-screen threat given the right approach. Unfortunately, most of the scarecrow’s voyage into celluloid have resulted in count-them-on-one-hand entries actually worth your time. 1990’s

Night of the Scarecrow is a fun and low-budgeted little thriller featuring a very young and beardless John Hawkes; 1988's

Scarecrows is a flat, though sometimes bizarre, offering; 2011’s

Husk is a decent time-waster that gets more right than it does wrong. And the less said about the direct-to-video

Scarecrow Slayer series, the better. But 1981’s

Dark Night of the Scarecrow will likely always reign supreme. Recently resurrected for an unexpected video release in 2010, and nearing the end of its license before it goes back out of print,

Dark Night of the Scarecrow,

for decades, belonged to that dubious club of horror films that continued to live on after their first theatrical or television appearance through bootleg networks. Following a 1986 VHS release (and going out of print soon after), legitimate copies of the film were nigh impossible to track down. It was one of those movies that risked being lost with time. But, as any loyal horror fan will do when denied their white whale of a film, they set out to horror conventions or to the many websites specializing in unavailable or never released films to secure themselves a copy likely created from a 37th generation VHS tape.

When the legitimate release was announced in 2010, I wasted no time in snapping up myself a copy. After all, I had heard nothing but praise for the film for many years, and having a rough idea what it was about, I was incredibly interested and excited to give it a watch. About scarecrows, set on Halloween, and allegedly scary. Of course I was all over it. After all, the quote from Vincent Price proudly blazed across the front – “I was terrified!” – was quite possibly the only marketing a horror film would ever need.

My copy soon arrived and I saved it for near-Halloween. And I watched.

And though I found the film to be well made and well acted, I was surprised by how…uninvolved in the story I found myself. And I was a little disappointed in another regard: the lack of scarecrows. I was expecting to see that infamous canvas-bag face sitting atop the shuffling straw-filled figure as it chased down its victims one by one. But that didn’t happen. In fact, the lone scarecrow remains limp and still for pretty much the entire running time – and is only on screen for about five minutes.

I remember at the time chalking it up to just yet another film I had lost to the hype machine, as nothing could have lived up to the years and years of folks saying they recall having watched it when it aired on television and how scary it was, etc., etc.

But something unexpected happened: though I thought the film was reasonably good, I held onto it. (This is important to note, as I was once an avid collector of films, CDs, and books, and would immediately get rid of anything I felt wasn't worth keeping.) And in the days following my first viewing, I found myself thinking back on the film, as it had somehow stuck with me. So, a few weeks later, I watched it again.

And I

got it.

I saw what the big deal was and this time I simply allowed myself to be taken away by the story.

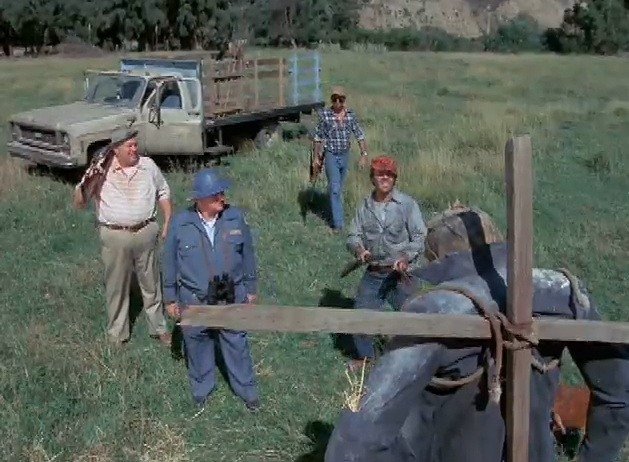

In a nameless mid-western town, a young girl named Marylee Williams and a simple-minded man named Bubba Ritter (Larry Drake) play together in the middle of a field. These two are good friends – have been for some time – and this really bothers a few townspeople, namely Otis (Charles Durning), Skeeter (Robert F. Lyons), Philby, (Claude Earle Jones), and Harliss (Lane Smith). He and his cohorts believe that Bubba is potentially dangerous and perhaps even a pervert, and such should not be allowed near any young child. "He's a blight...like stink weed and cutworm that you spray and spray to get rid of, but always keeps coming back," Otis seethes. "Something's got to be done...but it has to be permanent."

While harmlessly sneaking into a backyard to play with a decorative garden fountain, a dog viciously attacks Marylee and Bubba manages to save her. She is brought to the hospital bloodied and unconscious and Otis naturally assumes the worst. He gathers up his hateful posse and heads out to the Ritter farm to exert some private justice.

Bubba’s mother (Jocelyn Brando), having hidden her son within the scarecrow poled in their back field, forbids the men from entering the house. She attempts to lie and says Bubba is nowhere on the property, but the men know better. They instead begin their search outside, and through the holes on the scarecrow’s burlap-sack face, Otis sees Bubba’s terrified eyes. The men open fire, killing Bubba with an obnoxious amount of bullets. Then they find out the truth – that Bubba hadn’t been the one who hurt Marylee at all, but had actually saved the girl’s life from what everyone learned was a dog attack. Otis places a pitchfork in the dead Bubba's hand, his mind already piecing together a possible way out of trouble. An eerie wind picks up immediately after...announcing a vengeance soon to come.

Otis and his posse are tried for Bubba's murder (rather quickly), but they claim self-defense, and because the prosecutor can present no witnesses and no evidence, the men find themselves free – at least from the courts. Having just gotten away with murder, the men are feeling pretty good. But then each of the men begin seeing the Ritter farm scarecrow – the same one in which Bubba had attempted to hide – planted in the middle of their own fields. And then the men are picked off one by one by an unseen killer in the order following their visitation by the scarecrow, as if someone were taunting them…or letting them know who would be next.

There are plenty of red herrings provided to us. The killer could be anyone: Bubba's mother, who in a fit of rage loses her mind and begins tracking down the men who killed her son; or perhaps it's District Attorney Sam Willock, who tried to prosecute the men and was nearly thrown back in shock when they were set free; it could even be one of the men responsible for Bubba's death, buckling under the simmering guilt he has successfully hidden away from his friends.

Or perhaps it's the ghost of Bubba himself, back from the grave to take his revenge on the men who took him away from his mother and his only friend...

A friend of mine was killed the other night.

So I heard.

They all think it was an accident. I don't.

There's other justice in this world.

Besides the law?

It's a fact. What you sow, so shall you reap.

Dark Night of the Scarecrow is intelligently engineered so

that our antagonists suffer for pretty much the entire film. Though they

begin to succumb to the fear of their being murdered, and are haunted

by the harbinger of doom that is the Ritter farm scarecrow, they never

show regret. They never break down and say, “Oh, I wish we hadn’t killed

that poor man!” And because of this, we watch without conflict or guilt

as each of the men are hunted down. We pity none of them are they are

each killed on their own farms in the middle of the night. We certainly

don't pity Otis, as the film bravely dedicates much of its time with

this man who is seemingly willing to do anything to save his own

skin…and is very willing to kill again. It is a very bold move to have

your audience spend the majority of the film following around a

completely despicable character. After all, we’re never going to pity

him, or show him our sympathies – there will be no catharsis for him –

so in the interim until his inevitable fate, we will enjoy watching him

squirm. His death, for us, will be a release – especially when young

Marylee finds herself in peril once more.

There’s no reason at this point to reaffirm Charles Durning as one of

the greats (RIP, sir), but I’ll reaffirm, gladly. At this time in his

career, Durning was enjoying himself in little thrillers like this, as

well as

When A Stranger Calls and

The Final Countdown, and

he was certainly open to taking on the role of Otis, a complete

scuzzball in every sense of the word. He’s an unapologetic murderer,

this we know, and an insensitive asshole who doesn’t know when to quit

as he takes it upon himself to begin harassing Bubba’s mourning mother,

whom he assumes is behind the tragedies befalling his fellow vigilantes.

But he’s also something else, too. Though the film does a very good job

of straddling this fine line, it’s very carefully intimated that Otis

is a pedophile. He’s a single male, one among many in the boardinghouse

where he lives, and the earlier scene with Otis and

Mrs. Ritter confirms as much, as she tells him she knows

"exactly what [he is]. This is a small town. Everybody talks.”

This,

frankly speaking, was a fucking ballsy move to impart on this otherwise

straightforward ghost movie (made for television, no less). It also

adds a very seedy new layer: Perhaps Otis hadn’t so impulsively killed

Bubba simply because the man-child’s friendship with Marylee disgusted

him. No… perhaps Otis was jealous, even being… territorial.

Gross.

Larry

Drake’s screen time as Bubba is understandably limited, as he’s shot

full of holes within the first twenty minutes, but it’s nice to see him

play a simple and innocent character like Bubba Ritter. He is so

ingrained in our minds thanks to his villainous turns in

Dr. Giggles or the

Darkman

films that typically our only affiliation we have with the man is being

a cigar-cutting or pun-hurling sociopath. To Drake's credit, it’s

always tough and potentially career-damaging to play a character with

developmental deficiencies, but Bubba really just comes across as a

child – easily prone to fear and shy around girls. He’s charming and

even cute – by design, as I’m sure the filmmakers wanted you to feel

especially angry towards the men who eventually take his life.

The film is very dissimilar from the previously mentioned

Night of the Scarecrow,

Scarecrows, and

Husk

– those films' directors were not afraid to make their straw-headed

killers vicious and violent. People are hacked apart, strangled, even

raped with penetrating straw spears. But in

Dark Night of the Scarecrow,

all the gruesomeness is left to your imagination. The men are killed,

oh yes, and in imaginatively painful ways, but never on screen. It is

old school in its execution because it

is old school. A swinging

shaded bulb complementing a man’s desperate screams is far more

affecting than a man being folded in half by random farm equipment

front-and-center on screen.

Despite the obvious constraints of a television budget, director Frank De Felitta (

The Entity)

shows real skill and creativity. The first scene of the ghostly Ritter

farm scarecrow stuck into Harliss' field is captured in one extreme long

shot, making the scarecrow barely visible, yet still unnerving and

nightmarish. But the second sighting in Philby's field is perhaps

better; we see the man looking horrified at something off-screen and in

the distance, and he begins to run towards it. Finally he falls to his

knees as the camera pulls back...and reveals the scarecrow.

Stationary bird scarers have never been creepier.

De

Felitta also knows how to use the quiet mid-western night to maximum

effect. What should be peace and solitude is instead interrupted by the

humming of machinery kicking on by itself, or the squealing of disturbed

pigs, or the crunching sound of methodical footsteps. It's classy yet

familiar, yet also entirely effectively.

Honestly, the film is smart enough to know all it needs to be scary is this: