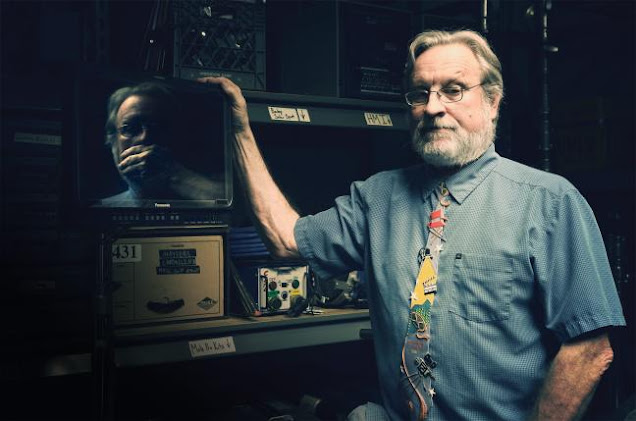

Writer/director David Schmoeller might not be a household name—maybe not even for your most prolific of horror fans—but he’s given us two undeniable minor horror classics: 1979’s

Tourist Trap and 1989’s

Puppet Master (which would go on to spawn nine(!) sequels). Except for his steady creation of short films, he has been rather quiet. After thirteen years, Schmoeller has returned with a very different kind of horror story...one sadly based on a true story.

David was gracious enough to participate in an interview—we also spoke about

Tourist Trap in a separate interview—in which he dishes on his newest independent feature, life imitating art, Fox News, and much more.

TEOS: Little Monsters (review here) is based on a true story – more specifically the 1993 James Bulger murder of England. What was it about this event that drew you to turning it into a film? Given the event happened twenty years ago, was this idea slowly simmering in your mind over time, or did you only somewhat recently read about it?

SCHMOELLER: I clearly remember seeing the news of the Bulger murder in L.A. when it happened. The news media had B/W video images of the kidnapping by the two ten-year-old suspects from the many shopping mall cameras. It was a big, international news story. And the nature of the killing was very disturbing. While I followed the story, it did not immediately become an idea for a movie. A few years later, while I was a William Randolph Hearst fellow at the University of Texas at Austin, I started doing research on the story. I think when the murderers were released from prison when they turned 18, the story made the news again. I think this was when I started to become more interested in the story as a possible film idea.

TEOS: The lives of the real murderers seem to closely parallel those of your film versions during the murder, the trial, and their subsequent release. At what point did you let your artistic creativity take over and present a "what-if" scenario?

SCHMOELLER: Little Monsters

SCHMOELLER: Little Monsters is completely fictional, although inspired by the actual event. What made it an interesting story for me was that when the two boys, teenagers when released…they passed laws in England that made it illegal for anyone to reveal the new identities or locations of the child killers. They could be living right next door and no one would know. This was another reason the story was so compelling – both in real life and in my growing story line. What happened to the boys after they were released, how did they feel about their crime, would they be able to cope with what they had done (did they even feel bad about what they had done?), and would they be able to live out their lives with new identities? All these issues where completely unknown, so, I had to fictionalize those things. In 2002, I took a group of UNLV film students to the Fringe Festival in Scotland, and since I was going to be there a month, I decided to write the screenplay, which then was called

Don’t Look Back. I did a few rewrites, which took me the next year or so, then I tried to have my agent set it up as a film for me to direct, but it was considered too dark for Hollywood. In 2008, I produced (and personally financed) a feature film called

Thor At The Bus Stop, which was written and directed by Mike and Jerry Thompson. It’s a very good quirky comedy available at Amazon, iTunes, Vudu, etc. When I realized I actually had the means to make a feature film, I decided to make

Little Monsters – and direct it. While I had written and directed a dozen or so short films since I left Hollywood, I had not directed a feature film in 13 years. So, it was exciting.

TEOS: What was it about the Hollywood system that you felt you needed or wanted to leave it behind?

SCHMOELLER: I have no problem with the Hollywood system. I liked working in Hollywood (mostly – every once in a while you get stuck with an asshole, but that happens in all walks of life). My decision to leave Hollywood for academia was strictly a financial decision. I am better paid, have more job security, and am more respected in academia than I was working in Hollywood.

TEOS: Speaking as vaguely as possible to avoid spoiling a turning point in the film, there's one particular scene where one of the murderers has a heated confrontation with his mother, who shows nothing but disdain for him. She's presented as a rather hard woman leading up to this and the film suggests she is a potential explanation for her son's dangerous behavior. Do you believe that the behavior of a child directly reflects his or her upbringing? Or do you believe we as individuals all have the strength to overcome such an upbringing and still become meaningful contributors to society?

SCHMOELLER: At one point in the screen-writing process, I had a character say: “It’s always the mother's fault.” I believe parents can and do play a major role in how their kids turn out. But there is no common rule. You can have awful parents and turn out OK, or you can have great parents and not turn out so good. My own mother was an extraordinary beauty as a child and a stunning beauty as an adult. Because her beauty was how she was defined, she was a spoiled child and a spoiled adult. She really didn’t mature as she grew into adulthood, even though she was very smart – as smart as she was beautiful. I think her beauty was a huge burden to her as an adult. So, even though she tried, she was really not a good parent. This was before the women’s movement of the '60s, so, my stepfather expected her to be a stay-at-home housewife. Eventually she became a Valium-wife and spent much of my childhood in bed. And when she wasn’t sleeping, she was bored, and sometimes angry. Not anything like the mother in

Little Monsters, but still, not a very good mother. We called her “our crummy mother.” I think my older brother suffered much more damage than I did because he was always angry at our crummy mother and our absent stepfather, so he acted out. It was all way too much drama for me as a child, so I just kept to myself. When my older brother went off to college, I knew I would not survive my mother alone, so I left home at 15. And I quickly learned how to be very independent, which helped me greatly in life – especially when I went to Hollywood in the 1970s.

TEOS: In doing my own research into the James Bulger case, I found that, of all things, Child's Play 3 was cited as a negative influence in the lives of the two killers, as those involved in the case proved that the kids had not only watched the film in the months leading up to the murder, but also supposedly detected an instance in which they "imitated" a specific scene. Being that you, as a filmmaker, have dabbled in the "killer doll" sub-genre, and worked largely in the horror genre in general, do you ever feel any responsibility as filmmaker for the content you put out there for public? Do you feel it has the power to influence?

SCHMOELLER:

SCHMOELLER: This is a frequent charge, especially when there is a particularly horrendous killing by younger killers – kids or teenagers: “They must have been influenced by a horror film.” People want a way to explain a horrible event, and sometimes the answer is to blame it on a film, and sometimes it’s to blame a parent. I understand this. It is difficult to explain senseless killing. I DO think movies can have a very powerful effect on viewers, especially children. And I do not think children should be allowed to watch inappropriate films. One of the better examples comes from my own work.

Tourist Trap was given an inappropriate rating – it was given a PG instead of an R. We were shocked when we received this rating from the Ratings Board. I had not let my own son see the movie – he was 8 or 9 – because I thought it was just too intense and too disturbing. And that tame rating hurt our theatrical release. Who wants to see a tame horror film? Because of that rating, however, it could play on afternoon television. And it’s the reason most responsible for

Tourist Trap having a second life, and to have grown into cult status. All those traumatized children who saw it on afternoon TV. I can’t tell you how many people have said to me: “I saw

Tourist Trap on TV when I was seven and it scared me to death.” What safer thing for a parent to say to a young child on a Saturday afternoon? “Billy, Mom and Dad are busy – why don’t you go watch TV with your sister…?” [

sarcastic smile]

In terms of the responsibility of the filmmaker? Movies are an art form. The responsibility of the filmmaker is to make a good, compelling film. There are very few restrictions (there are certain legal restrictions: you can’t shoot a snuff film; you can’t shoot child pornography, etc.). Wes Craven has spoken fairly articulately about “violence in cinema.” The filmmakers of the ‘70s were informed in part by the war in Vietnam that we watched on the nightly news. Craven maintains that nothing he has ever put on film is as violent as the images we saw on TV every night during that war.

TEOS: The two young actors who played James Landers and Carl Withers were especially good and playing very challenging roles. Where did you find them? What was the casting process like?

SCHMOELLER: Both Ryan LaBeouf and Charles Cantrell were/are students of mine. I had directed Charles in a short film called

Ha, Ha, Horror, so I had [previously] worked with him. Ryan is an all-around talent – writer/director and actor – only I had only seen him in comedies. But, he has a nice quality and an intelligence as a person; I just thought he had this special talent that would show up on the screen. They both work completely differently as actors. Charles likes to talk about the scene or his character, has lots of questions, and approaches his work with a “method” process. Ryan just shows up in character and uses his intelligence to play the part. It was such a joy to work with both of them. I also think their performances were greatly helped by Ben Zuk, my editor.

TEOS: Both the editing and the intimate nature of the narrative lent a specific realism to the film, including your use of sit-down interviews. The realistic approach I think is the film's biggest selling point. As you were writing, did you ever have to scale it back? Did you ever veer too far into over-the-top territory, perhaps without realizing it?

SCHMOELLER: The early versions of the story had many more of the sit-down interviews – so much so that they dominated the story. The central narrative in

Little Monsters, the story of the two boys, was eclipsed by the detailed facts of the story. I think what you are asking me about is the (realistic) tone of the film. We worked hard on the tone, but there may be some side segments that don’t work for some viewers as well as others (like the TV Tabloid personality). I don’t think G. Gordon is over-the-top, even though I think he is clearly ridiculous (just like I think Glenn Beck is ridiculous), and we did worry he might be mess with our tone. At the same time, I know from my horror film experience that you need to allow the audience to breathe, even laugh out loud from time to time.

As I tell my students, when you make a film, it’s just as likely that you will fail as it is you will succeed.

TEOS: What was the production process like? How long was the shoot?

SCHMOELLER: May May Luong, my producing partner and I, both have day jobs. I am a university professor and May May works in production, so we shot

Little Monsters mostly on the weekends over a 3-4 month period. Everyone who worked on the film were either students, who had classes during the week, or they had day jobs. It’s not the best way to shoot a film, but it does work. We shot the film over 24 days, although not all days were full days.

TEOS: Your portrayal of the media isn't exactly flattering, but the conservative talk show host, who actually laughs along with a caller threatening to discover the boys' secret identities and commit violence upon them, is especially obnoxious. How seriously do you personally take the role of media in our society, and do you think it has the potential to be harmful?

SCHMOELLER: I think certain segments of the media, like certain segments of our political system, are really shameful. And when you have some of the more scandalous crimes, such as the recent Jody Arias trial, the Menendez Brothers murder, the JonBenét Ramsey murder, or OJ – pick your famous killing – the media doesn’t always look so good. Is it the public that craves these stories, or the media who benefits from the high ratings? It’s both. I think some of the characters on Fox News (cable) are especially destructive to our society. I think they are flame-throwers for the big salaries they can make by yelling “fire.” And it seems the more outrageous, the more money they make. Glenn Beck, Bill O’Reilly, Rupert Murdoch, Rush Limbaugh – these are media personalities and entrepreneurs, not newsmen. It is called “hate radio” because they are hateful people and they teach listeners to be angry and that it is OK to be hateful and outraged. I have students – not many, but more than I would like to have – who feel entitled to express their anger and outrage, and they do so at inappropriate times and places. They have been damaged by these media personalities, not educated.

TEOS: Your use of sit-down interviews does an effective job of making the story feel as real as possible. Did you write these interviews from scratch, or were they based on actual interviews given at the time of the James Bulger murder?

SCHMOELLER: I did a lot of research for

Little Monsters over the years. Certainly, the breadth of players – the large number of people coming from all walks of life – came out of that research. The Clarence Gilyard speech (the criminologist at trial) where he talks about how many people are affected by a single act of violence…not the words themselves, but the essence of that comment, came out of that research.

TEOS: Audience reaction (or maybe I should clarify non-audience reaction) has condemned the film; they've said things like "How dare they turn this story into a film!" and "What would the families think?" Considering we had a film about 9/11 made five years following the actual event, or a film about killing Osama Bin Laden only one year following, what is it about this particular story that have made people cry foul? Is it because the violence is regulated to children this time, as opposed to adults like it normally is?

SCHMOELLER: I think you are talking about internet comments to postings about

Little Monsters; audience reactions at the screenings [I’ve attended] have been overwhelmingly positive. I think a person who lives in England and lived through the media experience of the Bulger murder, may have a different reaction to the film than someone who doesn’t have that firsthand experience.

And the issue of children killing children can be particularly disturbing to a lot of people. A lot of dog-lovers hated

Amores Perros because of the brutal dog fighting scenes, despite the fact that it was an excellent movie.

My mother, who was informed by the zeitgeist of World War II, thought

Saving Private Ryan was an awful movie. What she was really reacting to was the opening Normandy beach-landing scene, which was so graphic and so realistic. To her, World War II (actually, I am referring to immediately after the war) was really a romantic event; she was young and beautiful when she met and married my stepfather, who was a returning WWII bomber pilot and looked handsome in his uniform. He never talked to her about the war – AT ALL, ever – and so seeing

Saving Private Ryan all those years later shattered her romantic notion of what was probably the best time of her life.

Movies are not for everyone. In fact, they are probably for only a very small audience, especially these days when there are so many other things fighting for people’s attention. I am making something for a very small segment of the world. And I am sure there will be some vocal haters. As Carl Gunther in

Crawlspace would say: “So be it.” All I can do is make the best movie I can and hope at least a few people appreciate it.

TEOS: If you could say anything to the real murderers of James Bulger, what would you tell them?

SCHMOELLER: “Did I get any of it right in my movie?”