When the trailer for John Wick was released, no one expected much. It didn’t particularly sell that film in the way it deserved to be sold, focusing more on the dog and goofy carnage rather than the exceptional choreography and the clever world building. I was in from the start because Keanu—I’ll watch him in anything (I even somehow sat through Knock Knock)—but I wasn’t expecting the well made, sincere, and very fun film that John Wick was.

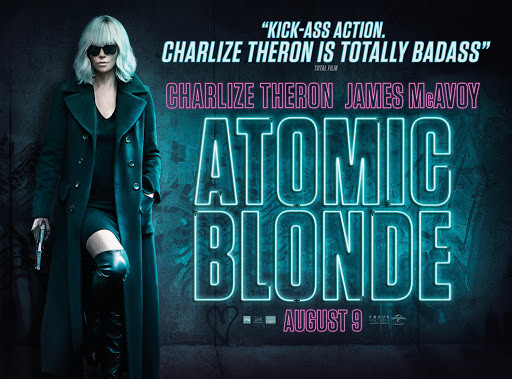

Its two directors, former stunt men Chad Stahelski and David Leitch, soon split off in diverging paths: Stahelski committed to John Wick: Chapter 2 and Leitch to Atomic Blonde. If there was ever any doubt that one director was the secret weapon of John Wick's success, John Wick: Chapter 2 was step one in dispelling that notion. Atomic Blonde is step two.

Atomic Blonde has been meticulously designed and Leitch proves he can absolutely hold his own as a director working solo. Despite how it was marketed, it’s not the female response to John Wick, instead taking its page from paranoid spy thrillers of the ‘70s but reinvented with the neon-loving flamboyance of Nicolas Winding Refn. David Leitch directing Confessions of a Dangerous Mind instead of George Clooney offers a pretty broad but helpful means of warning the audience what kind of film they’ll be getting. Don’t get me wrong, Atomic Blonde does have a handful of extremely impressive action scenes on display—one in particular is presented in the form of a minutes-long unbroken take and rivals anything seen in either John Wick flick—but the film is more interested in cloak-and-dagger espionage, double- and triple-crosses, political Cold War unrest, and hewing at least a little closer to reality by presenting Lorraine Broughton as a bad-ass but entirely human and fallible character. Even after rolling down a hundred concrete steps, John Wick can get up and have a drink. Broughton doesn’t bounce back so quick—her body, which Theron isn’t shy about showing off, is her personal roadmap of pain.

And speaking of Broughton, between the obvious Mad Max: Fury Road and now Atomic Blonde, Charlize Theron is having a grand old time kicking everyone’s asses. On top of looking good while she’s doing it, she excels at it. She looks well suited to this kind of material, and even when she engages in the most painful of action set pieces, it’s evident she’s having the most fun out of everyone. Atomic Blonde tries to strike a similar tone to the Craig era of the Bond franchise by injecting a cheeky sense of fun into an otherwise serious story, but where Bond’s generally light tone was more conducive to that kind of balancing act, Atomic Blonde can be very dark at times, and also violent, even grisly, so when the film opens with a John Wick-ish chase scene set to an iteration of Blue Monday, but later on a minor character is violently beaten in the face with a skateboard, Atomic Blonde can seem very tonally confused. Despite that, it’s extremely well made, and all the actors commit, obviously including Theron. It’s still undecided if Atomic Blonde, based on the graphic novel Atomic Blonde: The Coldest City by Antony Johnston, will birth a second franchise for her, but it’s certainly worthy of one.