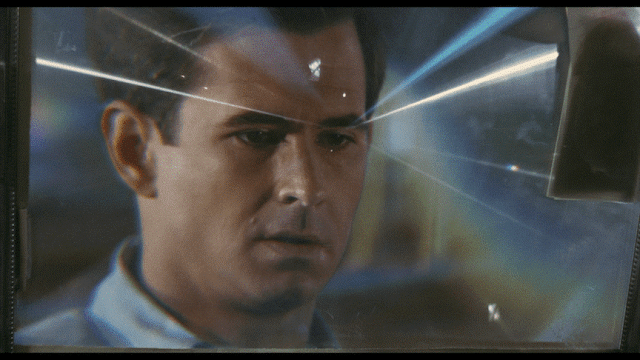

Budding cineastes slowly developing their love for cinema in the Internet Age have likely become aware of Zardoz's existence through the infamous image of Sean Connery dressed as a viking by way of a Prince music video while grasping a rather modern looking pistol and smiling right into the camera. It's an image that invokes thoughts of, "Oh man, I need to see this...but, maybe later."

Before it went out of print, home video distributor Twilight Time resurrected this strange title for another lease on life. The definition of a cult film, Twilight Time ran through its typical allocation of 3,000 units quicker than many of its other titles, and after having seen Zardoz for myself, I can understand why: it's so goddamned weird that it's clearly the kind of title that only appeals to a very few, and those to whom it does appeal, it appears pretty hard.

Frankly, I'm at a loss as to how I might adequately provide even the loosest iteration of Zardoz's plot, so I'm not going to try. Twilight Time's own synopsis:

Writer-director John Boorman’s fabulously bizarre Zardoz (1974) is a visually stunning science fiction/fantasy fable starring Sean Connery as the spanner in the works of a dreamily languid future society. A primitive Adam, Connery’s Zed charges like a bull through the china shop of a civilization from which all signs of lusty humanity have been drained.

Added to that: by film's end, Connery will end up in a wedding dress before he turns into a skeleton, all while holding hands with...another skeleton.

Zardoz is an entirely maddening, confusing, frustrating, highly amusing experience that cannot be easily summarized into mere words. To try would be to harvest from the film its identity, its uniqueness, and its complete lunacy. Zardoz is artistic expression unrestrained, anchored by the presence of former James Bond Sean Connery, whose involvement wrongly assures the most mainstream of audiences that he's made a film that appeals to everyone who enjoys going down to the cinemas on a Sunday afternoon looking for a brief slice of harmless escapism. Zardoz's "story" is baffling. Zardoz's "message" is baffling. That Zardoz was produced and distributed by a major motion picture studio is utterly baffling. But it's here: now, and for all time. It's recently turned forty-five years old, and its legend remains firmly intact. It's wonderfully and weirdly captivating, and deserves to be seen once. Though it may demand more than one viewing to fully appreciate how utterly mad it is, the jury will be forever out on who would ever do such a thing.

A good friend of mine put it best: "Sean Connery turned down both The Matrix and The Lord of the Rings because he 'didn't get' them, but he said yes to Zardoz."

You figure that one out.

Zardoz is less of a film and more of an experience. Like that fever dream you once had following your all-night puke-a-thon the last time you got that really nasty stomach bug from the half-KFC/half-Taco Bell, Zardoz probably makes sense somewhere in the outer-reaches of artistic creation, but here on Earth, it's frankly one of the most absurd and deeply abstract 105 minutes of your lifetime. What on the surface may look like a silly B-movie accidentally starring Sean Connery is actually an art-house experiment straddling the line between erotic thriller and science-fiction extravaganza purposely starring Sean Connery. Those interested by such a breakdown may possibly use Jonathan Glazer's 2013 film Under the Skin, another unorthodox film about cross-universe alien races driven by a deconstruction of sexuality, as a guide to determine what kind of experience Zardoz may provide. One thing is for sure: you've never seen anything like it.

Zardoz has spoken.