Apr 5, 2024

Jan 3, 2022

HALLOWEEN: H2NO

I don't know why, but I've had the Halloween series on the brain recently. Perhaps it's because of the impending video release of Halloween Kills, or perhaps it's because I always do.

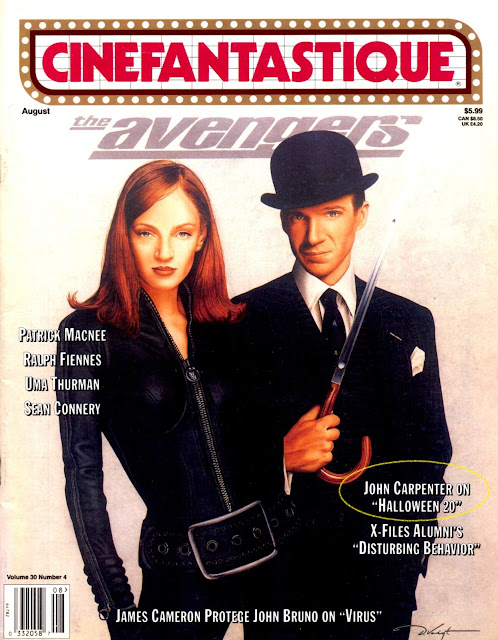

After digging around the Internet Archive (best site ever), I found a treasure trove: a digital archive of Cinefantastique's thirty-plus-year run, and with it some coverage of Halloween: H20, specifically an interview with John Carpenter regarding his earliest flirtations with directing the film before ultimately passing. I was but a wee tyke when Halloween: H20 was released and it remains, to this day, the most excited I'd ever been for an upcoming movie. Because the Internet was still fairly new at the consumer level (my family was always behind the technological eight ball, so we weren't yet surfing on the world wide web), I'd made it a habit of prowling newsstands for magazine coverage in the off-chance I'd find a publication that had written about it in hopes of learning everything I could about this exciting new sequel. It was during this time when I discovered the existence of mags like Fangoria, Rue Morgue, Cinefantastique, and others that didn't just cover genre cinema but were actually dedicated to genre cinema. I was blown away and I snapped up every cover baring The Shape's mask, which is a tradition I dusted off for 2018's Halloween and its underwhelming sequel.

I actually remember seeing this specific issue of Cinefantastique at my friendly neighborhood comic book shop (shout-out to A Time Lost and Found) back in 1998, over twenty years ago (what the fuck holy shit what's happening) and it was pretty wild to see it again.

Oct 20, 2021

HALLOWEEN KILLS (2021)

It’s been a very long time since

I’ve encountered a horror movie as polarizing as Halloween Kills. I'd have to go back more than a decade

to, ironically, Rob Zombie’s Halloween,

or the Platinum Dunes remake of Friday

the 13th. Far be it from me to think I can cover anything that’s not yet been covered in reviews across the internet, from

mainstream critics to genre-friendly websites to legions of social media

posters. I have seen ten/tens, zero/tens, and everything in between. One

commenter stated that the 1978 original and Halloween Kills are the only Halloween

films they’ve ever liked, and they’d much sooner watch this newest sequel than

the original. Meanwhile, on the opposite end of the spectrum, Halloween Kills has been hugely

maligned for a whole host of reasons, most of them fair—depending on what

“fair” means to you. Because of this disparity, reviewing Halloween Kills feels like screaming into the void alongside

everyone else, like sitting in a room and arguing among friends about which

local greasy spoon makes the best pizza—because everyone has an idea of what

they want, and that idea can be radically different from person to person.

The problem with the Halloween series, or really any ongoing series that had a legitimately good first entry and later devolved into broadly distilled, sensationalized versions of the same concept, is that audiences become split as to what they want. The first movie creates the mold and the rules, but every sequel, by design, has to do something new, and through their very nature, they become sillier and sillier parodies of their own idea. So, who decides what a new entry in an established franchise should be like? Should every new entry try to be "good," or should it merely carry the torch and keep the franchise alive, just like all its lower-reaching sequels? The first Halloween is a critically lavished film that even Roger Ebert once referred to as a classic, so each time a sequel is made, a portion of the audience hopes to see something that lives up to that legacy—something classy with an emphasis on suspense over gore. Most of the Halloween sequels aren’t good movies, though they are fun in their own way (I'll always defend Halloween 4 as being a good one, though maybe I’m alone in that), so when you've got two halves of the audience vying for polar opposite experiences, what happens as a result? Well, those schools of thought collide in a violent crash, and because we're living in 2021 AR (After Reason), a time during which everyone is angry about everything all the time, even something as innocuous as a movie can cause blood-raging fights.

Once you see Halloween Kills—or any movie, really—you henceforth belong to “the

audience.” We all become one mass, just one more community we now share, even

though we’re all looking to the movie to satisfy our own personal desires with

little regard to what the person in the next seat may want. Those

desires can be polar opposites, but they can also, and often, be granular, as everyone has already established their own barometer for satisfaction. What’s

that mean? At the end of the day, there’s only one version of a movie (well,

for the most part—Halloween: The Curse

of Michael Myers is somewhere saying, “Hold my four different cuts”), which

means it’s only going to entertain a certain fraction of the

audience—especially one as bloodthirsty as Halloween

fanfolks. In an effort to entertain both schools of thought, I’m approaching

this too-long review in a different way. The first half will be written by

someone who wanted Halloween Kills

to be legitimately good in the same way as the original and the 2018 reboot. The second half will be written by the part of me that

acknowledges Halloween Kills is the eleventh movie to feature Michael Myers

wandering around Haddonfield and killing townspeople in all kinds of ways, and as such, didn’t expect much beyond some senseless violence and a

reasonably engaging story. Depending on what you want from Halloween

Kills, pick your poison and read on. (Spoilers everywhere.)

Take 1: “I Wanted A Good Movie”

Prior to its arrival in theaters

to both huge box office and critical acclaim, 2018’s Halloween seemed like a real longshot. In the years preceding, Rob

Zombie had killed the series dead with his experimental nonsense, and this was

after 2002’s dismal Halloween:

Resurrection had already killed

the series along with its leading final lady. (If next year’s Halloween Ends kills off Laurie Strode,

that will be the third time her character

has died in this goofy series—pretty impressive.) There was understandable

excitement when it was announced that John Carpenter would be serving as

spiritual consiglieri to the reboot after having spent the last 35 years away

from the series, as the closest he’d come in that time was quitting Halloween: H20 in the earliest days of pre-production. Then came the announcement of Jamie Lee Curtis’s return as the

embattled Laurie Strode and the mood went from “oh?” to “oh!” Enthusiasm for

the project was palpable. Then came the announcement that the guys who had done

Your Highness, David Gordon

Green and Danny McBride, would be handling the project, and the Internet had no

idea what to think. I sure didn’t. These guys

were going to resurrect a series that hadn’t been worth a damn

since 1998? (Midnight Mass’s

Mike Flanagan also pitched his own version for a reboot, most of which was repurposed

for Hush, his Netflix Original home

invasion flick. I'd still love to see what Flanagan's Halloween would've been like. Maybe someday...during franchise retcon # 3.)

Despite everyone’s usual

cynicism, Gordon Green and McBride (and poor Jeff Fradley, the film's third co-writer who is seldom mentioned), under the watchful eye of John Carpenter, managed

to deliver one of the best sequels in the series, with Carpenter going on

record as saying it was better than his original. With the dream team having fairly earned the accolades for their approach, there was no reason to believe Halloween Kills wouldn’t be at least comparably good, or at the very

least wouldn’t squander the goodwill

established by their first go-round.

The curse of the sequel strikes

again.

The “good” news is Halloween Kills isn’t the worst sequel

in the series, regardless of the timeline you’re sticking with—I don’t think

we could ever plumb those kinds of depths ever again—but based on the pedigree

involved, the poor execution of good ideas, and the good execution of a less intellectual and more visceral experience, that leaves Halloween Kills in a kind of cinematic

no man’s land where it’s hard to choose one side or the other, and that’s

worse. Halloween: Resurrection, for

instance, is a piece of shit I’ll never watch again; though unfortunate, there’s

no conflict there and I’m at peace with its place in the Halloween hierarchy. Halloween

Kills has a lot to offer, and parts of it are terrific, but its best parts don’t push the narrative

forward in any meaningful way, which is its biggest detriment. If your movie

doesn’t have a point, then fuck—what are we doing here? Though Halloween Kills definitely tries, and it has ideas either brand new

or fleshed out from previous sequels (the vigilante aspect from Halloween 4, for example), what

we’re left with feels unfinished, overwrought, and aimless; really, it feels more like an

extended opening act for Halloween Ends.

It’s the holding pattern of horror sequels—the palate cleanser in between

courses—and that sucks.

Though Halloween Kills continues exploring the concept of trauma as established during its predecessor, this time the series expands beyond Laurie Strode and her family and looks at how the other citizens of Haddonfield are still emotionally reeling from the night he came home and how that trauma manifests…which is with revenge. Right out of the gate, this newborn series seems to be transitioning from philosophical and intimate nuance to primal, in-the-streets chaos. Halloween Kills is a malfunctioning carnival ride wrenching loose from its hydraulics and shooting off a nonstop torrent of sparks in the form of very wet and crunchy violence with a plot inspired by the third act of 1931’s Frankenstein (only Michael Myers deserves it). In the conceptual sense, it doesn't stray too far from what Gordon Green et al. established in 2018, but it does choose to do something that feels quite wrong for a Curtis-having Halloween movie: completely remove her from the equation, making this latest sequel feel perfunctory and incomplete. Halloween Kills is the sixth Halloween film to feature Curtis' Laurie Strode, but the first in which she never shares a single scene with her masked nemesis. Of course, this was by design, as the filmmakers wanted this entry to be about the rest of Haddonfield ("One of their numbers was butchered and this is the wake," Loomis says in Halloween 2 while Haddonfield townspeople are vandalizing the abandoned Myers house), but also because the filmmakers would really be straining credibility in having Laurie walk away unscathed after so many encounters, especially with a gaping wound in her belly. While all of that is perfectly reasonable, at the same time, it makes the experience of Halloween Kills feel incidental—like it's not actually a Halloween sequel, but more like some random external adventure happening in a Halloween shared universe. If it’s Halloween, Laurie and Michael have to do battle—that’s, like, a rule. If you’re playing in the canon sandbox established in 1978, then you’ve broken that rule—just one among many. That’s like having James Bond call the police on the main supervillain instead of taking the guy out himself.

My biggest gripe with Halloween Kills is its poor treatment of the legacy actors and characters being glimpsed for the first time in forty-three years. Featured most prominently is Tommy Doyle, the young boy Laurie was babysitting Halloween night of 1978, this time played by Anthony Michael Hall. (Conversations were had about having Paul Rudd come back to play the part after having done so in the now de-canonized Halloween: The Curse of Michael Myers, and at first it was disappointing it didn’t work out, but seeing what the movie had turned Tommy into, not even my perpetual love for the Ruddster is enough to convince me he could’ve played the part as required.) Alongside Tommy are Lindsey Wallace (a surprisingly terrific Kyle Richards), Marion Chambers (Nancy Stephens), and Lonnie Elam (the wonderful Robert Longstreet of The Haunting of Hill House) while retired sheriff Leigh Brackett (Charles Cyphers) is working a security shift at Haddonfield Memorial. As a lifelong series fan, of course it was incredible to see those characters and/or actors return to the series...but also a damn shame to see how wasted most of them are. How do you have Laurie Strode and Leigh Brackett under the same hospital roof and not allow them to share a single scene together, perhaps one in which they collectively mourn over the slain Annie, her friend and his daughter? (Nancy Loomis appears in archive footage from Halloween and, oddly, Halloween 2, which technically doesn't exist in this new timeline, but which is still used in an appropriate and unobtrusive way.) Though the yearly Halloween-night binge drink was a clever way to group all those 1978 massacre survivors together, why not give them each just a single moment to come off like human beings with a shared history? Though I value their inclusion, their presence smacks of vapid “look, see?” fan service in hopes we’ll get lost in dreamy nostalgia and not notice how superficial their appearances are—not to mention that killing four out of the five characters seems a little sadistic, with three out of the four being killed in dismissive ways, as if their place in the series never meant anything. Brackett ranks a blink-and-miss-it face slash; Marion, who dies for the second time in this series, has the honor of going out looking like a fumbling idiot; and poor Lonnie doesn’t even get an on-screen death. Tommy is the only legacy character to get a ceremonial end, and even that felt wrong.

And all during this, bit players from Halloween '18 who were never even given names return in expanded roles, only so Halloween Kills can snuff out even more recognizable people, and with great violence. (I cringed at that "oops!" self-inflicted gunshot wound. Is this Halloween Kills or Abbott & Costello Meet The Shape?) While it makes sense to reuse characters you've already created instead of introducing new ones, it seems really strange that these characters, who haven't had their own face-to-face encounter with Michael Myers and who only learned about him for the first time Halloween night of 2018, would so immediately want to throw hands alongside these legacy characters who've lost loved ones, or nearly died at Myers' hands, or spent the last forty years navigating their own traumas. I'm tempted to think it's meant to be some kind of commentary on tribalism and the deadly consequences of in-the-bubble information loops, but I might be giving something called Halloween Kills too much credit.

Though Halloween Kills jumps from location to location and timeline to timeline, with something heavy going on almost all the time, it never feels like anything is happening; it’s desperate to do so many things that it eventually collapses under its own heavy load. It wants to be “about” something but executes that aboutness with the subtlety of a sledgehammer. It wants to pretend the reveal about The Shape being supernatural in nature is some kind of gigantic, world-stopping revelation...until your most basic fan remembers that Dr. Loomis shot him in the chest six times in 1978 and "he just got up and walked away," the discovery of which didn't surprise Loomis in the least. It wants to establish the origin story of Frank Hawkins (Will Patton) by trying to convince the audience that his past with The Shape is just as intertwined and significant as Laurie's own, but it simply can't stand up to the forty-year head start she has, nor with Curtis's consistent presence in the series, even if most of her sequels have been retconned out of this current continuity—along with the carelessly established motivation for Hawkins' character hinging on his forty-year regret for not shooting The Shape in the brain when he had the chance...even though it's been solidly established that probably wouldn't have killed him anyway. Even Andi Matichak’s presence as Allyson is wasted on the vigilante angle, which not only feels wrong for her character but feels more like the movie is babysitting her for the time being in lieu of offering her something more substantial to do. More than anything, and maybe years down the line he'll confirm this, Halloween Kills feels like the kind of senseless, garish sequel Carpenter would've hated, had it been attached to the franchise's first timeline that, after a while, he had nothing to do with.

Take 2: “I Wanted A Fun Movie”

Halloween Kills is a fucking blast. With a body count of fortyish people, there’s a violent and brutal death something like every three minutes. Though Gordon Green returns as director, and still channeling Carpenter by recreating a few shots from the original, this time he's embracing his inner Argento. The gallons of blood used during production must be somewhere in the thousands. Holy smokes, is this thing Italian? Between the bloodletting and the corny dialogue, it must be.

Halloween Kills also presents Michael Myers

at his most brutal, vicious, mean-spirited, and utterly unremorseful. His

fire-scorched mask gives him the Jaws 2

treatment, which is appropriate because Halloween Kills has turned him into an unstoppable killer shark. (Yep,

I just quoted Busta Rhymes from Halloween:

Resurrection. Haw haw.) James Jude Courtney, with a little assistance from Airon Armstrong for the '78 sequence, returns for another round of Haddonfield mayhem and strikes an even more imposing figure than his last appearance. The Shape of 2018 was methodical but physically capable; here, he's embraced his full-on Kane-Hodder-as-Jason-Voorhees, dispatching his victims in ways we've yet to see in this series. Sure, he does his playful cat-and-mouse thing by hiding in dark corners and behind closet doors, but really, who gives a shit? Why bother? The Shape of Halloween Kills is going for quantity over quality. He could've knocked on the door dressed as the pizza dude or popped out of a sugar bowl to lop off someone's head and the audience would've barely reacted. And that's because, as Halloween Kills ably communicates, the death of any character we see on screen is inevitable. There's no hope for anyone—not even Stewie from Mad TV ("Look what I can do!"). And boy, the movie wastes no time in getting to those deaths: the opening massacre of the first responders to Laurie's farmhouse inferno is awe-inspiring—and the closest we've gotten to seeing The Shape kill someone with a chainsaw.

Before the first

retcon in 1998 with Halloween: H20,

the Halloween series had been that

random horror property Jamie Lee Curtis appeared in for just a couple

movies before saying farewell and moving onto bigger studio fare, in the same

way lots of actors had done their one random appearance in famous slasher series:

Kevin Bacon in Friday the 13th,

Johnny Depp in A Nightmare on Elm Street,

even Jennifer Aniston in Leprechaun.

Though their involvement in said projects waver from pride to embarrassment, none of them really talk about them unless prompted, and they certainly never went back to that

well for another go-round. (Sure, most of them died in their respective movies, but since when has that ever stopped Hollywood?) When Jamie Lee Curtis returned to the series for the first time in 1998,

it felt like an event because it was an

event, and though her presence in a Halloween

film doesn’t guarantee it’s going to be good, it still feels right. And seeing her stick with this

series forty years after the original movie is special. At this point, Halloween belongs to her and John

Carpenter (and the every-day-missed Debra Hill), and here they are, all these years later, playing make-believe together like a bunch of kids once

again—this time with filmmakers who grew up on the very movies they're now putting their own stamp on. Output aside, what a nice thing.

Speaking of, Carpenter, son Cody, and Daniel Davies return to score, offering another sinister, kick-ass musical landscape. Themes from both Halloween eras are present and accounted for, along with a whole host of new material to properly shadow this new take on Halloween lore. Their score even acknowledges the angry mob angle, for the first time ever adding a chorus of voices to the legendary Halloween theme, which plays over the opening credits that feature not just one illuminated jack-o-lantern, but a dozen—each one growing more intense with flames as they flow past.

What does it all mean?

Haddonfield

citizens are mad as hell and they’re not gonna take it anymore.

The 1978 timeline stuff, which sees Michael's detainment by Haddonfield police, including young Frank Hawkins (Thomas Mann) and his partner, Pete McCabe (the always enjoyable Jim Cummings, actor/director of The Wolf of Snow Hollow), works damn well, and is probably the best material in the whole movie. The loyal recreation of the Myers house is terrific, as is the mask, which is the closest this series has gotten to faithfully depicting those two holy totems. Evidently some fans have been blasting the “all CGI Loomis” that was inserted into this sequence, somehow not recognizing him to be a real, living, non-CGI human being (Tom Jones Jr.). Has CGI really gotten that good? I guess I haven’t noticed. Though the actor’s appearance is uncannily spot on, and overdubbed by the previous movie’s convincing Loomis soundalike, this new version of Loomis would've been better left in a blurry background, similar to how Michael’s maskless face had been obscured throughout the first two movies of this new trilogy. Still, seeing his trench-coated form standing at the Myers house threshold as the camera cranes back across the front yard, revealing a motionless Michael flanked by police—in a shot that mimics the original's opening scene where six-year-old Michael has his clown mask ripped off by his father—well, it’s the stuff of legitimate chills, and Carpenter and co’s revisitation of the same theme used for that scene but now gussied up with disconcerting overlays is probably the movie's greatest moment. (But where are the six bullets Michael had just taken to the chest?)

The fake ending, in which the

Haddonfield mob finally appears to get the best of their boogeyman with a

bad-ass beatdown, only for Michael to gain the unsurprising upper hand and give

them all a little what-for, is terrific, exciting, and that offers the audience some manipulative catharsis—but in a

strange way, also offers the audience a little hope. “He’s turned us all into

monsters,” Brackett says following the hospital mob’s near-lynching of an

innocent man, which may be the moral of Halloween

Kills: no matter how vicious Haddonfield’s people become—and really,

they're us; we’re that mob—we can

never be as evil, black, and unfeeling as The Shape. In this scary day and age,

I’ll take it.

Halloween Kills chooses to end with a shocker of a moment—the death

of Karen (Judy Greer), which doesn’t just play out in Judith Myers’s old bedroom

in the fabulously restored Myers house, but is even executed in the same way as

Judith’s death in 1963: thrashing hands, obscured points of view—no glimpses of actual

violent penetration, but still uncomfortable to witness. I’m surprised they

didn’t pop in the ol’ eye-hole stencil to give us a look through Michael’s

mask. A move like this is pretty ballsy, and is frankly the only important thing that happens in the entire movie, because it now means Laurie Strode,

technically, has failed—that the years and years she spent training her

daughter to survive against the evil in the world, which did

permanent damage to their relationship and shaped them both into broken people,

didn’t mean a damn thing in the end. And with the recent revelation that Halloween Ends is going to be set four

years after the events of Halloween '18 and Halloween Kills, that’s

plenty of time for Laurie to grow even crazier. And for the series to grow

crazier, too.

If I had to break down this entire manifesto into one sentence, it would be this: Halloween Kills is a good slasher movie, but a bad movie in general…and yet I still kinda liked it. In spite of its hideous dialogue ("Evil dies tonight!") and aimless plot, I've actually been thinking about it off-and-on since having watched it, which is more than I can say about some other "better" flicks I've caught recently. No matter on what side of the fence you land, you can’t deny Halloween Kills offers a new flavor to the unkillable series, made with a certain operatic and violent flamboyance that’s difficult to shake. I don’t know why, but I have this odd feeling, in years to come, it’s going to enjoy a ground-up reevaluation—either by the first-round audiences left underwhelmed during its preliminary release, or by the next generation of viewers who find it, similar to how the wonky Halloween III: Season of the Witch has been recently embraced after so many years of dismissal. Love it or hate it, Halloween Kills may very well have staying power, and I’ll be morbidly interested to see how it holds up in five, ten, or forty years from now.

Oct 17, 2021

HALLOWEEN 4: THE RETURN OF MICHAEL MYERS — FULL NBC BROADCAST, 1989

Following my previous fan edit "broadcast" of George A. Romero's Dawn of the Dead, I decided to do something similar in honor of the spooky season. Much like Dawn of the Dead, some of the Halloween sequels never enjoyed network broadcasts in their heyday. To date, the most high profile broadcast of a Halloween movie was the 1978 original, which premiered on NBC in 1981 the same weekend that Halloween II opened in theaters. (This was the edit that's become known as the "television version," which includes three new sequences shot by Carpenter using Halloween II's crew to help pad the running time to fit within a two-hour time slot.) While Halloween II and Halloween III: Season of the Witch did air on television in the mid-1980s, both aired on affiliate channels with pre-existing licensing agreements with Universal Studios, who owned both sequels (and who also own the current Halloween timeline, comprising 2018's reboot and this year's disappointing Halloween Kills). Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers and Halloween 5: The Revenge of Michael Myers were made independently and never aired on network television or even on local syndicates outside of premium cable channels. Because of this, and being someone who owns a copy of every known broadcast of a Halloween movie, the lack of Halloween 4 always felt...wrong.

Decades spent watching the Halloween series has allowed me to embrace a possibly controversial truth: after Carpenter's original, Halloween 4 is my favorite of the series by a lot (not counting the Shapeless Halloween III, which is nearly tied). There's a variety of reasoning behind this: one, it's well made and appears genuinely respectful of the source material; two, because if you've stuck with the series through thick and thin, then you know how off-the-rails the series went with each timeline, making Halloween 4 look better and better by comparison; and three, and this is the biggest one—nostalgia. While the series' original run that began with the very first and ended with 1998's Halloween: H20 all lovingly exists under that warm and comforting nostalgia blanket, there's something about Halloween 4 that really hits me in the feels. All of that is what led me not just to fan-editing a network broadcast that never actually happened, but it had direct influence on how I designed the edit.

With my Dawn of the Dead edit, I kept all commercials confined to a late-70s and very-early-80s aesthetic, with most of the commercials being in-jokes based on Dawn of the Dead's content. (There's a bonafide commercial for Monroeville Mall—that kinda thing.) With Halloween 4, I kept the era appropriate to 1989 or close to it, but I also I made it a full-on nostalgia boner for everything Halloween season—commercials for costumes and makeup, all kinds of weird and spooky 900 numbers geared towards children (including Freddy Krueger's infamous hotline), and of course, TV spots for notable or infamous horror flicks released that year. It was designed for background play during your Halloween party, or to sit down and watch in its entirety—the hope is to stoke your own fires of nostalgia as you get lost in this more and more celebrated decade.

Like Dawn of the Dead, this edit of Halloween 4 has been censored for content to adhere to network standards, but luckily, unlike Dawn of the Dead, Halloween 4 didn't have that much content to remove because it was a pretty tame and chaste sequel compared to what would come in the franchise's future, so this edit isn't very jarring. It also felt right using NBC as the hosting network, as it had aired the premiere of the original almost a decade previous to this one—it felt like the series had gone home. I hope you enjoy this newest addition of TEOS Theater and can embrace the shitty-on-purpose look and feel of a broadcast recording designed to look like a 37th generation copy—all blips, static, and tracking issues included.

Oct 11, 2021

JOHN CARPENTER'S HALLOWEEN SAFETY PSA

Sep 24, 2020

FOUR FROM HITCHCOCK

Throughout his career, Alfred Hitchcock directed 55 feature films, along with numerous shorts and documentaries. That’s not a bad haul, nor a bad legacy to leave behind to the world. Having said that, even the most ardent film fan couldn’t possibly name you half of his films in total. In fact, if you look at his filmography starting from the beginning, it would take you seventeen films before arriving at 1935’s The 39 Steps, really the first film, chronologically, that still enjoys discussion to this day. I’m not picking on Hitchcock, though – this is more just a reminder of the reality. Not a single director has a flawless track record when it comes to output (and if the names Christopher Nolan or Quentin Tarantino just flashed in your mind as a challenge to that, I’m laughing at you). But by now, Hitchcock has reached legendary status, and not just from the strong crop of films he left behind: there’s his larger than life persona as a morbid spokesman for his work; there’s his reputation for being a hard-nosed director unwilling to compromise his vision; and there’s also his penchant for victimizing his cast for reasons both professional and personal.

Because of his infamy, he’s achieved mythic status, and as such, we assume everything he touched shocked audiences, changed cinema, and left an indelible mark. Not quite. If you asked that same film fan from before to name ten Hitchcock films, undoubtedly these four titles would be among them: Rear Window, Vertigo, Psycho, and The Birds. They are sacrosanct, legendary, backbones of their respective genres, and sterling examples of a director fully in control of his talents and resources.

Photographer L.B. “Jeff” Jefferies (James Stewart) is in the

midst of recuperating from a broken ankle and is confined to a wheelchair in

his apartment. Sheer boredom leads him to watching his neighbors across his

apartment complex’s shared courtyard, keeping up to date on the various comings,

goings, and personal dramas unfolding in everyone’s tiny homes. It’s through

this passive observing that L.B. begins to suspect that one particular neighbor

across the way may have murdered his wife. With the assistance of his

“girlfriend” Lisa (Grace Kelly), who L.B. uses as a mobile quasi-avatar, they

investigate to see if L.B. really does live across the courtyard from a

murderer.

Like the other films in this set, Rear Window would inadvertently create an oft visited trope in

genre cinema going forward, either through presentation or in conception – in

this case, the idea of the voyeur, and of large open windows serving as movie

screens that depict the actions of those inside their own bubble, generally

unaware of their being watched…or sometimes being complicit in their

“performances.” John Carpenter would riff on this concept with a clever

reversal in his 1980 television movie Someone’sWatching Me! with Lauren Hutton and soon to be wife/ex-wife Adrienne

Barbeau. Australian filmmaker Richard Franklin, who would eventually helm the

extremely undervalued Psycho II,

would make a road-set homage with Road Games with Stacy Keach alongside a post-Halloween Jamie Lee Curtis (daughter of Psycho’s Janet Leigh). Finally, following his accident that left

him paralyzed and wheelchair-bound, Christopher Reeve would produce and star in

a Rear Window remake in the late

‘90s for ABC, with Daryl Hannah taking on the Grace Kelly role of the

adventurous troublemaker. It was…fine. Also like the other films in this set, Rear Window is one of many Hitchcock

films that sees a pretty blonde girl (Hitch’s fave) really going above and beyond to make an impotent or uninterested

man commit to her beyond mere petty flirtations and casual trysts. With L.B.

prone and imprisoned in his wheelchair, he’s powerless to stop Lisa as she

decides to take full control of the situation and break into the suspected

murderer’s apartment in order to validate L.B.’s beliefs – and this after the film opens with Lisa basically

nagging L.B. to marry her, which he declines with reasoning that makes the very

concept sound entirely objectionable despite the fact that he’s twenty years

older, has the physique of a snapped rubber band, and he’d be incredibly lucky

to have her.

A near-death experience leaves former police detective John

Ferguson (a returning Stewart) with acrophobia, a debilitating fear of heights,

and very retired. An old acquittance, Gavin Elster (Tom Helmore), hires him out

of the blue to follow his wife, Madeleine (Kim Novak), who believes that she’s

the reincarnation of another deceased woman named Carlotta. Being we’re in

Hitchcock territory, after Ferguson begins his reconnaissance, it doesn’t take

long for him to discover, whether or not Elster’s beliefs have any merit, that

he’s definitely not on a routine job. And he couldn’t possibly have anticipated

how obsessed with Madeleine he would become.

At 130 minutes, Vertigo

is one of Hitchcock’s longer features, and most of that running time is filled

with heavy exposition and twisting/turning developments that, at times, feel

almost more appropriate for a James Bond caper mixed with brooding noir.

Hitchcock once again reigns over his use of cinematography to deeply unsettle

his audience, using camera tricks and extreme points of view to take away our

balance and feeling of stability. The opening scene has Stewart’s Ferguson

hanging for dear life from the top of a very tall building as the gutter he’s

grasping slowly tears off the wall, and as a nearby officer reaches down to

help him, the poor schlub slips and plummets to his death – in just one

sequence, both Ferguson and the audience confront the ultimate fear: not just

impending death, but our front-row view of our only salvation being whisked

away.

Look, no one needs the plot breakdown of Psycho; considering it’s widely

considered Hitchcock’s crowning achievement as a director (these things are

subject to opinion, of course, but…it is),

Psycho is a masterclass in filmmaking

in just about every way – from expert casting (Martin Balsam!) to maximizing

low budget filmmaking (the crew was almost entirely comprised of Alfred Hitchcock Presents personnel) to

wrenching tension out of every scene through the use of slow-moving cinematography

and off-putting angles. Psycho should

be taught in film classes exclusively for its use of the camera. There’s the

slow opening push into Marion

and Sam’s hotel room window (which, while possibly

borrowed from 1955’s Dementia aka Daughter of Horror, is

still expertly crafted), and obviously there’s also that whole shower-scene thing, but

my favorite shot comes as the camera slowly pushes in on Norman standing by the

side of the swamp and listening in the dark as Sam calls out for him back at

the motel. It’s chilling and perfectly engineered. Honestly, I could go on and

on about the 1960 classic that inspired four sequels, a (failed) television

show, a remake, another successful

television show, the next generation of filmmakers (Brian De Palma, John

Carpenter, Richard Franklin, Brad Anderson), and a perpetual mark on the genre,

not to mention the permanent ruination of the sense of security one feels while

taking a shower in a motel room…but we all know this already. Adapted from the

novel of the same name by Robert Bloch, Hitchcock and screenwriter Joseph

Stefano improve the well written source material in every way. Stefano’s

screenplay changes Norman Bates from a monstrous killer to a sympathetic

figure, and Hitchcock had the forward-thinking idea of casting someone with

charming, boy-next-door features instead of someone who more closely matched

the unsightly, stocky, balding, and frustrated virgin present in the novel.

Even the shower scene is a complete rebuilding, in which Marion Crane’s demise

is limited to a few sentences: “Mary

started to scream, and then the curtains parted further and a hand appeared,

holding a butcher's knife. It was the knife that, a moment later, cut off her

scream. And her head.”

Loosely based on the 1952 short story by Daphne Du Maurier, Hitchcock’s adaption depicts a world being overtaken by angry hordes of birds, atypically flocking together in every species to wage an unexplained revenge against mankind – presumably for being the earth-raping assholes we always are. One of many folks caught in the swarm are Melanie (Tippi Hedren), who’s attempting to charm her way into the life of Mitch (Rod Taylor), who lives in an isolated coastal home. The attacks from the bloodthirsty birds increasingly mount until they find themselves trapped in Rod’s house and fending off the birds that manage to find their way in. Who will survive, and what will be pecked from them?

Truth be told, and in spite of its (deserved) reputation, The Birds is a mixed bag. As a youngin’

obsessed with JAWS and all the

animals-run-amok films that it introduced me to, I used to consider The Birds my favorite Hitchcock film,

but later viewings re-introduced me to a kind of silly film that’s actually at

its best when the birds aren’t on screen (school playground scene notwithstanding,

because that’s the kind of thing

Hitchcock did so well). However, once the opticals of marauding flocks are

overlain into the sky and birds both real and dummy are being thrown into Tippi

Hedren’s face, it all seems pretty nonsensical. It’s also hard to mentally dismiss

how much Hitchcock mistreated Hedren on set, which was the stuff of Hollywood legend

for years before HBO’s The Girl made

it mainstream knowledge in the earliest beginnings of the #MeToo movement.

Alfred Hitchcock is part of cinema history, taught in universities and film schools, still the subject of modern documentaries like the Psycho-deconstructing 78/52, and conjured in the modern descriptor “Hitchcockian.” The four films above are the top reasons why. Even if Hitchcock had directed four or four hundred films throughout his life, the merits alone of Rear Window, Vertigo, Psycho, and The Birds would’ve been more than enough to secure his legacy.

Aug 15, 2020

LAST SHIFT (2014)

The more learned viewer will definitely notice right off the bat that Last Shift is borrowing from John Carpenter's Assault on Precinct 13, but this time instead of a small band of cops and clerks taking on roving attacking gangs, it's just one rookie cop taking on the demons/ghosts/bloody secret history of the decommissioned police station of which she's in charge for its final shift. And it's not just thematically that director Anthony DiBlasi (Dread) is looking to Carpenter for inspiration, but also for the old-school approach.

Like Assault on Precinct 13, there are very few visual effects employed to scare the viewer; except for the minor use of green screen, nearly every gag is done with editing and camera tricks, and all of them work. There is no CGI on hand to offend the eye. And the cast is limited to just a handful of people, with most of Last Shift being a one-woman show (Juliana Harkavy).

Most importantly? Last Shift is seriously scary, falling back on another '70s concept beyond Carpenter and that specific era of cinema: the fear of encroaching satanism. The boogeyman and his followers featured in the flick are not Charles Manson and his Family, and are never called such (his name is John Michael Paymon, the surname being that of a demon most recently immortalized by another seriously scary flick, 2017's Hereditary), but at the same time, they are. The hallmarks are there: the long-haired, crazy-eyed, charismatic leader; the hippie chicks who follow him around; and his very disturbing agenda.

May 27, 2020

ESCAPE FROM L.A. (1996)

Dec 31, 2019

NEW YEAR'S WATCHING: ASSAULT ON PRECINCT 13 (2005)

Dec 25, 2019

Dec 12, 2019

MIDNIGHT SPECIAL (2016)