Hollywood is in love with

portraying a world either on the brink of extinction or already long dead. And

these types of films have only gotten bigger in scale since the advent of CGI.

Now it isn't just meticulously constructed models being burned with a

flamethrower or drowned in frothy ocean water. It's entire cities, or

countries, or planets. Streets melt or collapse into sink holes; skyscrapers

disintegrate into piles of twisted metal; bridges belly-flop into the oceans

below. Spoiler alert: as the technology has improved to realistically destroy

civilization itself, the magic of how a world of make-believe was brought to

life has decreased, skewing these weakening apocalyptic stories to such a

degree that darkened-theater demands of, "How did they do that?" have

since been answered by, "Computers, idiot." The rapidly improving

visual effects industry may be bringing the impossible to life, but it's doing

so at the expense of why film exists in the first place: human connection.

During the 1980s, this

apocalyptic fascination somewhat took a backseat to John Hughes and the many

action and horror franchises that were running rampant and attracting most

theatergoers' attention. Except for Max Rockatansky, no film characters were

keen on watching social order fall around them before wandering around a

desolate desert landscape. Everyone just wanted to do cocaine and wear pink

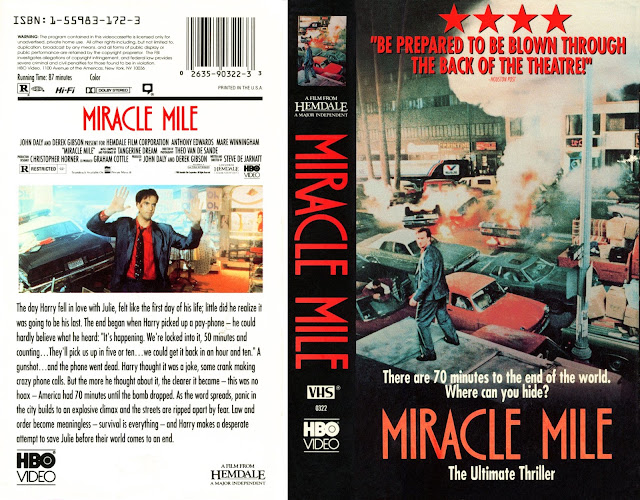

sunglasses and listen to Wang Chung. This is one of the things that makes Miracle Mile so notable, although it's

not the only thing. What makes Miracle

Mile a film worth remembering over thirty years after its theater debut

is how much of it still feels so relevant, and how at-ground-zero it puts the

audience at the conception of nuclear destruction. One of Miracle Mile's

greatest strengths is that once Harry (Anthony Edwards, Pet Sematary Two) answers that damned ringing payphone and

learns nuclear warheads will strike Los Angeles in fifty minutes, the remainder

of the film plays out in painstaking real time. It's at the very diner where

Harry was supposed to meet Julie (Mare Winningham) for their date where he relays the news of his

revelation to the other diner patrons. Most of them are quick to wave off his

claims until one of them, well-connected and fully well knowing this was a

possibility, gets on her mobile phone to confirm Harry's claims. Once she does,

the film's collection of tremendous supporting characters all begin working

together to exact the quickest evacuation of Los Angeles they can muster: who

will gather the food, who will navigate, and for the love of everything, does

anyone know a helicopter pilot?

It's watching Los Angeles' very

slow, but also very rapid, descent into chaos that enables Miracle Mile to pack such a punch. And during its 1988 release

date, the Cold War was still very much in the forefront of American minds. It

seemed like nuclear warfare was a dangerous possibility nearly consistently,

and many people were fearful that the bombs could drop at any time. But it's

also watching Harry hopping over cars, fleeing gunmen, ducking from explosions,

and depending on people he's never met to not only find a way out of the city,

but somehow also locate Julie, a perfect stranger with whom he's in love, in

the middle of all that madness.

Getting back to an earlier point,

and being that this was 1989, Miracle

Mile’s bird's-eye view of destruction is brought to life all through the

use of practical and in-camera effects, depending very scarcely on opticals. CGI at its height has brought entire characters to life, be it Gollum

or Caesar or King Kong, and after a while, though its creations and its

potential to create can be deeply affecting, it's also doused some of the fear

that filmmakers were once intent on establishing. Nowadays, to set a character

on fire, the actor puts on a green body suit and pretends to run from a flock

of bees, but back then, filmmakers really just set stunt people on fire, and in

spite of how impressive that CGI fire may look, our brains are always going to

filter what's real and what's not. Because of that, their respective potential

impacts are never going to be on an even scale. But this is just one example of

numerous that Miracle Mile presents

so well. As the bombs approach toward film's end and the city begins billowing

in non-CGI radiation heat, you feel that heat against your skin. When the

helicopter crash lands in the ocean and the cab begins filling with real and

black water, your own breath feels stifled. This is Miracle Mile’s power.

What Miracle Mile lives and dies by is its cast, which just might be one

of the best ensembles ever assembled for a film, even if they may not command A-list status - today or back then. Anthony Edwards, at first

glance, seems like an odd choice for a leading man, and his somewhat unconvincing

voice-over that opens the film isn't doing him any favors, but once Miracle Mile settles back and finds its

groove, you begin to realize that the beauty of casting folks like Edwards or

Mare Winningham in the lead roles is because they never achieved the

bigger-than-life baggage that some of their colleagues did. Edwards's plain and

everyday looks helped to sell his character as simply that: a fledgling

musician but nothing more - no one big, no one prominent. He felt real.

The beauty of watching Miracle Mile for the first time,

especially if you're a film buff who for one reason or another has never had

the pleasure, is that every single supporting character is played by a

recognizable face. In a flip-side of Anthony Edwards's everyday looks and stature,

it's in watching an immense collection of actors and actresses playing these

small roles in which they find themselves dealing with the end of the world,

and all the emotional and irrational thoughts that come with it, that really

help to sell the outlandish (but not really!) premise Miracle Mile is selling. To list them all here would be exhausting,

but rest assured each face that pops up will trigger instant recognition. (This

thing even has Denise Crosby! Pet Sematary reunion!)

Miracle Mile manages to combine several different genres -

thriller, romance, sci-fi, even irreverent comedy - to paint a look at the last

fifty minutes of life in a way that's both completely outlandish and entirely

believable. From the wall-faced, blonde-mulleted, bodybuilding rescue pilot (Brian

Thompson) who won't leave his girlfriend behind, to the police-car-stealing

bystander who needs to rescue his sister, to Julie's in-love-but-out-of-touch

grandparents, Miracle Mile pulls off

a magnificent feat: in the midst of city-wide carnage, burning cars, exploding

buildings, and oncoming nuclear war, it puts love at the forefront. Even as the

helicopter whirs to life in front of him, Harry opts to instead turn right

around and head back into the madness for the woman he barely knows, but whom

he already somehow knows he loves. That's something not even CGI can bring to

life.

And I haven’t even mentioned the

tremendous score by Tangerine Dream. The film's intimate opening has the

couple-to-be wandering Los Angeles streets and slowly getting to know each other,

complemented by that ethereal score, but soon, madness descends upon the city,

bringing to life chaos and disorder with it. Cars honk and crunch metal, flames

crackle and whip, errant bullets ricochet off sewer pipes and walls. And the

score by Tangerine Dream, which is not only one of their best (next to

Sorcerer), begins hammering like Miracle Mile’s heartbeat, becoming a

steady tick of the clock quickly running out of minutes.

On those lists that circulate

tantamount to "One Hundred Films to See Before You Die," Miracle Mile should be on there. It’s proven

to be one of the biggest cinematic surprises of my life; if you give it a chance,

it just may be the same for you, too.