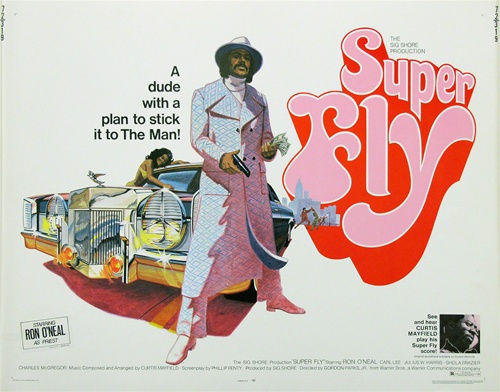

In the pantheon of the Blaxploitation movement, Super Fly was considered a top-tier title, boasting the most recognition and all around favorable reputation second only to Shaft, which was rebooted once in the early 2000s and again last year. A remake, Superfly, was released in 2018, produced by Joe Hollywood himself Joel Silver, and featuring a cast of actors who, outside of Michael Kenneth Williams, I’ve never heard of.

Super Fly follows that age-old tale of a criminal/hero, in this case the bad-assedly named Youngblood Priest (Ron O’Neal), as someone tired of the game and looking to secure one last big hit before retiring from his life of crime for good. Of course, such things are never so simple.

Super Fly’s plot isn’t wholly engaging, and its effort to look raw, gritty, and realistic leads to scenes going on too long in an effort to capture their authenticity. (In fact, a real New York City pimp who lent the filmmakers his “tricked out hog” to use on screen eventually made his way into a scene playing…a pimp. His unpolished acting skills are prevalent, but, again, it lends to the authenticity.) And as far as the grit and rawness, one of the first scenes sees Priest chasing a would-be robber all the way back to the robber’s apartment where a woman and several small children cower in a corner on top of a mattress sat on the floor. Priest retrieves his cash and brutally kicks the man several times in the stomach, causing him to vomit — all the while, the chipped, peeling paint and dingy gray interiors of the apartment imbue that kind of New York nastiness that permeated much of 1970s cinema.

Super Fly’s plot isn’t wholly engaging, and its effort to look raw, gritty, and realistic leads to scenes going on too long in an effort to capture their authenticity. (In fact, a real New York City pimp who lent the filmmakers his “tricked out hog” to use on screen eventually made his way into a scene playing…a pimp. His unpolished acting skills are prevalent, but, again, it lends to the authenticity.) And as far as the grit and rawness, one of the first scenes sees Priest chasing a would-be robber all the way back to the robber’s apartment where a woman and several small children cower in a corner on top of a mattress sat on the floor. Priest retrieves his cash and brutally kicks the man several times in the stomach, causing him to vomit — all the while, the chipped, peeling paint and dingy gray interiors of the apartment imbue that kind of New York nastiness that permeated much of 1970s cinema.

There’s also an emphasis on showcasing New York black culture with the appearance of Curtis Mayfield in a small, smoky club where our characters gather at one point. Long, unbroken takes of Mayfield performing one of his most well-known songs, “Pusher Man,” make up a large portion of the scene, with the entire club — including our hero — rapt with attention. In fact, “Pusher Man” is such a dominant presence in Super Fly that it’s used three different times.

Ron O’Neal is a striking looking actor, and his mixed heritage lends him an atypical look that was usually bestowed upon most of the male Blaxploitation characters of that era. It’s easy to dismiss his performance at first as uninspired and flat, but as time goes on you begin to see that O’Neal is manufacturing an almost untouchable mythical figure who knows only one emotion: fury. Cross him and he’ll make you pay, and in the scenes where he’s laying to waste a character who needs a furious verbal reprimand, he absolutely commands the screen.

Super Fly has rightfully earned its place in Blaxploitation history; it’s one of the few from the sub-genre that was able to transition from the screen and permeate pop culture, inspiring a long line of actors, hip-hop artists, and even halfhearted, big-budget reboots.

No comments:

Post a Comment