Every once in a while, a genuinely great horror movie—one that would rightfully be considered a classic, had it gotten more exposure and love at the box office—makes an appearance. It comes, no one notices, and it goes. But movies like this are important. They need to be treasured and remembered. If intelligent, original horror is supported, then that's what we'll begin to receive, in droves. We need to make these movies a part of the legendary genre we hold so dear. Because these are the unsung horrors. These are the movies that should have been successful, but were instead ignored. They should be rightfully praised for the freshness and intelligence and craft that they have contributed to our genre.

So, better late than never, we’re going to celebrate them now… one at a time.

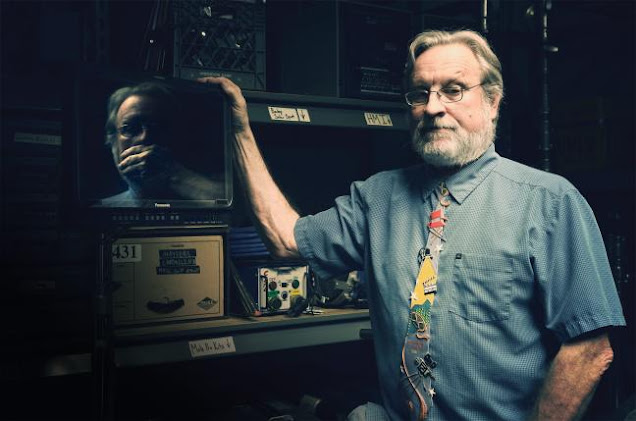

Dir. David Schmoeller

1977

Compass International Pictures

United States

For this edition of

Unsung Horrors, we have a very different beast. Being a genre aficionado, I like my horror in all sizes, shapes, and colors - but I generally prefer a serious tone. I prefer feeling unnerved, and I enjoy the feeling of being in the presence of a filmmaker whom I don't entirely trust - not in the sense that I feel the filmmaker is not up to the snuff of delivering a good fright, but in the sense that said filmmaker might just be a little...off; perhaps eccentric, or even insane, to have delivered such a god damned strange, indecipherable, and flat-out bizarre little picture like the one we'll be celebrating today. To watch

Tourist Trap is to wonder if the film had been accidentally made by an escapee from an insane asylum after he had held a mini-studio hostage so that his film may be realized. And when I insinuate the filmmaker was approaching this in as unconventional manner as possible, I don't allude to such high-brow works of art like E. Elias Merhige's

Begotten or even

Buñuel & Dalí's Un Chien Andalou, which are artistic to the extreme of defying convention. No, Tourist Trap is a different kind of insane - one that sports a straight-forward concept that became rather go-to in the late '70s and early 80s thanks to The Texas Chain Saw Massacre: a group of kids getting lost in an unknown territory and falling victim one by one to a madman. On its surface, one would assume that's all it would seem to entail. But oh, how wrong one would be to assume such a thing. (That filmmaker, by the way, is David Schmoeller: read my interview with him

here.)

Have you ever heard the expression "a mystery wrapped in a riddle wrapped in an enigma?"

Tourist Trap is that movie, in spades, but with mannequins. It, truly, is the most bizarre film I’ve ever seen - one that at some points is deeply unsettling, and at others completely ridiculous, whimsical, and odd. It’s almost as if two directors, whose styles completely contradicted each other, directed different portions. Picture an unhappy studio executive screening the latest film from David Lynch, then picking up a phone and requesting an immediate meeting with the guys who made

Airplane.

The beginning of Tourist Trap introduces us to a group of young teens as they are temporarily stalled by a flat tire on their way cross-country. One of the unlucky boys, who is the spitting image of the late Steve Irwin but sans accent, rolls the flat to the nearest service station for help. Upon getting there, the boy is haunted by weird, ethereal, slightly erotic moaning emanating from an unseen source. The boy locates the source: a blanket-covered woman lying on a cot in the back of the service station. The boy approaches gingerly, asking the woman if she needs help. Suddenly, she springs forward, laughing in vicious glee, revealing herself to be...a mannequin.

Your mind barely has time to process what appears to be the film's first major development before all hell breaks loose in this little room. The mannequin continues to laugh, its plastic jaw clomping wildly in glee. The boy, understandably freaked, tries to escape the room, but windows close and lock themselves as doors slam themselves shut.

Another mannequin, this one headless, smashes through the outside window. The boy is then assaulted by yet another mannequin, bursting forth from the closet and laughing more creepily than the previous dummy. As the boy backs up in fear, he kicks a small mannequin head that lies on the ground. He looks on in fear as the head slowly turns and opens its mouth wide.

And your reviewer is utterly disturbed.

The room begins going insane as cabinets open and close and objects are mysteriously hurled at the boy as he tries to escape, and all during this fiasco the mannequins continue to laugh.

My God, is this what it's like inside Gary Busey’s head?

A metal pipe is suddenly hurled through the boy, killing him instantly, and the commotion comes to an end. We then pan around the room, taking in the sudden serenity, as if the mannequin-screaming, object-hurtling, window-and-door-slamming shitstorm of a fucked up Quaalude hallucination never took place.

This is certainly not a case of establishing something insane for the purposes of securing a massively crazy opener, but failing to live up to that insanity for the remainder of the film. Rather, Tourist Trap wants to hit the ground running. It wastes no time in easing the viewer into the insanity that is soon to unfurl. "We've only got 90 minutes here, people," the film is saying, "so strap in for the worst nightmare you've ever had while wide awake."

The dead boy's friends, among them Molly (Jocelyn Jones), the "final girl," come looking for him, and this is when they meet Mr. Slausen (Chuck Connors), owner of Slausen’s Lost Oasis, who approaches them with a large shotgun and cowboy hat. Soft guitar music plays as Slausen lays down his airing of grievances he has with the local town bureaucrats as the girls, having previously stripped down and leaped into a nearby watering hole and are now naked as they day they were born, cover their dirty pillows and stare at him with a mixture of fear and confusion.

Despite the fact that he is clearly the last person anyone with half-a-brain would want to be around, they accept his offer of a lift back to his house under the guise of getting some tools to help fix their car. But don't worry, these kids aren't going anywhere. Both the audience and Mr. Slausen want to see these kids get haunted and slaughtered by sighing mannequins. And boy, will they.

To attempt to explain or make sense of what's soon to unfold is a fool's errand. To date, I have seen

Tourist Trap three times, and I am completely unable to decipher anything that occurs. A rather simple-minded premise about mannequins with a life of their own soon morphs into a story featuring quirky and potentially dangerous twin brothers, split personalities, telekinesis, necromancy(?), and even heartbreak.

All of this, on the surface, feels easy to mock, and I fully admit the first draft of this column was written to be included as the newest edition to

Shitty Flicks. But my latest viewing of this flick confirmed I could not in good conscience do so. Low brow concept it may have been, and populated with not-so-great teen actors as was often the case for low-budget horror, writer/director David Schmoeller knew exactly what he was doing behind the camera. Without hyperbole, every single solitary shot of a mannequin, or doll, or masked madman, is eerie, or disturbing, even deeply unsettling. Because nothing makes sense. And no explanations are provided. If you're looking for the James Bond villain-esque explanation at the end where the antagonist lays it all out on the table - "here's how I bring the mannequins to life / here's how I learned to move objects with my mind / here is how I resurrect the dead" - forget it. You're barking up the wrong tree here, and you're way way way in the wrong film. I've long said that gaps in logic can be detrimental to a screenplay unless you are in a filmmaker's such capable hands that you not only forgive those gaps, but actually respect them and allow them to enhance your reaction to the story. It gets to be that you

want to ignore these gaps, because to do otherwise would result in over-thinking and ruining the experience for yourself.

Each insane development occurs with no for warning, because Schmoeller wants you to feel just as broad-sided as his characters. "Wait a minute, since when can this guy move shit with his mind?", etc. He wants every new occurrence of supernatural territory to slap you across the face. He wants you to feel uneven and on edge, honestly believing anything could happen at any moment. At one point someone could have opened their chest to reveal they were a robot the entire time and it would have felt right at home. (Not to mention something like that kinda-sorta happens.)

Schmoeller is also wise to exploit the hordes of mannequins found everywhere in Slausen's Lost Oasis to immense satisfaction and disturbance. At one point the killer is chasing one of our victims and holds out, at arm's length, a severed mannequin's head.

“See my friend?” the killer grumbles, as the mouth on the mannequin head opens widely and screams.

At this point we have seen enough insanity and unexplained activity that we know this is not a simple case of ventriloquism: This head is somehow alive, and it's screaming at our victim like it is being brutally murdered. This is later confirmed when the killer heaves the screaming head at her as she turns and flees. The head, landing on the ground in front of her, promptly turns by itself and yells at her again.

Adding to this insanity are the occasional bouts of humor. Not unintentional humor, mind you, but honest-to-gosh scenes in which Schmoeller forgot he was making a haunted mannequin, masked-killer movie and was perhaps instead directing a vaudevillian stage play featuring Abbot and Costello.

That decision results in the following scene in which our killer enters a room wearing a mask and sits down next to a mannequin. For no reason whatsoever, after the killer places a bowl of soup in front of the slumped-over mannequin, the dummy suddenly springs to life:

Killer: Eat your soup. It’s nice and hot.

Mannequin: Let’s eat.

Killer: That’s what I said, let’s eat. Is it good?

Mannequin: Yes, it’s very good.

Killer: Want some crackers?

Mannequin: I’d like some more crackers, please.

Killer: That’s what I said.

Mannequin: Yes, the crackers are very good.

Killer: Aren’t da crackas good??

The mannequin’s head falls off directly into the soup, ruining the rest of the date. All of this in the midst of teens being killed and transformed into mannequin parts, one by one. All of this while mannequin heads scream and move on their own, while objects fly across the room without having been touched, while people whom we thought were perfectly real and alive are torn apart limb-from-limb, revealing they were actually mannequins.

Also adding to this insanity is the completely wacko score by Pino Donaggio, perhaps most famous for having scored the majority of Brian DePalma's earlier films like

Carrie and

Dressed to Kill. Much like

Tourist Trap itself, the score alternates between chilling, with stabbing strings, and goofy, with clumsy xylophone hits. It's an awkward pastiche that at some points is trying to drive you mad with fear, but at others is trying to convince you you're in the presence of someone whimsical and eccentric and you should be having a really amusing fucking time.

The last shot shows our lone survivor driving down the street with mannequin versions of all her friends filling out the car that now suddenly works, as Pino Donaggios’s score assaults your every sense, slamming home the fact that, yes, what you just experienced was real, and no, you will never forget it.

Tourist Trap was unofficially remade in 2005 and dubbed

House of Wax, as that was the title Warner Bros. happened to own. And yes, while it includes a killer who turned his victims into wax dummies, the similarities end there. But it would go onto lift, from

Tourist Trap, the killer-brothers concept, the broken-down-car concept, the weirdo-attraction-in-the-middle-of-nowhere concept, and hordes of mannequins/dummies particularly placed and posed to give off the illusion of being real people.

David Schmoeller would go on to direct more straight-forward genre fare like

Puppet Master and episodes of "

Silk Stalkings," but

Tourist Trap will always be remembered as the movie that made people say: “That was fucking weird. I don’t feel good…”

God bless you, David Schmoeller.

God bless you, Tourist Trap.

God bless us everyone.

I’m gonna go take a shower and hide under a blanket, because I feel really uncomfortable.