The below is an archival piece that was originally published on Cut Print Film in 2016, parts of which have since been excerpted in author Dustin McNeill's book, Further Exhumed: The Strange Case of Phantasm: Ravager, the sequel to Phantasm Exhumed: The Unauthorized Companion. It has since been slightly updated, and concludes with a full review on the article's mooted Phantasm: Ravager.

[Contains spoilers for the Phantasm series. Run!]

“Seeing is easy. Understanding… that takes a little more time.”

— Phantasm III: Lord of the Dead

Since 1979, the Phantasm series has been both entertaining and baffling the brave and dedicated few willing to traverse its bumpy path of seemingly plothole-infested mythos and attempt to comprehend its bizarre storytelling. The original Phantasm, released at the height of the ’70s, came out of nowhere. Along with Phantasm, the decade had blessed horror-loving audiences with its most important additions since the Universal monsters of the 1930s: The Last House on the Left, The Exorcist, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, Black Christmas, JAWS, Carrie, The Omen, Suspiria, Dawn of the Dead, Halloween, and Alien. There’s a reason why this decade is looked upon as the greatest for horror cinema: classics were born, and eventual franchises were in their infancy. The listed films boast more than fifty sequels, remakes, and television series, and to list the countless “homages” (read: rip offs) that would soon follow is nearly impossible.

However, as groundbreaking as each of these films may have been, each was linear, told in a traditional narrative, and except for Suspiria, were mostly decipherable. In a scenario that would soon become paramount to the horror genre, the films’ antagonists were clearly defined—be it flesh-and-blood monsters, undead, or from hell itself—and the conflicts, though greatly varied, unfolded in a straightforward fashion:

Michael Myers kills his sister one Halloween night for no particular reason. Fifteen years later, he returns home to kill again.

Carrie White, a social outcast at both school and home, begins to develop telekinetic powers in conjunction with her maturing sexuality.

The Sawyers, a family of inbred psychopaths, are economically hurt by the dismantling of their only means of support—the local slaughterhouse—so they turn to the next most viable source of food: human flesh.

To our protagonists who either eluded or subjugated their respective boogeymen, their confrontations seemed culled from their darkest nightmares...but did the films themselves feel like a nightmare? Were they filled with surreal images and out-there concepts? Did characters flee strange mechanical objects with lives of their own? Did they encounter otherworldly biological entities capable of changing physical form? Nope—not till 1979.

To the religious, the events of The Exorcist or The Omen aren’t unbelievable. To the Darwinian, the events of JAWS or Carrie could possibly happen. And let’s face it: if we’re playing fast and loose with history, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre already happened, while The Last House on the Left happens every day, in one form or another. But Phantasm was a strange journey for anyone watching, and it was unlike anything else the world had ever seen. Oh, sure, by this time, David Lynch’s Eraserhead was already two years old and had caused its audience to murmur “what the fuck?” on their way out of the theater, but unlike Eraserhead, Phantasm wasn’t cavorting as an art picture. Trailers sold it as some goofy B-movie about a killer mortician: young adults were stabbed in cemeteries, sex was had, breasts were flashed, and the young hero of the story was routinely dismissed by those around him. They were familiar tropes in familiar surroundings. To judge it from its marketing alone, it was just another “dead teenager” flick. Phantasm wasn’t supposed to be as surreal as it was…it had no right.

But it was. After gaining distribution by Avco Embassy, Phantasm would go on to gross $12 million ($43 million when adjusted for inflation) on its budget of $300,000. And these paying audiences were simply not prepared for the strange story unfurling before them.

Solidifying Phantasm’s individuality is its bizarre blending of genres: straight-up supernatural horror peppered with elements of science fiction, fantasy, and bits of slasher. The hero is not an older man, distinguished with a PhD, nor a Roman Catholic priest armed with a briefcase of holy waters, religious texts, and his faith. The hero is thirteen-year-old Mike Pearson, mourning his recently deceased parents and living with his older brother, Jody. Precocious to the point of recklessness, he speeds on his motorbike across cemetery grounds or wanders through the main street of his town checking payphones for lost change...but he also investigates grave-robbing dwarves, mindless mortuary slaves, cut-off fingers that morph into monstrous insects, and self-driving hearses. And he does so because of what he sees one day while spying on a funeral for the film’s opening victim: the mortician—a very Tall Man—picking up the departed’s coffin by himself and sliding it easily back into the hearse before driving off with it. Understandably, Mike is perplexed, and he knows he’s got to find out everything he can about the owner/operator of Morningside Cemetery.

Phantasm then mushrooms into a wonderful cacophony of late-night escapades bathed in the dreamlike imagery by a young and unproven but inexplicably masterful Don Coscarelli. Over the course of two production years, an epic three-hour tale of good versus evil was completed, which was then pared down into the ninety-minute cut that lives today and which is mostly responsible for giving the film its strength. Scenes aren’t so much seamlessly attached with graceful fluidity as they are hastily stapled together, with a continuity-be-damned aesthetic accidentally achieved but entirely appropriate. Such juxtaposition would be jarring and distracting for your more traditional horror romp, but it felt right at home within the dreamy confines of Phantasm, where by design everything felt just the least bit…off. Random characters are introduced, such as Jody’s friend, Toby, or Myrtle, the Pearson house keeper, never to be seen again. Any sense of a physical timeline is nearly incomprehensible. Day becomes night becomes day, while offering no concrete idea as to how much time is passing. Such observations would be considered flaws in a film with a more traditional construct, and perhaps Phantasm itself is flawed for these same reasons, but it’s through these imperfections that the film embraces perfection.

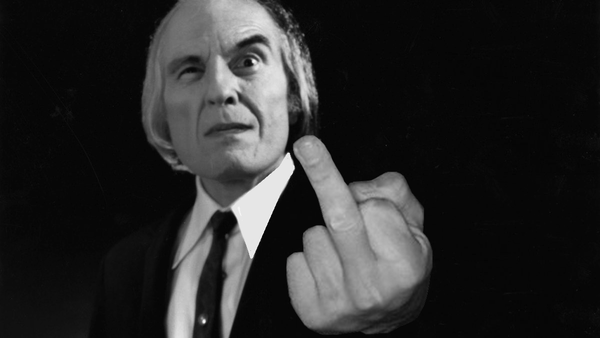

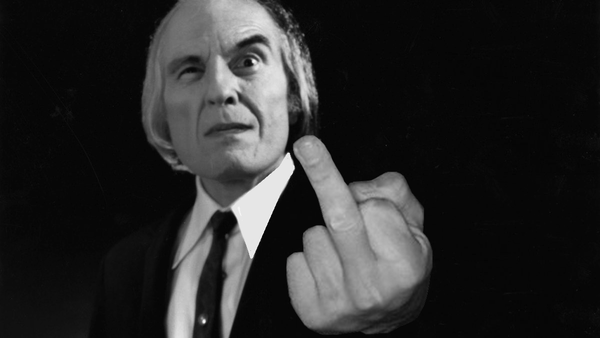

As Mike dives deeper and deeper into the Morningside mystery, he learns some disturbing facts about the Tall Man: he might very well be an alien from another planet, or a demon from another dimension. The brown-robed dwarves often seen scurrying around the marble floors of the mortuary are his pint-sized slaves—corpses harvested from the cemetery and mausoleum. And don’t forget the silver sphere, equipped with an array of knives and drills, which patrols the halls of the mortuary with a reverberating hum—an image that would soon become synonymous with the Phantasm series.

Largely a parable about death, Phantasm presents a fascinating character study of an adolescent stunted by his overnight transformation from child to adult in the wake of parental demise. Forced to become a man based on sheer necessity, Mike has no choice but to investigate all the creepy goings-on at Morningside Cemetery by himself, much in the same way he has no choice but to, going forward, navigate a life lacking parental guidance—and both for the same reason: because except for his older brother, who is ready to blow town at a moment’s notice, Mike has essentially become orphaned during the most formative years of his young life. Such a presentation of a tragic figure is engaging and saddening in equal measures, and in the same way Ray Bradbury had the ability to convey intangible but detectable sadness obscured by clouds of nostalgia, Coscarelli writes and shoots Phantasm through the eyes of a young boy who on the surface is brave, forthright, and resourceful, but who on the inside is heartbroken over the death of his parents and terrified that he’s going to wake up one morning and find that his brother has abandoned him. If you sit down with an auditory eye and look beyond Phantasm’s more typical horror front, you’ll notice that the film is constructed by sequences in which the two brothers repeatedly separate: Mike leaves Jody to investigate; Jody leaves Mike to investigate; Jody locks Mike in his room; Jody drops off Mike at a friend’s antique store—and after every single time the brothers aren’t together, something awful happens. That right there is the heart of Phantasm: the fear of letting go.

Even with these thematics aside, this approach also allows Phantasm to show off some refreshingly antiquated political incorrectness, depicting a thirteen-year-old as swigging beer, driving muscle cars, shooting guns, building makeshift explosives, and cursing up a storm. (Speaking of political incorrectness, one of the most memorable lines in the film belongs to Jody, who dismisses all the strange noises Mike hears in the garage one night as he works on the undercarriage of the series’ legendary Hemi Barracuda as being “that retarded kid Timmy up the street.” Put this in any modern film and you’ll be issuing apology press releases long after it stops trending on Twitter.) What seems like a minor point to include in the midst of a discussion on thematics is actually fairly significant, as it somewhat summarizes the legacy of the Phantasm series in general: they just don’t make ’em like this anymore, and it’s getting harder and harder to do so.

Immediately following the alleged resolution of the story, in which the Pearson brothers trap the Tall Man in an abandoned mine with a multitude of heavy boulders, the film ends with a revelation that would soon become a storytelling cliché:

It was all just a dream.

Mike and Reggie, Pearson family friend, sit by the fireplace as Mike recounts this dream (aka the entire preceding film)—how scary it was, and how realistic it seemed. According to this brand new reality, Jody is dead—killed in a car wreck—and Reggie has become Mike’s guardian. Such a revelation, however shocking, remains secondary to another realization: Reggie, whom we had all witnessed killed in the climax of the film, is not only alive and well, but refuses to recognize the Tall Man as anything other than a figment of Mike’s imagination. He shows no signs of remembering the battle at Morningside Cemetery, nor the (mortal?) wounds he suffered. Mike fervently believes the Tall Man is real, but with Reggie being there when he otherwise shouldn’t, audiences exhale and settle back in their seats. It must’ve been a dream, after all—a nightmare concocted by Mike’s tortured mind to refute his brother’s death. Reggie suggests they get out of dodge for a while, so Mike runs up to his room to pack. It is there he finds the Tall Man, who it seems is real after all. But to what extent? How is it that the Tall Man can actually exist, yet nothing we had previously witnessed in the film seems to have happened? How can Mike know all about the Tall Man if it was all just a dream? Did anything we see truly take place? There is no time to analyze the enigmatic revelation of the Tall Man’s existence, as Mike is soon attacked and pulled through his closet mirror, screaming into the darkness beyond. And the amazing Phantasm theme—one which gives Halloween‘s own a run for its money—kicks in as the screen cuts to black.

It would be easy to point fingers and call this a cop-out ending, and if it had been any other film, it would be right to do so. But as an ending following Phantasm's bizarre occurrences, it was fucking poetry.

Audiences’ minds were blown and critics were baffled. How do you properly critique a film that could either be an artistic dreamlike masterpiece, or a muddled mess of incoherence—a film originally designed to be three hours, but which was whittled down into half that running time? What do you do with a story that, according to its own ending, never even happened…but at the same time…did?

Following these questions, the legacy of Phantasm was born. Three sequels would eventually follow over a span of twenty years, each written and directed by Coscarelli.

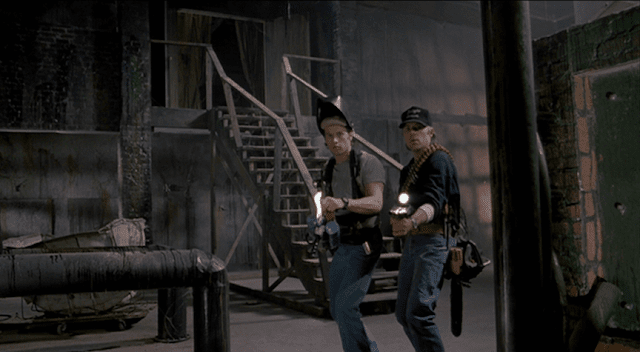

Phantasm II was released in 1988, nine years after the release of the original film. The Aliens of the franchise, Phantasm II is a no-holds-barred shoot ’em up that turns the action up to eleven. Because it was the only Phantasm film to receive a wide release from a major studio, artless suits ordered Coscarelli to cut out the dreamy imagery and surreal plot points that gave the original its reputation (and identity). Coscarelli obliged for the sake of his production. While still a great film, and cited by many as their favorite entry, many of the ideas Coscarelli wanted to include were left on the cutting room floor—along with actor A. Michael Baldwin, replaced by James LeGros at studio’s orders—and that’s a damn shame, because the absence of both are felt and missed.

Phantasm III: Lord of the Dead was originally meant to immediately follow Phantasm II, but wasn't released until 1994…and went direct-to-video after a very select release. With Coscarelli promised full artistic freedom this time around, the dreamlike state of the series returned in full force…and brought with it a lot of strange Evil Dead 2-esque comedy, as well as the very welcomed return of A. Michael Baldwin. While this entry turned off some longtime phans, Lord of the Dead introduced a lot of important ideas that carry through to the next entry and rewrite the relationship between Mike and the Tall Man as far back as the first film.

Flash forward to the following year: 1995. In a very strange and unexpected development, and now forever embedded in the Phantasm's series bizarre saga, screenwriter Roger Avary, fresh off his Oscar win for his work on Pulp Fiction, proudly announced he was going to write the be-all, end-all, kick-ass conclusion Phantasm sequel that the series deserved. Originally titled Phantasm 1999, then Phantasm: Millennium; then Phantasm: 2012 A.D.; then Phantasm 2013; and finally Phantasm’s End, the story was large in scope and introduced several new characters to fight alongside Reggie, the main-man who’d organically inherited the role of hero throughout the Phantasm series. In Avary’s script, the majority of the U.S. had been turned into a quarantined contaminated zone where the Tall Man thrived and continued his scheme to take over the world, with a legion of the undead under his power. While Coscarelli was enthusiastic about the story, he was unable to find a studio willing to finance such an ambitious project birthed from what had long been considered a cult series. Coscarelli’s consolation prize was to write his own sequel script, which would become the official fourth installment of the franchise, Phantasm IV: Oblivion, hoping to shelve Avary’s script for later use, and perhaps for the series’ final bow.

Phantasm IV: Oblivion was released in 1998 and for a long time seemed to signal the end of the Phantasm series. Every subsequent sequel following the original’s release found Coscarelli forced to work with diminishing budgets, relegating him to try another tactic for this particular entry: sifting through that ninety minutes of unused footage from the original Phantasm shoot to find cut scenes or new revelations that could add to the mythos, which he then weaved into a fresh story—one which found Mike Pearson hurtling alone into the desert in an attempt to escape the Tall Man-induced transformation happening inside him. Failed suicide attempts, memories thought lost, and a last minute deus ex machina involving Mike’s brother, Jody—all allowed Coscarelli to dip into the past and unearth footage to carry his saga to its conclusion. No ongoing series had ever, and likely will never, attempt such a maneuver.

Phantasm IV: Oblivion successfully returned to the nightmarish elements and intimate restraint of the first film, but even in its attempts to continue explaining the myth of the Tall Man, would only produce more questions. Despite its very finite ending that definitely stated “this is the end of the journey,” some phans were left feeling unsatisfied, and thanks to that conclusion’s slight tease of further adventures, they hoped more would soon come.

Reggie Bannister, the hot-as-love bad-ass who would go on to become the face of the series—even more so than the Tall Man himself—told Fangoria on the release of Phantasm: Oblivion: “This could very well be the last one…but then again, every one could have been the last one.” For years following the release of the “final” Phantasm, phans hoped for one last battle between good and evil—and it’s one Coscarelli had been diligently promising ever since Oblivion hit video. Much like the Tall Man himself, the prospect of a Phantasm V just wouldn’t die.

Following the release of Oblivion, rumors of Phantasm V infected the Internet for years, none of which came to fruition:

- Roger Avary’s Phantasm 1999 script would finally be dusted off for the epic conclusion the series deserved.

- Ice cream man and Phantasm hero Reggie Bannister had written his own Phantasm script centered around two remaining cities in an otherwise barren wasteland of the United States.

- Bruce Campbell would star in a Phantasm V variation…alongside a monkey.

- Writer Stephen Romano had pitched Phantasm Forever, said to begin with Mike waking from a years-long coma to find he’s being treated by Dr. Morningside, who in actuality is the Tall Man in disguise, as well as a scene including a confrontation between the two actors to have played Mike throughout the series: A. Michael Baldwin and James LeGros.

- Phantasm V wasn’t going to happen at all, but instead the series would be remade into a new trilogy by New Line Cinema.

- Phantasm V would happen…in 3D.

- Phantasm V would be made…intermittently, in the form of webisodes called “Reggie’s Tales.”

Throughout these misleading years, Coscarelli felt obligated to keep the lighthouse burning for another entry, and in an unprecedented move, actually told a major studio, “No, you can’t remake Phantasm because,” basically, “you’ll fuck it up.” Being not just the creator of the series but the father of the phans meant having to go to bat for them while delivering years and years of bad news. He grew used to releasing public statements that dismissed any and all rumors of an impending Phantasm V, and with each denial, phans’ hopes were crushed just a bit more. He also didn’t help by adding fuel to the fire when he released this Alamo Drafthouse tribute video (in 2008!), which featured the director editing a potential teaser scene from a read-through of an unproduced Phantasm V script.

Speculation immediately went through the roof.

It was happening!

Phantasm V was finally on its way!

And then…nothing happened.

Time went on and the possibility of a proper Phantasm V dwindled from inevitability to despair. Coscarelli continued to openly state that following his work on John Dies at the End, he wanted to “get something going in the Phantasm world,” having admitted to writing not just one Phantasm sequel script, but several, and stated, “it would be a shame not to realize any of that.” But, as has always plagued the Phantasm series up to this point, financing continued to be an issue, not to mention that phans had gotten used to Coscarelli’s non-committal hopeful statements and were sadly accustomed to dismissing them.

And then, in March of 2014…

It. Finally. Happened.

The teaser trailer for Phantasm V, called Phantasm: Ravager, was released. It exploded across the internet like a sawed-off four-barrel shotgun, causing all kinds of celebration, starting with the phans and ending with the most unlikely of sources. In a moment of utter surrealism, it was enthusiastically picked up by Entertainment Weekly, a move that didn’t mesh at all with their “we love anything that’s popular!” philosophy. The trailer, which featured global destruction, silver spheres the size of houses, and the return of Mike, Reggie, Jody, the Tall Man, and even the Lady in Lavender, not seen since the first film), naturally sent everyone into a fan-geek blast of exhilaration.

That exhilaration only lasted so long, because a disturbing new development came to light: Coscarelli had opted not to direct the newest installment, having handed over the reins to longtime collaborator David Hartman, an unproven director. This served as a somewhat disappointing blow to phans who shared the mindset that whatever Coscarelli had begun in 1979, it would be up to him to finish. That he remained on the sequel as a co-writer of the screenplay and a very hands-on producer helped to allay some of those fears, but for some, it wasn’t enough. Though phans were thrilled to receive any iteration of a new Phantasm film, some approached Ravager with a great sense of caution, and in the same way they were hesitant to laud Roger Avary’s unmade Phantasm script: because no matter how strange and unorthodox the Phantasm journey had been, and despite all of the questions posed since that first night-drenched hearse ride back in 1979, each entry had been written solely by Coscarelli. Because of this, some of the more ardent phans believed that whatever fragmented story he had been telling for the last forty years belonged exclusively to him, and to have handed off the mythos to another writer seemed very wrong. To some, it would've been better to get a shitty Phantasm V written/directed by Don Coscarelli than a fantastic Phantasm V written/directed by anyone else.

Still, the explosion of excitement the trailer caused couldn’t be ignored. The film wasn’t just in production, but had been fully shot in secret over the last few years. (Its existence can be tracked back at least as far as John Dies at the End, in which one character has a DVD for Phantasm: Ravager sitting next to his television.) Ravager was done and in the can, so it seemed like only a matter of time before solid release plans were formally announced.

More than one year later, the wait continued. Things were disconcertingly quiet over in the Phantasm camp, as the last word on the subject had been that Coscarelli and co. were “still trying to find distribution.” Speculation soon began on who would step up, with Anchor Bay/Starz and Shout! Factory being touted as the likeliest of candidates, being that they’ve both released video editions of the previous films in the past. Other rumors suggested Image Entertainment had been flirting with releasing Blu-ray editions of the Phantasm series, and so by default also had their hat in the ring.

And then in December of 2014, Coscarelli and Hartman released a lovably dorky video teasing a bit more footage from the new entry, as if to touch base with phans and say, “Yeah, we know this is taking a while” and “No, we haven’t forgotten about the damn thing.”

Some interpreted this inability to secure distribution pointed to Phantasm: Ravager being an artistic disaster, and the longer it took for the film to see the light of day, the harder that fear became to refute. After all, why release a teaser trailer so soon in advance if the filmmakers weren’t confident it was close to completion and could easily find a home? (“Warning shots are bullshit,” Jody says while handing Mike a gun in the first Phantasm, and the phrase seems ironically appropriate.) That Ravager had issues requiring some minor-to-major post-production finessing were not an absurd assumption to make, but others preferred to think (and hope) that Coscarelli was instead exhibiting an inordinate amount of care over what may very well be the final Phantasm film. (Rumors suggest he’d already been offered a distribution deal and turned it down.) Sixteen years came and went between the release of Oblivion and Ravager's teaser trailer debut. Phans had already waited that long, and depending on which of them you asked, some said they could wait just a little bit longer…while others said they’d waited long enough. A lot of time had been lost thanks to the myriad of difficulties Coscarelli endured in trying to secure financing in the past, and on locating a studio with the vision and balls to take the risk on a lesser-exposed property with out-there concepts. That Sharknado and The Human Centipede have each become a trilogy, the former in just three years’ time, yet it’s taken nearly forty years for Phantasm to reach its fifth film, is at the least disappointing and at the most offensive.

With Ravager likely being the final installment of the long-running series (though Don recently had the loving audacity to muse on Phantasm VI), all phans were hoping it was the definitive sequel they’d been waiting for, and so certain expectations were in place. Series stalwarts know Coscarelli likes to fuck with his audience — to make them question nearly everything they see, and leave them wondering what was real. For nearly forty years, he’s triggered multitudes of questions. With the series' swan song, phans were hoping for some answers — phans who had been aching to find out just what the hell was going on in this universe.

And that's where it got dangerous.

Leading up to Phantasm: Ravager's release, I was hoping it would be a satisfying finale. I was hoping it felt familiar despite being entirely brand new. I was hoping it would look to the first and fourth entries for the heart of its story; to the second for an inspiring dose of action and that perfect blending of humor and terror; and to the third for a 100% free-to-do-whatever independent mentality. I was hoping that the final entry would successfully straddle that line between poetic ambiguity and satisfying revelation, because phans know Phantasm thrives on mystery. So was it finally time for some closure? Should phans finally know if everything Mike had seen and experienced been real, or if it was all just his psychosis — an escape into the muddied, morbid world he’s created inside his head to rebuke his own mortality?

Maybe it would've been best never knowing that for sure...but the sequel had finally arrived.

No horror fan has ever had to endure such a long wait between sequels as Phantasm phans. Making it harder is that we can’t liken Phantasm to a more traditional horror series like Friday the 13th or A Nightmare on Elm Street. The simplicity of those films, though they vary in quality, don’t create the same kind of angst in between entries. Mini-arcs, one-offs, ret-cons, or now, reboots, comprise those series. Neither series told one overarching story, or featured the same creative team or repertoire of actors. And none of them made their fanbase wait eighteen years for the concluding entry.

Phantasm did.

Begun in 1979 as just a creepy, low budget horror tale set against the night, which found the Pearson brothers and their family friend, Reggie, squaring off against an evil from — another dimension? planet? world? time? existence? — their nightmares, Phantasm was never meant to become what it became. And no one seemed more surprised by that than its creator, Don Coscarelli.

Picking up where Oblivion left off (kind of), Ravager finds Reggie (Reggie Bannister) wandering the desert, his ice cream suit bloodied and torn from an unseen battle, looking for his ‘Cuda, or his friend Mike (A. Michael Baldwin), or a friendly face. But it also finds him in a nursing home, sat in a wheelchair, being comforted by Mike, who is telling him that he’s been diagnosed with dementia — that these “stories” about The Tall Man are, this time, Reggie’s delusions. And there’s yet another Reggie wandering his own desert, in his usual flannel and jeans garb. There are multiple Reggies, multiple Mikes. What is happening? How is this possible? Because much of this footage had been originally shot as the basis for webisodes called Reggie’s Tales over the course of 6-7 years, which were then co-opted by Ravager. (If you're wondering why Coscarelli didn't serve as director on Ravager, it's because these webisodes were all directed by special effects guru David Hartman, which weren't originally intended to be folded into a feature sequel.)

In what was promised to be the concluding chapter that would answer nearly all the questions posed by the series, Ravager is strangely experimental — to the point where the physical manifestation of alternate dimensions colliding with each other, which up to this point in the series had been merely theoretical, feels almost as if it were manufactured to purposely conjure confusion. The Phantasm series has always been willing to screw with its audience, leaving them to wonder what was real and what wasn’t, and it was through the films’ construction where that confusion felt earned and all part of the plan. But Ravager feels intent on flat-out mystifying its audience, injecting a sort of series ret-con that never feels like it were destined, but more like a response to the slow, organic change that has carried through the entire Phantasm series so far — the evolution of Reggie from supporting character to lead hero. Ravager suggests that the series has always been about Reggie, and though Reggie Bannister is a wonderful human being, and his on-screen Reggie is the kind of loyal, loving, guitar-strumming hippy friend we all wish we could have, the series was never about him. It was about the strange link between Mike Pearson and The Tall Man. How was it that this thirteen-year-old kid (at first) had the power and the knowledge to best an evil being from another world? And what did The Tall Man mean when he said he and Mike “have things to do” during Oblivion? Indeed, every entry of the Phantasm series reinforced the idea that there existed a special link between Mike and The Tall Man. Ravager, except for a single line during a confrontation between Reggie and the infamous tall boogey-alien, seems to have forgotten all that. Mike, though Baldwin is featured somewhat prominently, comes off as an afterthought — almost like a plot hole that Coscarelli and new director Hartman had to contend with in order to satisfy “the Reggie story.” And that, more than anything else about Ravager, feels very wrong.

Like all the other films in the series, Ravager is very ambitious. With eyes larger than its budget, Ravager wants to be the be-all, end-all flashbang ending to the series that the phans have been clamoring for since 1998 (and which seems to have borrowed elements from Pulp Fiction co-writer Roger Avary’s unproduced Phantasm’s End script). The problem is whatever budget Coscarelli and co. had couldn’t support that ambitious vision. From a production standpoint, Ravager feels instantly at odds with the series; its obvious digital shoot doesn’t mesh with the previous shot-on-film predecessors, including the lushly photographed Oblivion. None of the CGI, which is relied on far too often, looks convincing, and the sequences showing widespread hell-like destruction across entire cities look straight out of a video game. (By comparison, the original film’s technique of literally throwing silver sphere Christmas ornaments down a mausoleum hallway or hanging them from fishing line looks a damn sight better. It’s ironic that Coscarelli and J.J. Abrams embarked on a two-year journey to restore Phantasm and digitally erase all the “mistakes” and “tricks” with the special effects that had bothered Coscarelli for years — including that fishing line — but apparently he’s totally fine with the crappy effects in Ravager.)

The phan in you will want to ignore all this; the love you have for the series will want you to push it all aside and say, “They’re really going for it, aren’t they? Good for them!” But the phan in you also recognizes that, after eighteen years, you deserved better. You deserved something with a look beyond that of a Sy-Fy Channel original, or a production from The Asylum. You deserved Coscarelli being in the trenches with his audience and helming the last entry of the series he created, and for which he oversaw every entry. But really, what you deserved was Coscarelli deciding, “If we can’t do this right, we’re not going to do it at all.”

The Phantasm series has always posed a lot of questions, but Ravager is intent on posing all the wrong ones. Why reduce The Tall Man’s role from lead horror villain to a quasi-philosophical bargainer whom none of our protagonists seem especially fearful of confronting, relegating his role to man who lays in a bed or stands around? (He doesn’t even backhand anyone across the room! That’s, like, his signature move!) Why give this entry’s destruction of The Tall Man to an inconsequential character who was never involved in the series until this entry, robbing Mike and Reggie of their own final confrontation? Why bother bringing back Bill Thornbury (the series’ Jody Pearson), Kat Lester (Phantasm's Lady in Lavender) and Gloria Lynne Henry (Phantasm III’s beloved Rocky) for…that? (And why rob the phans of an on-screen reunion of Rocky and Reggie, being they spent all of Phantasm III together? They're in the same car but never share the same shot once. I mean, what the fuck!) Perhaps the most concerning of all: why has Coscarelli forgotten that Mike Pearson is the main character — the trigger around which the entire series had been constructed?

The Phantasm series has always posed a lot of questions, but Ravager is intent on posing all the wrong ones. Why reduce The Tall Man’s role from lead horror villain to a quasi-philosophical bargainer whom none of our protagonists seem especially fearful of confronting, relegating his role to man who lays in a bed or stands around? (He doesn’t even backhand anyone across the room! That’s, like, his signature move!) Why give this entry’s destruction of The Tall Man to an inconsequential character who was never involved in the series until this entry, robbing Mike and Reggie of their own final confrontation? Why bother bringing back Bill Thornbury (the series’ Jody Pearson), Kat Lester (Phantasm's Lady in Lavender) and Gloria Lynne Henry (Phantasm III’s beloved Rocky) for…that? (And why rob the phans of an on-screen reunion of Rocky and Reggie, being they spent all of Phantasm III together? They're in the same car but never share the same shot once. I mean, what the fuck!) Perhaps the most concerning of all: why has Coscarelli forgotten that Mike Pearson is the main character — the trigger around which the entire series had been constructed?

But it’s not all doom and gloom. There are sequences and moments in Ravager that really work. Reggie’s very first non-voiceover line of dialogue will have you laughing out loud, and his ongoing struggle to get laid concludes in the most appropriate way. The bond between our characters, especially Reggie and Mike, is as strong as ever. And how could it not be? They’ve been real-life family since before the first frame of the first Phantasm was ever shot. That final “real world” sequence between Reggie, Mike, and Jody — even though it feels at odds with the overall series story — still works on an emotional level, because we have been with these characters for forty years; we’ve grown older just as they’ve gown older, but throughout this time, we never lost touch with them, and we tagged along during their night-time adventures in Morningside, or Perigord, or Holtsville, or Death Valley.

In keeping with that longevity, seeing Angus Scrimm embody The Tall Man one last time (it’s fitting that his swan song was a return to the role which has earned him infinite infamy) is a delight, especially being that he may be older (although the film digitally de-ages him), but he hasn’t lost his edge, or his grasp on the character. Composer Christopher L. Stone has created the best musical score of the series since the first film, which somehow doesn’t sound cheap, but rather large, flourishing, and wide reaching. Hartman stages some moments of genuine eeriness as well as some exciting sequences, most of them having to do with high-speed chases on desert highways between the series’ beloved ‘Cuda and a swath of brain-drilling silver spheres. The scene set in the hospital that sees the “real” world and the possible dream world colliding with each other, with Mike tossing Reggie a gun to aerate the droves of gravers attacking him — while also fleeing reality — was beautifully done. And the ending — not the “real” ending, but the one that, oddly, seems more optimistic — was strikingly poetic, doing a fine job summarizing what the series has always been about: brotherhood, loyalty, and defiance in the face of death.

Was Phantasm: Ravager worth the wait? That’s a hard question to ask, and an even harder one to answer. Because at this point, it’s the phans who own the Phantasm series and no one else — not mainstream audiences, not critics, and not the casual horror crowd. Everything about the series is beyond those demographics’ criticisms. It’s up to the individual phan to determine whether Ravager was a fitting end to the long-running series, or a blown opportunity for the catharsis that Oblivion had the decency to temporarily provide, even within its fog of ambiguity. For this particular phan, eighteen years is a hell of a long wait to end up with something like Phantasm: Ravager.

Was Phantasm: Ravager worth the wait? That’s a hard question to ask, and an even harder one to answer. Because at this point, it’s the phans who own the Phantasm series and no one else — not mainstream audiences, not critics, and not the casual horror crowd. Everything about the series is beyond those demographics’ criticisms. It’s up to the individual phan to determine whether Ravager was a fitting end to the long-running series, or a blown opportunity for the catharsis that Oblivion had the decency to temporarily provide, even within its fog of ambiguity. For this particular phan, eighteen years is a hell of a long wait to end up with something like Phantasm: Ravager.