Happy Return of the Living Dead Day!

My love for the horror genre was written in the stars long before I ever fired out of my mother. But certain films along the way cropped up early on during my wee-one years just to make sure I stayed on the right path: Don Coscarelli's Phantasm 2 was there to show me that not every battle between good and evil had a happy ending. Wes Craven's A Nightmare on Elm Street proved that no place–not even your bedroom–was safe. And Dan O'Bannon's The Return of the Living Dead proved that "horror" could be hilarious.

Rumors suggest that following the bungled release of 1968's Night of the Living Dead, in which the filmmakers lost copyright to the entire film following a last-minute title change, George A. Romero and his partners John A. Russo and Russell Streiner parted ways, each divvying up this potential new zombie franchise to take in different directions. Romero was awarded the partial phrase "of the Dead" for all future "official" sequels while Russo and Streiner walked away with "of the Living Dead" for less official spinoffs. Now, is this true? As Trump says, all I know is what I read on the internet. But it sounds so silly and spiteful that I wouldn't be surprised if it were. Having said that, Romero obviously went on to create two celebrated sequels, Dawn of the Dead and Day of the Dead, along with...some others...while Russo, Streiner, and Night alum Rudy Ricci would wait to seize on their creative cinematic rights until 1985, which saw the release of The Return of the Living Dead.

Despite all the contributors (ultimately the Night veterans had very little influence on the final product), The Return of the Living Dead is fully a Dan O'Bannon film. Twenty years before Shaun of the Dead brought comedic zombies (or zombies at all, really) into the mainstream, O'Bannon rightly realized that rotting, wailing, running zombies chasing down a bunch of angry punk teenagers was actually kind of funny, and he played up the humor to maximum effect. Imbuing his story of the resurrecting dead with a wry sense of humor containing sarcasm, slapstick, and Vaudevillian timing, what O'Bannon does that's even more clever is give the horror aspects of his screenplay real bite (sorry), making scenes of marauding hordes of the dead sprinting–sprinting!–after their victims much more terrifying. Forget "removing the head or destroying the brain"–this time the living dead are wholly unkillable, regardless of what you have in your arsenal. "I hit the fucking brain!" growls Burt (Clu Gulagher, Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy's Revenge) after putting a pick-axe into a zombie's skull without it doing a thing. By comparison, Romero's slow-moving, easily killable ghouls were barely a threat. O'Bannon ups the terror, but brings the humor with it. (He claims that naming his two leads Burt and Ernie was entirely coincidental, and he was completely unaware of the duo's long-running residence on Sesame Street, but when two of the film's hapless and doomed paramedics eaten by the living dead are also named Tom and Jerry, you really have to wonder.)

During one scene where they look to Night of the Living Dead to provide answers on how to kill the undead (destroy the brain!), Freddy (Thom Matthews, Friday the 13th: Part VI Jason Lives) asks, "What do doctors use to crack skulls with?" Frank (James Karen, Poltergeist) answers, "Surgical drills!" at the exact moment Burt re-enters the scene holding a pick-axe. Humor like this seems very broad, especially when compared to today's standards in horror films where someone would stop to ironically muse on the meta of the conflict before continuing on, but it's a sadly extinct, wry sense of comedy that, for anyone who has ever seen or read an interview with Dan O'Bannon, senses was a part of his genetic makeup.

O'Bannon, famously, opted to make his take on this somewhat new zombie universe more humorous in an effort to avoid treading directly on territory he felt strongly was owned entirely by Romero. But at the same time, in lieu of this respect, you get the sense that O'Bannon was also having a hell of a time sending up this genre that, maybe, people shouldn't be taking so seriously after all. After all, Romero's zombies were flesh-eaters, taking their sweet time in stripping flesh and entrails from their victims for a warm feast–this is intrinsically frightening. O'Bannon's zombies seem only interested in braaaains, which they shouted repeatedly while chasing down a victim. While the image of them chowing down on brains is still the stuff of nightmares, everything leading up to a kill is kind of a cartoon.

It's during a routine training session at Uneeda Medical Supply where Frank unleashes the zombie-resurrecting 2-4-5 trioxin gas from barrels stenciled with Property of the United States Army, which douches himself and his new hire, Freddy, in the necromancing fog slime. This is part of the overall palpable sense of distrust O'Bannon shows toward the American military throughout, beginning with Frank refuting any inference that the barrels containing infected corpses might leak (even though they do), and ending with the very downbeat and cynical finale which sees the military dealing with their "missing Easter eggs" in the only way they know. And in between, brief scenes with Colonel Glover (Jonathan Terry) present him as a dry, bitter, and disillusioned man who orders nuke strikes like other people order pizza.

But even out of this anger comes further opportunities for humor. When Freddy asks why those tanks of diseased bodies ended up in the basement of a medical supply warehouse, Frank smiles slyly and says, "Typical Army fuck-up," with the word "typical" giving his response its meaning, as if it were part and parcel among the many other Army fuck-ups worth mentioning that deal with the misdistribution of dead bodies. After shit hits the fan and one character logically suggests that they call the number stenciled on the side of the tank, Burt looks besides himself as he demands, "Do you think I want the goddamned Army all over the place?," as that would be worse than the recently resurrected corpse screaming and pounding on the inside of the walk-in freezer.

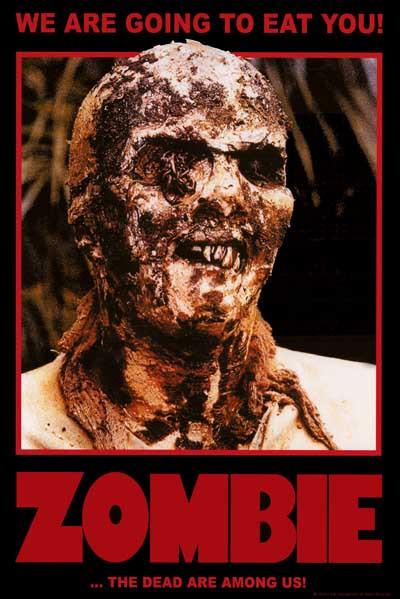

The Return of the Living Dead's use of somewhat dated and primitive techniques for special effects is the thing, among many things, which make the film so lovable and enduring. Seeing the Tar Man or the female half-a-corpse strapped to the table opening their mouths once, but somehow emitting multiple syllables, of course doesn't look all that convincing. It makes no sense that their very tongueless and lipless mouths can emit 'S' and 'P' sounds. But it somehow goes along with the spirit of the film, which leans heavily on, "Fuck it, let's just have fun."

After all, have you seen the poster?

They're back from the grave and they're ready to party!

Calling The Return of the Living Dead the greatest zombie film of all times feels like an insult to George A. Romero, being that its existence directly stems from his 1968 classic Night of the Living Dead, but also because O'Bannon avoided doing a more serious-minded zombie film, as he felt it would tread too closely on Romero's territory. However, where Romero was able to carry respectability through his zombie series up to and including Day of the Dead (which was pulverized at the box office the same year by O'Bannon's film), multiple attempts to sequelize The Return of the Living Dead–either maintaining the humor or not–proved that it wasn't so easy. (This more than includes Return of the Living Dead II, which tried so hard to be its predecessor that it not only brought back James Karen and Thom Matthews to play different characters who "feel like they've been here before," the sequel even ripped off its predecessor's incredible opening music, known as the Trioxin Theme.) Inspired by what came before, The Return of the Living Dead was lightning in a bottle, made from a perfect combination of sensibilities, willing performers, and grisly special effects. Though it may not enjoy the same critical or historical reputation as its mama, Night of the Living Dead, it's easily just as beloved...but only by people with braaaains.