Boss, also known as The Black Bounty Hunter and its original/credits title Boss Nigger (the one and only time I’ll use that particular title, and for search/posterity only), was released less than one year after Mel Brooks’ Blazing Saddles. Both films saw a pretty similar plot, though the latter was played for much broader comedic effect: a black sheriff presides over a white town in the Old West and shakes up their culture — along with their women. And while Boss is a comedy, it’s not nearly as on the nose as its most immediate colleague. Being a Blaxploitation title, it also strives to upset the status quo by deviating away from the comedy to revel in darker aspects of humanity’s ugliness. Much of this comes from the hugely offensive exchanges that Boss (Fred Williamson) and his deputy, Amos (D’Urville Martin) engage in as they first arrive in town. (The n-word is thrown around more liberally than Tarantino’s Django Unchained, and that’s saying something.) But it also comes from the violence, the tragedies faced, and in the generally despicable way that the white town treats black and Mexican characters. The Blaxploitation sub-genre could do this like no other, and though it’s a cinematic movement not taken all that seriously due to some of the dubious titles that were released and the unintentionally amusing tropes that became legacy, always hidden within some heinous concepts was an important, and sometimes smartly rendered, morality tale. (Williamson’s Black Caesar is the best example of this.)

Williamson, who wrote and produced Boss, sometimes falls victim to too broadly showing whites as offensive — even those who aren’t trying to be. “Our family in Boston had black people working for us,” begins the white Miss Pruit (Barbara Leigh), and already you begin to cringe — openers like this equate to “I’m no racist, but..” in real life. “They were good people. They used to sing and dance a lot. I used to love to watch them.”

Cut to this face:

In fact, there’s exactly one white character — Pete the Blacksmith — who is a decent man right off the bat; he doesn’t start off as horrid and bigoted before learning the error of his ways. Williamson’s script suggests that, in a town of, maybe, a hundred citizens, one of them isn’t racist.

Yikes.

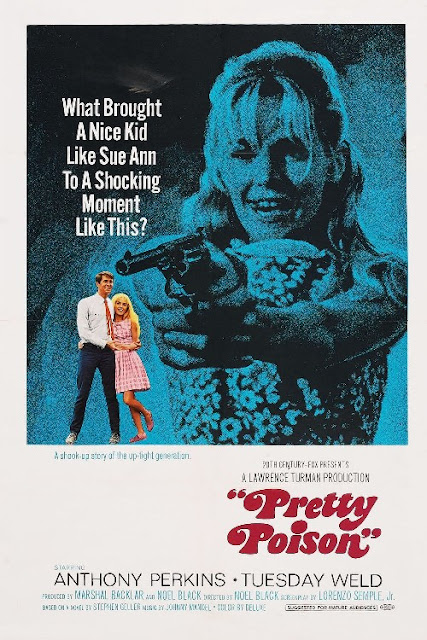

Though not taken very seriously (Blaxploitation might rank even below horror, which I never thought was possible), the sub-genre was instrumental in doing one main thing: exposing white audiences to black culture, in an effort to humanize them, by sneaking it into otherwise mainstream concepts for films. It’s no mistake that Blaxploitation was launched and enjoyed a nice long successful run following the turbulent fight for civil rights during the 1960s. It was a direct response and reaction to uncertain times and deeply rattled communities. Super Fly is one of the best examples of this covert exposure to black culture, during which the film stops the action several times as its main cast of characters visits a club to watch entire song performances by the film’s soundtrack contributor, Curtis Mayfield. Boss doesn’t follow this same approach, forgoing a look at black culture and instead focuses on the black experience; even when its black characters are in positions of power, specifically law enforcement, they still suffer the indignities of being treated like human garbage by the townsfolk. It’s just that they’re now in a place where they can do something about it. You’ll note, amusingly, that when Boss and Amos begin posting new ordinances all around town about what’s now considered illegal, and what kinds of fines those infractions incur, none of them rank more than a $5 fine — unless, of course, someone uses a racial epithet against someone else. That ranks a solid $20 fine or a day in jail.

Much of Boss is very funny, but it’s that kind of humor where you feel conflicted for laughing, even though that’s what was intended. Williamson knows there’s humor to be found in casual offense; I can’t even imagine what the pearl-clutchers of today’s easily-outraged populace would think as they watched. The strongest point of Boss’ use of humor is that the viewer becomes more easily disarmed during the moments that are genuinely dramatic. You spend so much time laughing about how Amos likes to pursue “fat women,” or at how obliviously terrible the town can be to Boss and Amos, that once a young boy is trampled in the street by the film’s villain, it’s not something you’d expect and it packs a surprising punch.

Blaxploitation very rarely infiltrated the western genre, even though the idea to do so harks back to 1938 with Two-Gun Man from Harlem, but with Williamson as the lead/co-writer/producer and veteran Jack Arnold (Creature from the Black Lagoon — irony!) at the helm, it’s doubtful any other duo could have pulled off a more entertaining and even poignant film.