"When Michael Myers was six years old, he stabbed his sister to death. He was locked up for years in Smith's Grove Sanitarium, but he escaped. Soon after, Halloween became another word for mayhem... If there's one thing I know, you can't control evil. You can lock it up, burn it and bury it, and pray that it dies, but it never will. It just... rests awhile. You can lock your doors, and say your prayers, but the evil is out there... waiting. And maybe, just maybe... it's closer than you think."

Oct 17, 2013

#HALLOWEEN: YOUR FINAL SACRIFICE

Oct 16, 2013

#HALLOWEEN: UNSUNG HORRORS: DARK NIGHT OF THE SCARECROW

Every once in a while, a genuinely great horror movie—one that would rightfully be considered a classic, had it gotten more exposure and love at the box office—makes an appearance. It comes, no one notices, and it goes. But movies like this are important. They need to be treasured and remembered. If intelligent, original horror is supported, then that's what we'll begin to receive, in droves. We need to make these movies a part of the legendary genre we hold so dear. Because these are the unsung horrors. These are the movies that should have been successful, but were instead ignored. They should be rightfully praised for the freshness and intelligence and craft that they have contributed to our genre.

So, better late than never, we’re going to celebrate them now… one at a time.

Dir. Frank De Felitta

1981

CBS

United States

"[I] seen it, Otis. The scarecrow. The same one. Bullet holes, everything. Just like before. Only now it was filled with straw."

"[I] seen it, Otis. The scarecrow. The same one. Bullet holes, everything. Just like before. Only now it was filled with straw."

Scarecrows have become infamous iconography of Halloween, though as far as I know, there are no myths about scarecrows that concern our favorite day of the year, and their history don’t lend themselves to such a connection. Perhaps we can thank Nathaniel Hawthorne’s 1852 short story “Feathertop,” about a scarecrow brought to life by a witch in Salem, Massachusetts. Their connection to farmland and harvest (and hence, autumn) could argue for their association as well. But regardless the link remains and I’m cool with it, because they make a fine addition to a fine holiday. Go to any Halloween party store and you’re likely to find a scarecrow mask or costume, or even a decapitated and blood-dripping scarecrow head. (Don’t think about that one too long, or you’ll ruin the fun.)

Sadly, scarecrows are slowly being phased out of regular usage, as farmers are opting to instead use wooden silhouettes of large predatory creatures or even beach-ball-shaped contraptions that do god knows what, but do apparently scare away birds. More effective they might be, they are certainly less interesting.

The scarecrow has been used only moderately throughout horror cinema, which is a shame, because their visage is effortlessly creepy and could make for a good on-screen threat given the right approach. Unfortunately, most of the scarecrow’s voyage into celluloid have resulted in count-them-on-one-hand entries actually worth your time. 1990’s Night of the Scarecrow is a fun and low-budgeted little thriller featuring a very young and beardless John Hawkes; 1988's Scarecrows is a flat, though sometimes bizarre, offering; 2011’s Husk is a decent time-waster that gets more right than it does wrong. And the less said about the direct-to-video Scarecrow Slayer series, the better. But 1981’s Dark Night of the Scarecrow will likely always reign supreme. Recently resurrected for an unexpected video release in 2010, and nearing the end of its license before it goes back out of print, Dark Night of the Scarecrow, for decades, belonged to that dubious club of horror films that continued to live on after their first theatrical or television appearance through bootleg networks. Following a 1986 VHS release (and going out of print soon after), legitimate copies of the film were nigh impossible to track down. It was one of those movies that risked being lost with time. But, as any loyal horror fan will do when denied their white whale of a film, they set out to horror conventions or to the many websites specializing in unavailable or never released films to secure themselves a copy likely created from a 37th generation VHS tape.

When the legitimate release was announced in 2010, I wasted no time in snapping up myself a copy. After all, I had heard nothing but praise for the film for many years, and having a rough idea what it was about, I was incredibly interested and excited to give it a watch. About scarecrows, set on Halloween, and allegedly scary. Of course I was all over it. After all, the quote from Vincent Price proudly blazed across the front – “I was terrified!” – was quite possibly the only marketing a horror film would ever need.

My copy soon arrived and I saved it for near-Halloween. And I watched.

And though I found the film to be well made and well acted, I was surprised by how…uninvolved in the story I found myself. And I was a little disappointed in another regard: the lack of scarecrows. I was expecting to see that infamous canvas-bag face sitting atop the shuffling straw-filled figure as it chased down its victims one by one. But that didn’t happen. In fact, the lone scarecrow remains limp and still for pretty much the entire running time – and is only on screen for about five minutes.

I remember at the time chalking it up to just yet another film I had lost to the hype machine, as nothing could have lived up to the years and years of folks saying they recall having watched it when it aired on television and how scary it was, etc., etc.

But something unexpected happened: though I thought the film was reasonably good, I held onto it. (This is important to note, as I was once an avid collector of films, CDs, and books, and would immediately get rid of anything I felt wasn't worth keeping.) And in the days following my first viewing, I found myself thinking back on the film, as it had somehow stuck with me. So, a few weeks later, I watched it again.

And I got it.

I saw what the big deal was and this time I simply allowed myself to be taken away by the story.

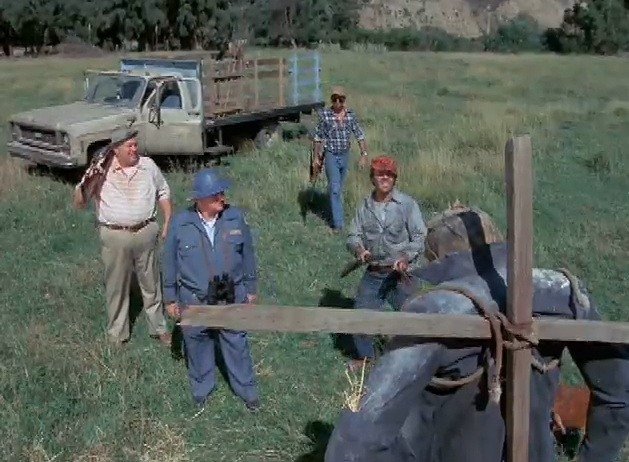

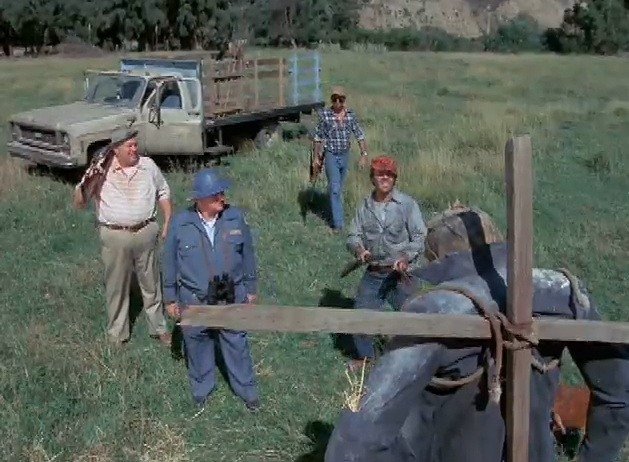

In a nameless mid-western town, a young girl named Marylee Williams and a simple-minded man named Bubba Ritter (Larry Drake) play together in the middle of a field. These two are good friends – have been for some time – and this really bothers a few townspeople, namely Otis (Charles Durning), Skeeter (Robert F. Lyons), Philby, (Claude Earle Jones), and Harliss (Lane Smith). He and his cohorts believe that Bubba is potentially dangerous and perhaps even a pervert, and such should not be allowed near any young child. "He's a blight...like stink weed and cutworm that you spray and spray to get rid of, but always keeps coming back," Otis seethes. "Something's got to be done...but it has to be permanent."

While harmlessly sneaking into a backyard to play with a decorative garden fountain, a dog viciously attacks Marylee and Bubba manages to save her. She is brought to the hospital bloodied and unconscious and Otis naturally assumes the worst. He gathers up his hateful posse and heads out to the Ritter farm to exert some private justice.

Bubba’s mother (Jocelyn Brando), having hidden her son within the scarecrow poled in their back field, forbids the men from entering the house. She attempts to lie and says Bubba is nowhere on the property, but the men know better. They instead begin their search outside, and through the holes on the scarecrow’s burlap-sack face, Otis sees Bubba’s terrified eyes. The men open fire, killing Bubba with an obnoxious amount of bullets. Then they find out the truth – that Bubba hadn’t been the one who hurt Marylee at all, but had actually saved the girl’s life from what everyone learned was a dog attack. Otis places a pitchfork in the dead Bubba's hand, his mind already piecing together a possible way out of trouble. An eerie wind picks up immediately after...announcing a vengeance soon to come.

Otis and his posse are tried for Bubba's murder (rather quickly), but they claim self-defense, and because the prosecutor can present no witnesses and no evidence, the men find themselves free – at least from the courts. Having just gotten away with murder, the men are feeling pretty good. But then each of the men begin seeing the Ritter farm scarecrow – the same one in which Bubba had attempted to hide – planted in the middle of their own fields. And then the men are picked off one by one by an unseen killer in the order following their visitation by the scarecrow, as if someone were taunting them…or letting them know who would be next.

There are plenty of red herrings provided to us. The killer could be anyone: Bubba's mother, who in a fit of rage loses her mind and begins tracking down the men who killed her son; or perhaps it's District Attorney Sam Willock, who tried to prosecute the men and was nearly thrown back in shock when they were set free; it could even be one of the men responsible for Bubba's death, buckling under the simmering guilt he has successfully hidden away from his friends.

Or perhaps it's the ghost of Bubba himself, back from the grave to take his revenge on the men who took him away from his mother and his only friend...

A friend of mine was killed the other night.

They all think it was an accident. I don't.

Besides the law?

Dark Night of the Scarecrow is intelligently engineered so that our antagonists suffer for pretty much the entire film. Though they begin to succumb to the fear of their being murdered, and are haunted by the harbinger of doom that is the Ritter farm scarecrow, they never show regret. They never break down and say, “Oh, I wish we hadn’t killed that poor man!” And because of this, we watch without conflict or guilt as each of the men are hunted down. We pity none of them are they are each killed on their own farms in the middle of the night. We certainly don't pity Otis, as the film bravely dedicates much of its time with this man who is seemingly willing to do anything to save his own skin…and is very willing to kill again. It is a very bold move to have your audience spend the majority of the film following around a completely despicable character. After all, we’re never going to pity him, or show him our sympathies – there will be no catharsis for him – so in the interim until his inevitable fate, we will enjoy watching him squirm. His death, for us, will be a release – especially when young Marylee finds herself in peril once more.

There’s no reason at this point to reaffirm Charles Durning as one of the greats (RIP, sir), but I’ll reaffirm, gladly. At this time in his career, Durning was enjoying himself in little thrillers like this, as well as When A Stranger Calls and The Final Countdown, and he was certainly open to taking on the role of Otis, a complete scuzzball in every sense of the word. He’s an unapologetic murderer, this we know, and an insensitive asshole who doesn’t know when to quit as he takes it upon himself to begin harassing Bubba’s mourning mother, whom he assumes is behind the tragedies befalling his fellow vigilantes. But he’s also something else, too. Though the film does a very good job of straddling this fine line, it’s very carefully intimated that Otis is a pedophile. He’s a single male, one among many in the boardinghouse where he lives, and the earlier scene with Otis and Mrs. Ritter confirms as much, as she tells him she knows "exactly what [he is]. This is a small town. Everybody talks.”

This, frankly speaking, was a fucking ballsy move to impart on this otherwise straightforward ghost movie (made for television, no less). It also adds a very seedy new layer: Perhaps Otis hadn’t so impulsively killed Bubba simply because the man-child’s friendship with Marylee disgusted him. No… perhaps Otis was jealous, even being… territorial.

Gross.

Larry Drake’s screen time as Bubba is understandably limited, as he’s shot full of holes within the first twenty minutes, but it’s nice to see him play a simple and innocent character like Bubba Ritter. He is so ingrained in our minds thanks to his villainous turns in Dr. Giggles or the Darkman films that typically our only affiliation we have with the man is being a cigar-cutting or pun-hurling sociopath. To Drake's credit, it’s always tough and potentially career-damaging to play a character with developmental deficiencies, but Bubba really just comes across as a child – easily prone to fear and shy around girls. He’s charming and even cute – by design, as I’m sure the filmmakers wanted you to feel especially angry towards the men who eventually take his life.

The film is very dissimilar from the previously mentioned Night of the Scarecrow, Scarecrows, and Husk – those films' directors were not afraid to make their straw-headed killers vicious and violent. People are hacked apart, strangled, even raped with penetrating straw spears. But in Dark Night of the Scarecrow, all the gruesomeness is left to your imagination. The men are killed, oh yes, and in imaginatively painful ways, but never on screen. It is old school in its execution because it is old school. A swinging shaded bulb complementing a man’s desperate screams is far more affecting than a man being folded in half by random farm equipment front-and-center on screen.

Despite the obvious constraints of a television budget, director Frank De Felitta (The Entity) shows real skill and creativity. The first scene of the ghostly Ritter farm scarecrow stuck into Harliss' field is captured in one extreme long shot, making the scarecrow barely visible, yet still unnerving and nightmarish. But the second sighting in Philby's field is perhaps better; we see the man looking horrified at something off-screen and in the distance, and he begins to run towards it. Finally he falls to his knees as the camera pulls back...and reveals the scarecrow.

Stationary bird scarers have never been creepier.

De Felitta also knows how to use the quiet mid-western night to maximum effect. What should be peace and solitude is instead interrupted by the humming of machinery kicking on by itself, or the squealing of disturbed pigs, or the crunching sound of methodical footsteps. It's classy yet familiar, yet also entirely effectively.

Honestly, the film is smart enough to know all it needs to be scary is this:

Sadly, scarecrows are slowly being phased out of regular usage, as farmers are opting to instead use wooden silhouettes of large predatory creatures or even beach-ball-shaped contraptions that do god knows what, but do apparently scare away birds. More effective they might be, they are certainly less interesting.

The scarecrow has been used only moderately throughout horror cinema, which is a shame, because their visage is effortlessly creepy and could make for a good on-screen threat given the right approach. Unfortunately, most of the scarecrow’s voyage into celluloid have resulted in count-them-on-one-hand entries actually worth your time. 1990’s Night of the Scarecrow is a fun and low-budgeted little thriller featuring a very young and beardless John Hawkes; 1988's Scarecrows is a flat, though sometimes bizarre, offering; 2011’s Husk is a decent time-waster that gets more right than it does wrong. And the less said about the direct-to-video Scarecrow Slayer series, the better. But 1981’s Dark Night of the Scarecrow will likely always reign supreme. Recently resurrected for an unexpected video release in 2010, and nearing the end of its license before it goes back out of print, Dark Night of the Scarecrow, for decades, belonged to that dubious club of horror films that continued to live on after their first theatrical or television appearance through bootleg networks. Following a 1986 VHS release (and going out of print soon after), legitimate copies of the film were nigh impossible to track down. It was one of those movies that risked being lost with time. But, as any loyal horror fan will do when denied their white whale of a film, they set out to horror conventions or to the many websites specializing in unavailable or never released films to secure themselves a copy likely created from a 37th generation VHS tape.

When the legitimate release was announced in 2010, I wasted no time in snapping up myself a copy. After all, I had heard nothing but praise for the film for many years, and having a rough idea what it was about, I was incredibly interested and excited to give it a watch. About scarecrows, set on Halloween, and allegedly scary. Of course I was all over it. After all, the quote from Vincent Price proudly blazed across the front – “I was terrified!” – was quite possibly the only marketing a horror film would ever need.

My copy soon arrived and I saved it for near-Halloween. And I watched.

And though I found the film to be well made and well acted, I was surprised by how…uninvolved in the story I found myself. And I was a little disappointed in another regard: the lack of scarecrows. I was expecting to see that infamous canvas-bag face sitting atop the shuffling straw-filled figure as it chased down its victims one by one. But that didn’t happen. In fact, the lone scarecrow remains limp and still for pretty much the entire running time – and is only on screen for about five minutes.

I remember at the time chalking it up to just yet another film I had lost to the hype machine, as nothing could have lived up to the years and years of folks saying they recall having watched it when it aired on television and how scary it was, etc., etc.

But something unexpected happened: though I thought the film was reasonably good, I held onto it. (This is important to note, as I was once an avid collector of films, CDs, and books, and would immediately get rid of anything I felt wasn't worth keeping.) And in the days following my first viewing, I found myself thinking back on the film, as it had somehow stuck with me. So, a few weeks later, I watched it again.

And I got it.

I saw what the big deal was and this time I simply allowed myself to be taken away by the story.

In a nameless mid-western town, a young girl named Marylee Williams and a simple-minded man named Bubba Ritter (Larry Drake) play together in the middle of a field. These two are good friends – have been for some time – and this really bothers a few townspeople, namely Otis (Charles Durning), Skeeter (Robert F. Lyons), Philby, (Claude Earle Jones), and Harliss (Lane Smith). He and his cohorts believe that Bubba is potentially dangerous and perhaps even a pervert, and such should not be allowed near any young child. "He's a blight...like stink weed and cutworm that you spray and spray to get rid of, but always keeps coming back," Otis seethes. "Something's got to be done...but it has to be permanent."

While harmlessly sneaking into a backyard to play with a decorative garden fountain, a dog viciously attacks Marylee and Bubba manages to save her. She is brought to the hospital bloodied and unconscious and Otis naturally assumes the worst. He gathers up his hateful posse and heads out to the Ritter farm to exert some private justice.

Bubba’s mother (Jocelyn Brando), having hidden her son within the scarecrow poled in their back field, forbids the men from entering the house. She attempts to lie and says Bubba is nowhere on the property, but the men know better. They instead begin their search outside, and through the holes on the scarecrow’s burlap-sack face, Otis sees Bubba’s terrified eyes. The men open fire, killing Bubba with an obnoxious amount of bullets. Then they find out the truth – that Bubba hadn’t been the one who hurt Marylee at all, but had actually saved the girl’s life from what everyone learned was a dog attack. Otis places a pitchfork in the dead Bubba's hand, his mind already piecing together a possible way out of trouble. An eerie wind picks up immediately after...announcing a vengeance soon to come.

Otis and his posse are tried for Bubba's murder (rather quickly), but they claim self-defense, and because the prosecutor can present no witnesses and no evidence, the men find themselves free – at least from the courts. Having just gotten away with murder, the men are feeling pretty good. But then each of the men begin seeing the Ritter farm scarecrow – the same one in which Bubba had attempted to hide – planted in the middle of their own fields. And then the men are picked off one by one by an unseen killer in the order following their visitation by the scarecrow, as if someone were taunting them…or letting them know who would be next.

There are plenty of red herrings provided to us. The killer could be anyone: Bubba's mother, who in a fit of rage loses her mind and begins tracking down the men who killed her son; or perhaps it's District Attorney Sam Willock, who tried to prosecute the men and was nearly thrown back in shock when they were set free; it could even be one of the men responsible for Bubba's death, buckling under the simmering guilt he has successfully hidden away from his friends.

Or perhaps it's the ghost of Bubba himself, back from the grave to take his revenge on the men who took him away from his mother and his only friend...

A friend of mine was killed the other night.

So I heard.

They all think it was an accident. I don't.

There's other justice in this world.

Besides the law?

It's a fact. What you sow, so shall you reap.

Dark Night of the Scarecrow is intelligently engineered so that our antagonists suffer for pretty much the entire film. Though they begin to succumb to the fear of their being murdered, and are haunted by the harbinger of doom that is the Ritter farm scarecrow, they never show regret. They never break down and say, “Oh, I wish we hadn’t killed that poor man!” And because of this, we watch without conflict or guilt as each of the men are hunted down. We pity none of them are they are each killed on their own farms in the middle of the night. We certainly don't pity Otis, as the film bravely dedicates much of its time with this man who is seemingly willing to do anything to save his own skin…and is very willing to kill again. It is a very bold move to have your audience spend the majority of the film following around a completely despicable character. After all, we’re never going to pity him, or show him our sympathies – there will be no catharsis for him – so in the interim until his inevitable fate, we will enjoy watching him squirm. His death, for us, will be a release – especially when young Marylee finds herself in peril once more.

There’s no reason at this point to reaffirm Charles Durning as one of the greats (RIP, sir), but I’ll reaffirm, gladly. At this time in his career, Durning was enjoying himself in little thrillers like this, as well as When A Stranger Calls and The Final Countdown, and he was certainly open to taking on the role of Otis, a complete scuzzball in every sense of the word. He’s an unapologetic murderer, this we know, and an insensitive asshole who doesn’t know when to quit as he takes it upon himself to begin harassing Bubba’s mourning mother, whom he assumes is behind the tragedies befalling his fellow vigilantes. But he’s also something else, too. Though the film does a very good job of straddling this fine line, it’s very carefully intimated that Otis is a pedophile. He’s a single male, one among many in the boardinghouse where he lives, and the earlier scene with Otis and Mrs. Ritter confirms as much, as she tells him she knows "exactly what [he is]. This is a small town. Everybody talks.”

This, frankly speaking, was a fucking ballsy move to impart on this otherwise straightforward ghost movie (made for television, no less). It also adds a very seedy new layer: Perhaps Otis hadn’t so impulsively killed Bubba simply because the man-child’s friendship with Marylee disgusted him. No… perhaps Otis was jealous, even being… territorial.

Gross.

Larry Drake’s screen time as Bubba is understandably limited, as he’s shot full of holes within the first twenty minutes, but it’s nice to see him play a simple and innocent character like Bubba Ritter. He is so ingrained in our minds thanks to his villainous turns in Dr. Giggles or the Darkman films that typically our only affiliation we have with the man is being a cigar-cutting or pun-hurling sociopath. To Drake's credit, it’s always tough and potentially career-damaging to play a character with developmental deficiencies, but Bubba really just comes across as a child – easily prone to fear and shy around girls. He’s charming and even cute – by design, as I’m sure the filmmakers wanted you to feel especially angry towards the men who eventually take his life.

The film is very dissimilar from the previously mentioned Night of the Scarecrow, Scarecrows, and Husk – those films' directors were not afraid to make their straw-headed killers vicious and violent. People are hacked apart, strangled, even raped with penetrating straw spears. But in Dark Night of the Scarecrow, all the gruesomeness is left to your imagination. The men are killed, oh yes, and in imaginatively painful ways, but never on screen. It is old school in its execution because it is old school. A swinging shaded bulb complementing a man’s desperate screams is far more affecting than a man being folded in half by random farm equipment front-and-center on screen.

Despite the obvious constraints of a television budget, director Frank De Felitta (The Entity) shows real skill and creativity. The first scene of the ghostly Ritter farm scarecrow stuck into Harliss' field is captured in one extreme long shot, making the scarecrow barely visible, yet still unnerving and nightmarish. But the second sighting in Philby's field is perhaps better; we see the man looking horrified at something off-screen and in the distance, and he begins to run towards it. Finally he falls to his knees as the camera pulls back...and reveals the scarecrow.

Stationary bird scarers have never been creepier.

De Felitta also knows how to use the quiet mid-western night to maximum effect. What should be peace and solitude is instead interrupted by the humming of machinery kicking on by itself, or the squealing of disturbed pigs, or the crunching sound of methodical footsteps. It's classy yet familiar, yet also entirely effectively.

Honestly, the film is smart enough to know all it needs to be scary is this:

Oct 15, 2013

Oct 14, 2013

#HALLOWEEN: TRICK OR TREAT

Don’t bother trying to find it. You won’t find anything about the name of the town or what happened here. This manuscript will be found long after the events that transpired in this place, but I hope against everything else that you’re someone in a position of power. I pray to God Himself that you can prevent this from ever happening again, but I don’t want to give you too much credit. Like me, you are only human, after all. They are not. They’ve been around for a very, very long time.

Fat chance, really. You probably don’t want that responsibility, and even if you did take it upon your shoulders to track them down, you can’t single-handedly stop the children. Their manipulators are not “on the grid.” Whoever engineered this is in control of the world on a very disturbing level.

This is what I want you to do. Read this, if they’re still legible, and take what you will from them. Don’t go on a wild goose chase, and realize that when you find this book that it will not be in the place where I left it. They’ll move it somewhere else, to deceive you. I’ve left my mark on a tree there. Only then, when you see my name, will you know, “this is the place.” You may have even heard of it in the history books, but be assured, any rumors on Wikipedia or Google pages that you pull up will be guess-work at best. None of them are even close to the truth. When you find the place, there may already be another town just like it. That’s what I’m trying to stop. If we’re not successful, then just realize, above all things, that evil exists. I’m not talking about bad people, or tragic accidents. I’m talking about real, intelligent, ancient evil. It is calculated, and it is always one step ahead of you. Should you decide to take my place and become the paragon to prevent the corruption of the hearts and minds of children, I thank you in advance.

I told you that I’m human. I lied. I used to be, before All Hallow’s Eve on that fateful night. I’ve been alive since then, far longer than any human being, and the reason is because I love children. I’ve always loved them in their purity and their innocence. That’s why I was taken in by their ruse. That’s why I’ve finally decided to put all this down, centuries later. I won’t be here much longer, and someone has to take up the burden.

I’ve waited… until I saw them return. They’ll be back this year. They’re planning the same thing again, and I can’t stop them. Again, I can’t expect that much from you, but I’m only giving you all this so you’ll believe me. I have to be believable. If you think I’m crazy, you’ll ignore this, and more people will disappear. It’s time to tell you what happened. I’m rambling.

Back then, All Hallow’s Eve was the time for evil’s ascension. You’ve all forgotten. If you left your house on that night in the old country, you were a devil worshipper. “Halloween” was not the term we used. We fled to the shores of this country because we were persecuted for our lifestyle choices. We worshipped nature, the changing of the seasons, the solstice of spring, autumn, winter, and summer. In the purest sense of the word, we were Druids. Our names and accents were English, but we were servants of the earth.

We were some of the first to celebrate it as a holiday. The natives here were puzzled by our behavior, but also frightened by it, and so they left us alone. They misunderstood. We were not the ones to be afraid of. At the time, I was relieved. They’d attacked us in our settlements, time and time again, but as it drew closer to the end of October, they stayed away. Maybe in their own noble bonds with the earth and soil, they knew something terrible was on the horizon.

They were right. John Hunter’s little boy wanted to be a native, with a bow and arrow and a real headdress. Little Mary Taylor made a dress that was crafted after the local schoolhouse teacher’s prettiest outfit. She idolized her educator, of course. They all had their get-ups; they were the first trick-or-treaters in what was to become the United States of America, one hundred and fifty years later. We sent them out to frollick about the settlement, collecting apples and tarts and other sweet things in to their burlap goody bags. There were no Snickers or Milky Ways, and yet, the magic of this “holiday” held no less sway over them than it does the youth of our current time. They dress up as the Joker, the Power Rangers, the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. These children were their predecessors.

I sent my daughter with Mary and John Hunter, Jr. Despite our mistrust and wariness of the Anglican church and the monarchs that presided over it, my little girl was dressed as the Queen of England. I refused to crush her fantasy world, and so I simply indulged her. We heard promises to return after sundown, to say yes ma’am and no sir, and not to linger too long if they were invited inside the households of our community.

We didn’t realize that the house on the edge of the settlement existed until we saw the children go inside. There were no lanterns or sources of light in the windows, no fire or harvest dolls on the outside of the dwelling. As we sat in the middle of the town hall, imbibing in the pleasures of distilled moonshine amongst our brethren, we watched our young ones gravitate across the middle of our town, to the foreboding household that had seemingly been constructed overnight. When we gazed upon it, it seemed as though the place were “shimmering.” It pained my vision to look upon the building, as if my senses were being forced and propelled in another direction. Such a thing is difficult to put in to words, but I seemed to be the only one who realized that our kids were all heading to the same place. When I questioned John Hunter as if something were odd about their actions, he stared at me as if I were insane.

“What do you mean?” he asked. “There’s no house there. They’re going to play by the stockades.”

The sun had set by that point, but as I said before, none of them were concerned. The natives hadn’t shown up for weeks. I decided to walk to the phantom dwelling that only I and the children could see, to peer inside and see who these new settlers were, and why it called to the youths as if it were a black hole in a sea of stars.

I tried to stand outside, to look through the window, but when I saw what was happening, it was too late. I breached the doorway with my buck-knife drawn, but there was nothing about the things inside that I could harm with a weapon.

There’s something deep inside of us, something embedded within the human spirit, that’s perfectly aware when we encounter something truly terrible. Fear, horror, evil, revulsion…. it all hits you in a spastic wave, like a fierce exploding bullet that shatters the innermost parts of your soul with a relentless and powerful fury. I saw it in that moment, standing in that darkened doorway.

They weren’t people.

They were halfway there, lingering over the unconscious bodies of my daughter and her peers in their hooded black robes of half-existence. There was one, in particular, who made me feel as though my eyes would pop like ripened cherries when I stared at it. It was the leader, the source of that tug, that pull... and it was slowly fading, disappearing like a gaseous black cloud of death, through my little girl’s nostrils and mouth. She was gasping for air, as if every breath after the one that preceded it were filled with acid... as if she were hungry for real, fresh air in her small lungs. With every breath, the figure faded deeper in to her, along with the rest of them.

I wish I could say that I was a hero, and that I hacked them all to bits; I wish I could say that I saved the day and made Halloween a night when the worst thing that children have to worry about is poisoned candy. It didn’t happen. There was one of them left, floating toward me on elongated, blackened tendrils of shimmering nothingness. By all real means of my imagination, it shouldn’t have BEEN there, but it was, and soon, it was going inside of me. The last thing I saw were their little feet, scurrying out of the phantom-house and in to the town. I FELT that something terrible was about to happen. I had no idea. Everything went black, and then, I was outside of myself. I was conscious, but observing my feet, my hands, doing things beyond my own scope of physical control.

They led me and our children in to our meeting hall, where, of course, the kids were embraced by the open, loving arms of their parents. I witnessed the betrayal, the brutal moments in which the truth instilled by the love for family and offspring would transform in to a cause for the destruction of our village.

They absorbed them. There’s no better adjective for what happened. One moment, they were there, and seconds later, they were nothing but dark essence, filtering in through the eyes and noses and mouths of their devil-children. It was over in minutes. A night that should have been a celebration of nature, of the seasons, had turned in to the end of everything that we knew and loved here in our new land.

I started to fight it. The kids knew. The moment I began to resist, to try and reclaim my limbs and mind from the corrupting influence within, their heads snapped back from their feast of souls to survey me in my struggle. My daughter’s eyes were sunken, black pools of the abyss, devoid of any emotion, any semblance of the bright-eyed stare that she once held for me in all her love and adoration for father. I miss that the most, really. The way she’d run to me when I came in from the fields every evening as the sun went down. I lived for that. What reason do I have to live now, other than to find her and stop them? I’m incapable. That falls on you, my friend.

They took the part of my daughter that counts, the part that I loved and cherished, and turned her into a servant. You ask me why I’m still alive, and again, it’s because I love her, so very, very much. Her body is a hollow shell, filled with the malice and blackness of evils beyond our world.

The black-robed things have grown as centuries have passed. They are from some place that is not of this universe, but their urgency, their hunger, to devour and destroy, is insatiable. It’s an exponential, amplifying contagion on mankind, and All Hallow’s Eve is their pinnacle, their Christmas. I’ve done my best to warn you throughout history, to leave my mark in places where their desolation has left nothing but dust on the wind and empty houses. A deserted football field in a Texas ghost town. A card room in the back of a night club in Chicago, right under the nose of civilization. Roanoke Island, North Carolina, before John Rolfe found it in the aftermath.

The thing that I expelled through sheer force of will alone has left me with an unusually long and empty life, devoid of anything but my desire for revenge. I have failed. I’m pleading with you. October 31st is not long away. My little girl, or what’s left of her, is going to lead them to the same place. It’s been re-founded, except now, it hums with sport utility vehicles and cell phones. I don’t want this to happen to your child.

Go to Roanoke, and stop them from repeating the ritual. Those bodies they inhabit now are frail, on their way out. It’s been almost five hundred years. They’ll need new ones on this Halloween. Look for a building that appears as though it shouldn’t be there. It will be across from that very tree where I signed my name, where I made my mark. I changed my title, named myself after the tribe of natives who knew it was coming…. who, perhaps, tried to warn us, but for some reason, we failed to heed or recognize their warnings. They were more closely attuned to the earth than us, and yet, they were still wiped out, eventually.

Trick or treat?

Go now. You don’t have much time.

- Croatoan

Story source.

Oct 13, 2013

REVIEW: JUG FACE

Jug Face is a tough film to breakdown and criticize. It is extremely well-made with what no one would refuse as an original story. It is an uncomfortable experience at times, and injected with the kinds of seediness you'd expect in a film featuring incest, filthy backwoods simpletons, roadkill for dinner, and Larry Fessenden.

In Jug Face, a young girl named Ada (Lauren Ashley Carter) looks her destiny literally right in the eyes and refuses it. This decision sets off a chain of events that will rattle her small backwoods community and leave behind a wake of blood. As simple a summation as I can make without sending readers less willing to sit through an uncompromising experience like Jug Face running for the hills. To offer up additional story details (as I'll do in a moment) is to risk turning off those looking for a more straightforward story about forest voodoo, but, you should know exactly what you're getting into.

Writer/director Chad Crawford Kinkle has crafted an interesting story here. It's layered enough to bring legitimacy to even the most absurd development, but purposely vague enough that the events of the present aren't overshadowed by the mythology of the past. And from a stylistic standpoint alone, Jug Face is very good. Its unique story is backed up by a great cast, including Larry Fessenden and Sean Young as Ada's parents, and Sean Bridgers ("Justified") as the simple-minded shaman of sorts.

Deep southern territory is always an interesting place in which to set a story. It is in these areas where ties to religion remain the strongest and the most unshaken. At first its people were only characterized by their religion, but recently, under the political microscope, their religion has come to define them. And it's made them an easy target for mockery. Their beliefs mixed with their unfortunate histories of offensive ideologies (and add a dash of that long southern drawl) can sometimes make them seem simple, foreign, and even intimidating. So, when you've got a film in which a small group of inbreeding families live deep, deep in the southern woods and who offer human sacrifices to a magical pit in exchange for said pit's healing powers, and when the person being sacrificed is chosen by a ceramic jug made by a simple-minded man with ties to a mysterious force, well, you might just respond with, "Yeah, and? This is the south, after all. Who knows what goes on there?"

None of that is really supposed to read as offensive; instead it's supposed to shine a light on the extreme chasm between the northern and southern sensibilities that have been in place since basically the formation of the United States. The north thinks the south are simple and crazy; the south thinks the north are godlesss baby killers. This is not something with which I necessarily agree, but a person can only resist such broad beliefs and stereotypes before some of them begin to take root. (I bet I'm one of the few with the balls willing to admit that.)

The events of Jug Face are far-fetched, ridiculous, and some might argue stupid. What's not far-fetched, ridiculous, or stupid, is that I could very easily read in tomorrow's paper that a small patch of isolated people living in the woods passionately believed in the power of a magical pit, human sacrifice, and anthropomorphic jugs. I'm not making fun. I'm saying this because this is where Jug Face is at its most affecting and powerful. When it comes to religion, people will believe anything. They will believe in the resurrected dead, angels, demons, magic, miracles, reincarnation, and anything else, so long as their parents before them believed it and bestowed it at a young enough age.

Jug Face is creepy, seedy, disturbing, startling, and a little fucked up.

And I highly recommend it.

#HALLOWEEN: MOUNDSHROUD

“Miraculously, smoke curled out of his own mouth, his nose, his ears, his eyes, as if his soul had been extinguished within his lungs at the very moment the sweet pumpkin gave up its incensed ghost.”

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)